By Dr. Gene Lindsey

Members of the Massachusetts Society and Guests,

Throughout a career of more than forty years I have had the mindset of a guild craftsman as I have worked in the office, in the emergency room, and at the bedside in the hospital. That is the case despite my title today which is President and CEO of Atrius Health and Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates. The truth is that my sense of identity is that of a practicing physician who through some strange sequence of events became a healthcare executive late in a very professionally satisfying career.

I think that many physicians, trained in the style of apprentices as we moved through medical school and our internships and residencies, also share the mindset of the guild craftsmen. Based on the description in Wikipedia, the guilds that arose in Europe deserve some of the credit for moving civilization from the Dark Ages into the age of enlightenment, science and industry. These associations helped the establishment of universities. Quite remarkably, the Barbers guild established in 1308 evolved into the Royal College of Surgeons in 1800. Those guild craftsmen were not only great artisans who loved their crafts and shared secrets of their trades with apprentices and one another, but they were also pillars of their communities and were fierce defenders of their independence.

That description of guilds also fits the way that medicine has been experienced by many of us and our patients in the not too distant past. We speak fondly of the art and craft of the practice of medicine and love to reminisce about the days when our clinical skills were truly appreciated. When I think of those days, I think about why I became a physician and my role model, Dr. Edwin Masters. Dr. Masters embodied all that we see in a Norman Rockwell painting of the kindly old doctor who manifests the attributes of a craftsman.

During my senior season of football in high school I was under a lot of self-imposed pressure to play well enough to attract the attention of college recruiters and maintain the sort of academic credentials that would be compatible with my dream of eventually going to medical school. The team was not having a great season and I became quite ill with a severe sore throat. By the time I saw my general practitioner, I was feeling much better and had every expectation of playing in the Friday night game. I was floored when he said that he was admitting me to the hospital because of hypertension. I had no understanding of why it was happening and was terrified about what it meant. It was an awful experience except for the appearance of Dr. Masters.

Dr. Masters was a grandfatherly physician who was a quiet but steady presence in my community. I had never been to his office which later I discovered was in a little house on one of the busy streets near my home. I knew him because he taught Sunday school at my church. Somehow I knew that he had been trained at Vanderbilt and was an esteemed member of our community. He came into my room and explained why my doctor had admitted me and proceeded to reassure me that he understood how important it was for me to get back to my team and my plans. It was too late for the game that week, but he assured me that I would play the next week no matter what the tests showed. Over the remainder of that year I would occasionally see him at his office. I waited in the parlor, was examined in what had been a bedroom, had blood drawn and an EKG done in the kitchen, and saw his secretary in the dining room where she managed the practice and gave me my next appointment.

13 years after Dr. Masters had sat at my bedside, I began to practice medicine in the new environment that Dr. Ebert had created at HCHP. My family kept asking me when I was going to start my “own practice” but I realized that time and events had forever made the sort of solo practice that old Dr. Masters had a fading memory for me. I think we reminisce about grand old clinicians like Dr. Masters because they embodied the skills that we as physicians value most: solving problems for patients with our critical thinking, powerful reciprocal relationships with patients, and the opportunity to use the clinical skills that we worked so hard to obtain to the benefit of those who trust us. When our marketing department surveys patients about what quality means to them, the patients do not answer with HEDIS measures. Instead they are looking for a doctor who listens and communicates. Dr. Masters lived in a world of guild medicine and he was a master of listening and communicating. In memory today he provides a picture of what so many patients are still looking to find in combination with the high tech and science of our current medical industrial environment.

Medicine is rapidly morphing from being a guild-like activity to an activity embedded in an enterprise. The enterprise is necessary to handle the complexity and the capital needs of today’s medicine. Yet many of us have our hearts trapped in the model of the craftsman. We daily express our desire to be free and independent of onerous regulation and administrators who lack personal understanding of the difficulty of working under the scrutiny of the rules of politicians and the threat of the plaintiff’s bar. Our independence is threatened on the one side by hospitals that want to control us to serve their objectives and on the other side by investors and agents of other business interests who see healthcare as a great opportunity if they can control the flow of patients by controlling the doctors. In other words one could say that we are a guild under siege.

I posit that we can be true to our best intentions and exercise the best of our guild values while our craft becomes part of an enterprise that is beginning to be known as an Accountable Care Organization. I want to share with you my observations and reflections about what strategies have worked for Atrius Health in a time of change and what we have learned from what did not work so well for us.

Let me start by introducing you to Atrius Health.

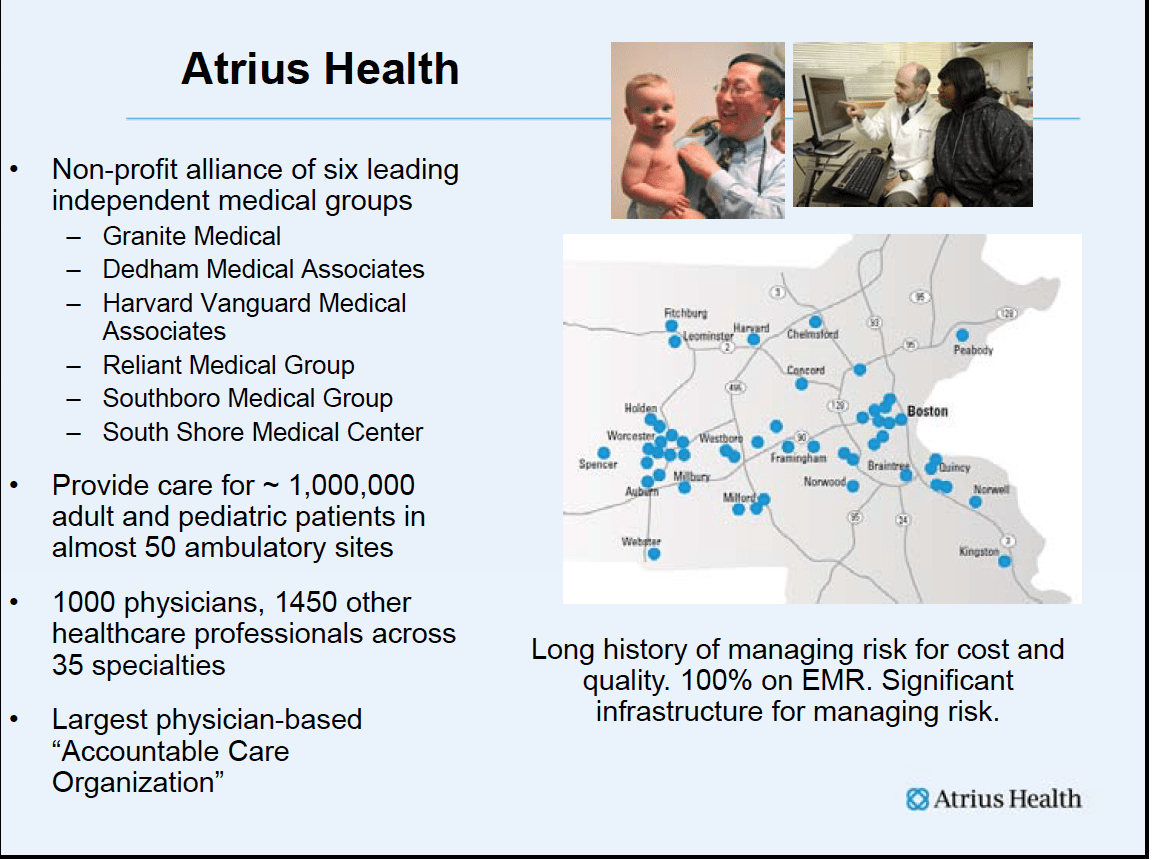

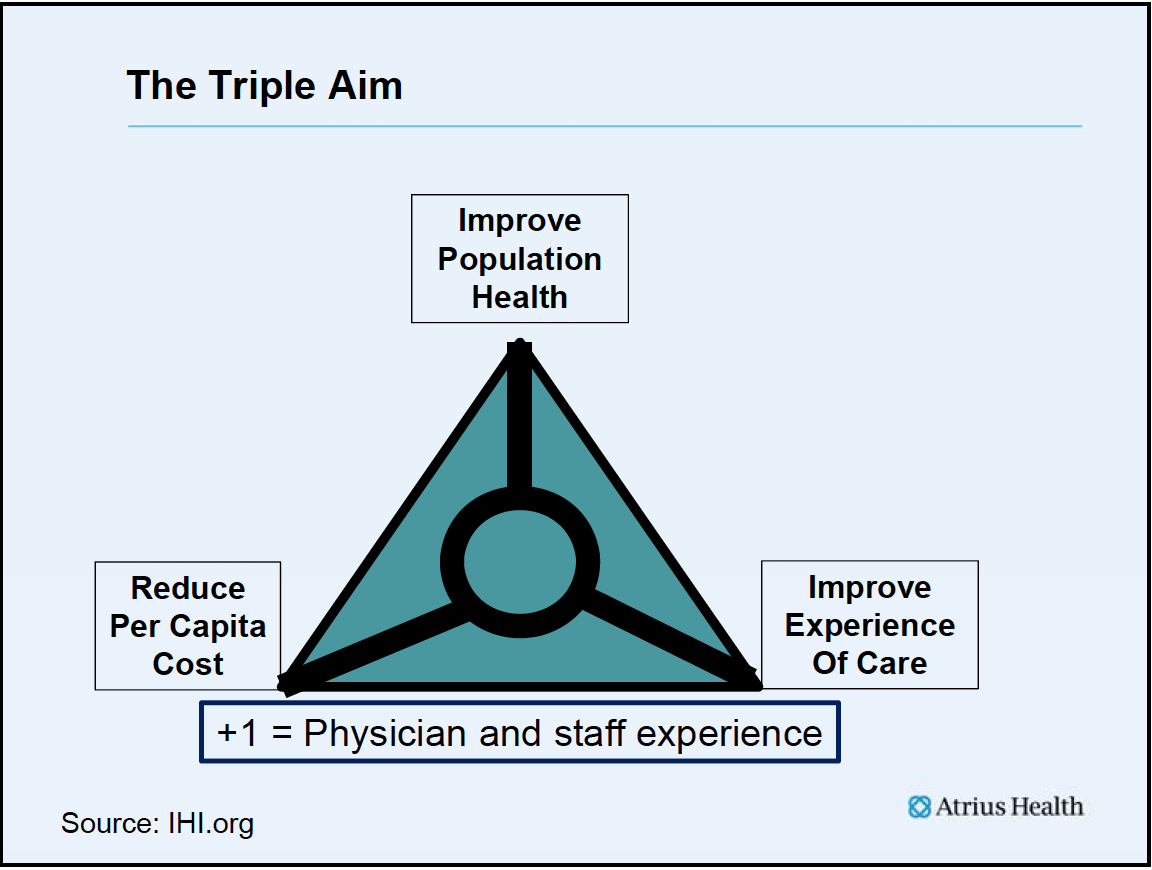

We are an organization that is continuing to evolve towards a more integrated system of care, and we are comprised of six multi-specialty ambulatory group practices that work together towards the goals of the triple aim – improving experience of care, improving population health, and decreasing the cost per capita of healthcare. To those three goals we add a “plus one” goal that is improving the experience of practice for our physicians and staff. The Atrius Health groups are often held up as an example of an Accountable Care Organization because we began the move from guild to enterprise so much earlier than many of the other physician practices in the Commonwealth.

The largest medical group in Atrius Health is Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, the legacy practice of the staff model HMO of Harvard Community Health Plan. Dr. Robert Ebert, then Dean of the Harvard Medical School, was our founder. After struggling for several years to get funding, and working against the resistance of many and with the help of a few key people like George Thorne and Howard Hyatt who understood his dream, Dr. Ebert launched the Harvard Community Health Plan practice in 1969 with 88 patients. That was a time of transition much like this time. Dr. Ebert and other thought leaders were as concerned about the future of medicine in those early days after the passage of Medicare and Medicaid just as we are now working against uncertainty in the aftermath of Massachusetts Chapters 58, 305, 288 and 224 and the national Affordable Care Act.

Dr. Ebert was an early proponent of the advantages of population-based healthcare and believed in the value of preventive care and health maintenance. He was quite familiar with Kaiser and was interested in how their concept might be expanded with his relationship with HMS to become a “teaching practice”. He wrote and spoke extensively about how his era was not training young physicians to practice in the ambulatory environment where he believed the future would be focused if we were ever to improve the health of the public.

Dr. Ebert had “triple aim thinking” 40 years before it was described as a concept by Tom Nolan and others in 2007 at IHI. Dr. Ebert dreamed of a prepaid, ambulatory, multispecialty group practice focused in the community that could meet many of the needs of the patient under one roof. The practice in his vision would be somewhat like a hospital, but different than the outpatient department of a hospital or the average community doctor’s practice. In this new environment, medical students, interns and residents could be taught the art and science of medicine in the patient’s world, focusing as much on the patient as the patient’s disease. He was constantly trying to substitute prevention for treatment of chronically neglected problems.

In his thinking about this new type of practice, Dr. Ebert was not planning to abandon the guild values of the profession. Rather, he hoped that a new environment of patient-centered prevention would eventually replace much of the environment of the hospital. He believed that much of what he saw as dangerous and misdirected in the healthcare of his day was a derivative of the system of fee for service finance. He talked from the perspective of a scientist and hospital specialist who was disappointed that the world in which he lived and worked was misaligned with the results he believed were possible and needed.

Dr. Ebert recognized much earlier than most of his contemporaries that, despite great science and exploding technology, something was missing from the application of these technologies to the patient. He understood the tension between volume and value long before many of our current practitioners were born. Because Dr. Ebert understood the undermining power of waste, he wanted to start a practice that could only be financed by finding cost efficiencies while still delivering more and better care for less money. HCHP practiced team-based care with nurse practitioners and an electronic medical record from the first day it opened its doors.

I began my medical studies at Dr. Ebert’s medical school in September 1967. The following month, Dr. Ebert gave a speech about the future of healthcare at neighboring Simmons College. In that speech he said:

“The existing deficiencies in health care cannot be corrected simply by supplying more personnel, more facilities and more money. These problems can only be solved by organizing the personnel, facilities and financing into a conceptual framework and operating system that will provide optimally for the health needs of the population.”

Harvard Vanguard is not only Atrius practice with a history that is rooted in the tradition and values of patient centered practice with elements of a guild like past. The second largest affiliate of Atrius Health is Reliant Medical Group which is the legacy practice of the Fallon Clinic with an even longer history of practice innovation with guild-like roots than does Harvard Vanguard. Dr. John Fallon brought a team of physicians from the Mayo Clinic to Worcester in 1929 to create the first group practice in Central Massachusetts. The other four groups of Atrius Health all have deep roots in the environment of private practice, combined with strong experience in managed care. South Shore Medical Center opened 50 years ago, Southboro Medical Group 60 years ago, and Dedham Medical Associates 75 years ago.

Our smallest group is Granite Medical Group in Quincy. Its history may be more typical of the path that many physicians are taking today. Its founder and President, Dr. Guy Spinelli, opened his practice fresh out of training in 1982 in a small office in a house working solo with his mother as his only staff. He acquired a partner. He and his partner then created a small primary care group practice which then later affiliated with a strong group of medical specialists to form Granite Medical Group which then joined Atrius Health.

It is astounding that in one physician’s practice lifetime, Dr. Spinelli completed the transition from a cottage environment with true guild-like sensibilities to an environment that is perhaps or soon will be Big Med and he has still preserved the same values. In preparation for this presentation, I asked Guy what was on his mind with each step in his movement from solo practice to the enterprise level of practice. His answer was that each move was driven by what he thought was best for his patients and his community. He was always asking himself how he could offer more to the patients who depended on his judgment.

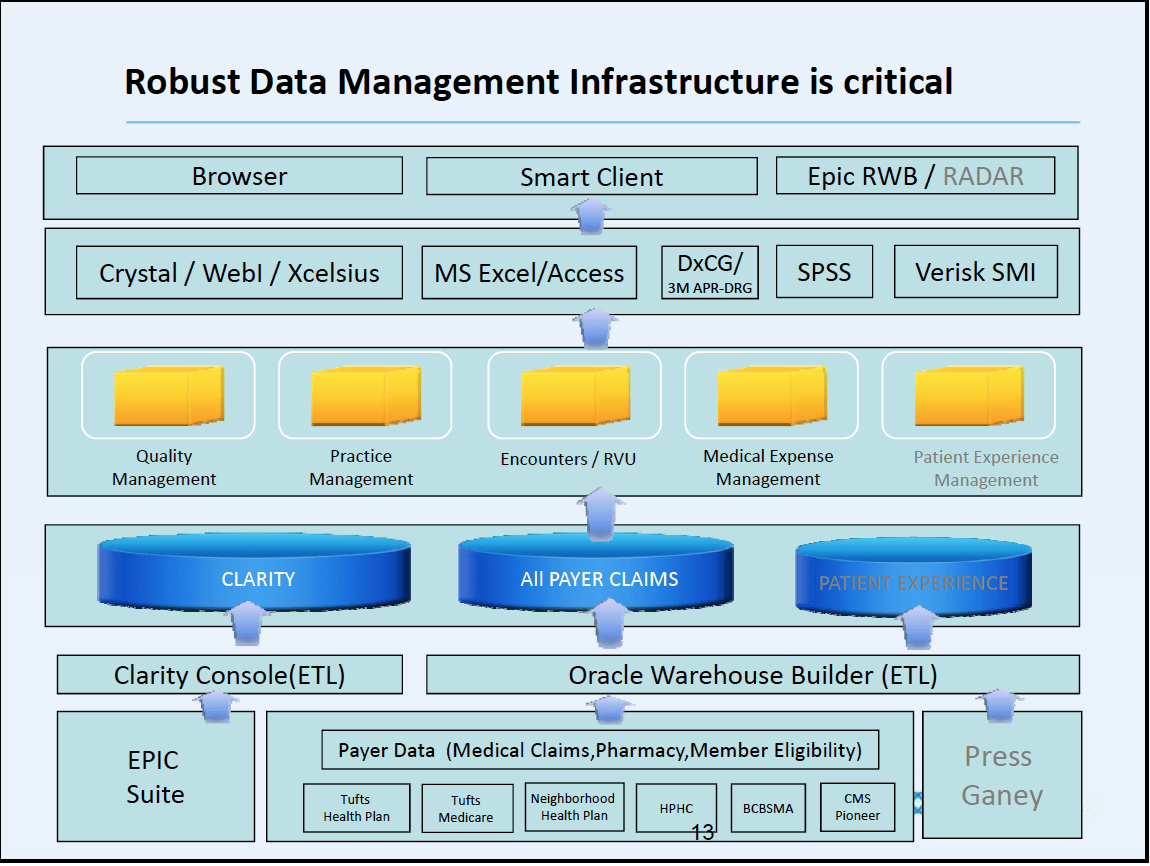

Today there are over one thousand physicians employed by Atrius Health affiliates to work with more than 1500 other licensed health care professionals and 5000 other professionals in an enterprise that provides about 3.5 million ambulatory visits a year to one million citizens of Massachusetts. About half of our physicians work in primary care. We work with about 18 preferred hospitals. Atrius Health groups offer patients 50 sites across Central and Eastern Massachusetts where they can get care that is designed to make it easier to be healthy close to home. We have long been known for our quality. Our annual revenues are in excess of 2 billion dollars a year. The physicians and other professionals at Atrius Health groups use the most sophisticated IT infrastructure and big data resources that are available. They are supported by clinical pharmacy, care managers, overnight telecommunications staffed with advanced practice clinicians, and weekend urgent care. We have partnered closely with VNA Care Network and Hospice to enable more than 500 nurses to bring their in-home care skills together with the Atrius Health groups to create the possibility of even more innovation as we seek to make it easier for our patients to enjoy good health.

In a recent article by Dr. Atul Gawande in The New Yorker called “Big Med”, he compared the evolution of restaurants from small local establishments to large chains of very efficient restaurants like the Cheesecake Factory to the evolution that we are seeing in healthcare. It was a comparison that gave many indigestion, but there was much to chew on in his metaphor. He wrote at length about the pride that each chef took in what he or she was able to create in a system that had standard work and a common menu. Gawande’s definition of Big Med hit close to home because two of our local iterations of Big Med, Steward Healthcare and Partners Healthcare, were showcased in the article. Dr. Gawande said,

Today some ninety “super-regional” health-care systems have formed across the country—large, growing chains of clinics, hospitals, and home care agencies. Most are not for profit. Financial analysts expect the successful ones to drive independent medical centers out of existence in much of the country—either by buying them up or drawing away their patients with better quality and cost controls. Some small clinics and hospitals will undoubtedly remain successful, perhaps catering to the luxury end of health care the way gourmet restaurants do for food. But analysts expect that most of us will gravitate to the big systems just as we have moved away from small pharmacies to CVS and Walmart.

As I have thought about the article, I have asked myself: “Would I want to practice in a “Cheesecake” environment even if it was efficient and effective?” I reflected on the effort that our management team has invested over the last five years as it has tried to lead our practices toward the triple aim by throwing an avalanche of new programs and initiatives at our clinicians.

Over 5 years ago Atrius Health anticipated the fact that the year over year increases in revenue that were necessary to support our practice would end someday. On revenues of almost $2 billion a year, a drop of 5% in one year would produce a sudden $100 million deficit. We could imagine such a fall if the revenue increase dropped from 8% to 3%. Many of our groups had survived a 30% loss of revenue in 1999-2001 when Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare went into receivership. It was hard to maintain quality in the midst of such a crisis. We burned the furniture to get through that winter and we did not want to do it again.

Our 2008 strategic plan included an effort to support the movement to global payment since we felt it was easier in that environment to create programs that lowered the cost of care. Our data showed that there were some potential hospital partners who could give our patients equal quality for a lower cost. Conversations with those hospitals convinced us that they saw the same compelling reasons for change that we saw and that encouraged us to move business to them since we buy significant specialty and hospital support.

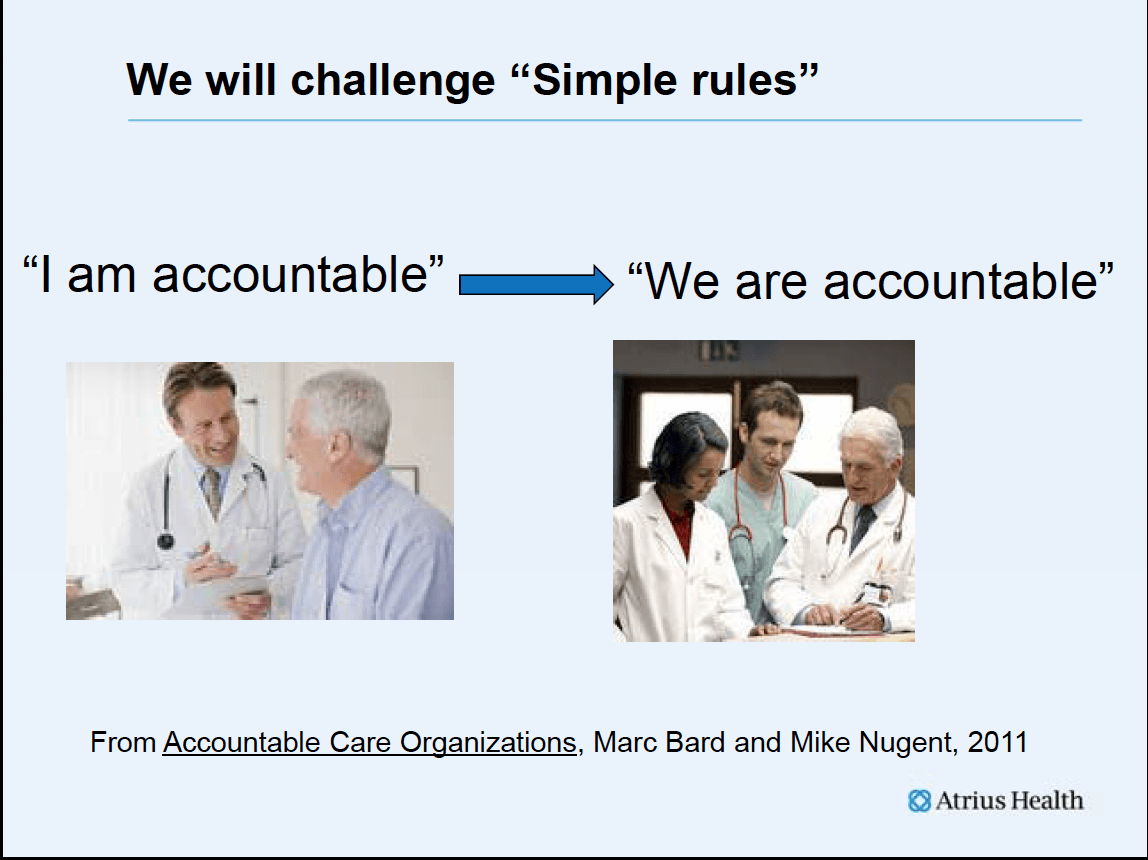

We decided to invest resources in a leadership academy and improved data systems. We tried to broker conversations with others in the market about forming relationships that would be cooperative and better support the community. We supported team based care, and I began to speak about the need to move from “I am accountable” to “we are accountable”. All of our practices became Level 3 NCQA certified patient medical homes, but we still continue to refine the model. We recognized that some of our patients thought our technical quality was better than our service excellence, so we talked with institutions whose patients scored their service as superior to ours and then hired the same consultants to help us improve our service.

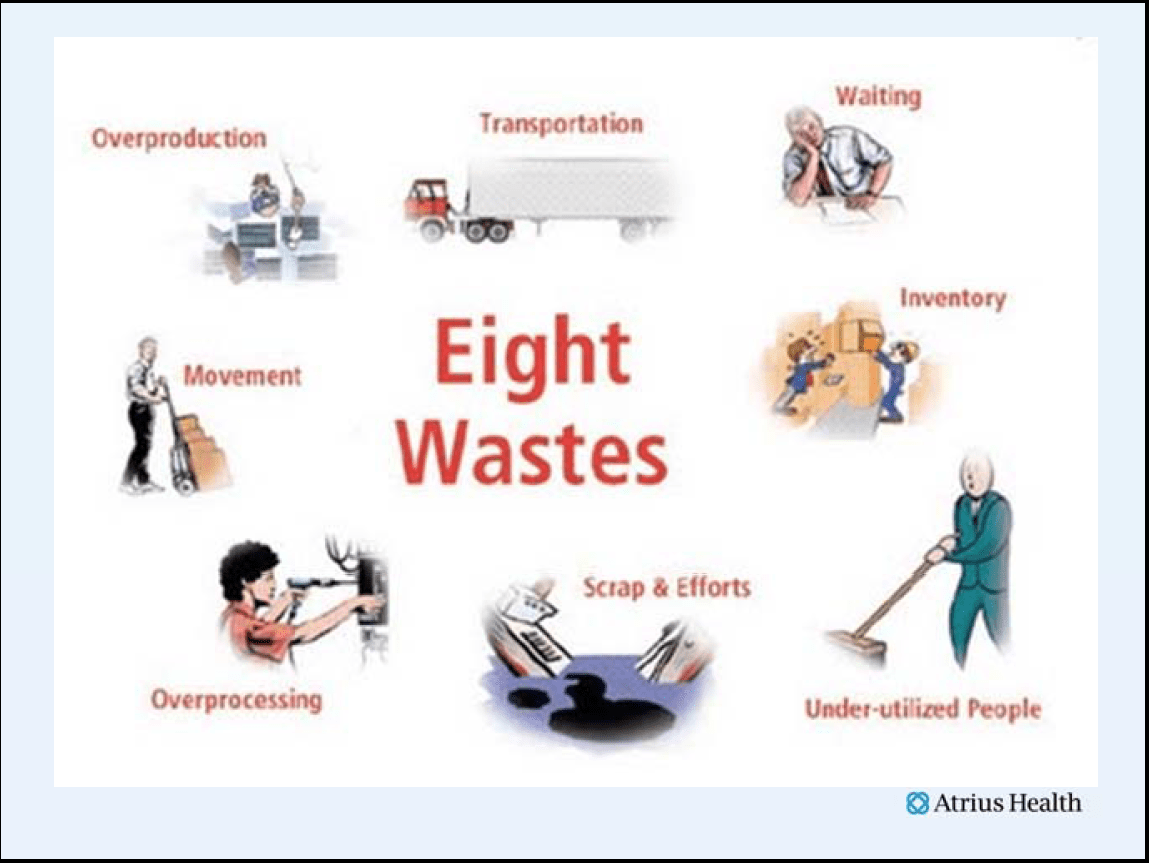

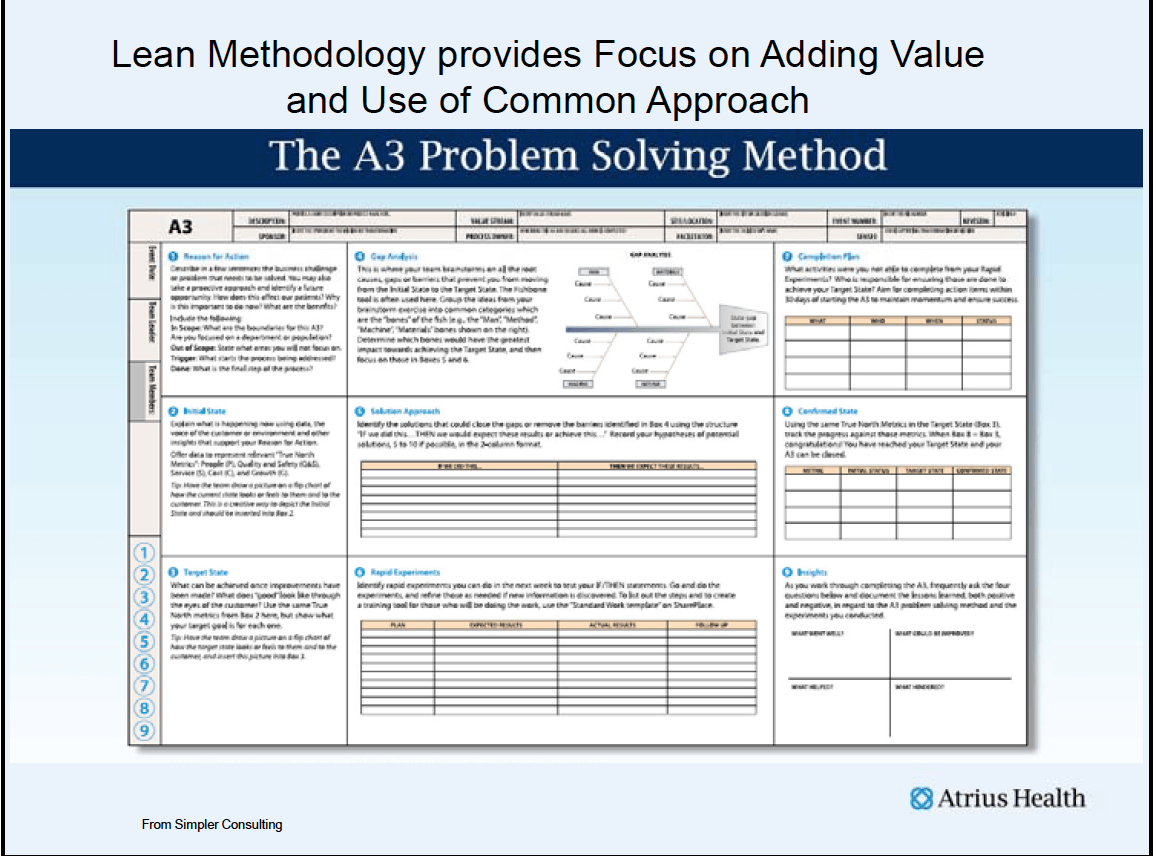

Our biggest investment decision was to embrace the huge task of giving a workforce of over 7000 people skills in Lean methodology for eliminating waste in our processes and increasing respect for the people who actually do the work. We had been impressed that Lean had enabled Virginia Mason Medical Center and Group Health in Seattle, ThedaCare in Appleton, Wisconsin and Denver Health to become better at getting better. The process was described as a long journey that required great change. We decided to try. We focused on respect and recognizing and eliminating waste.

We tried to define value in the context of the patient. We created standard work and instituted management for daily improvement. The goal was to develop processes where every step adds value and where all of the mundane and routine things are handled through consistent processes so that extra time can be dedicated to physicians thinking about the needs of their patients, both in the office and in a proactive way.

Finally we accepted help from friends. Blue Cross supported innovation with a grant that was coupled with executive education and then produced a new payment mechanism called the Alternative Quality Contract that gave us a reason for action and resources for change. We challenged ourselves to learn about shared savings programs and invested in care models to be successful in the ACO environment, becoming one of 32 Medicare Pioneer ACOs in the nation last year.

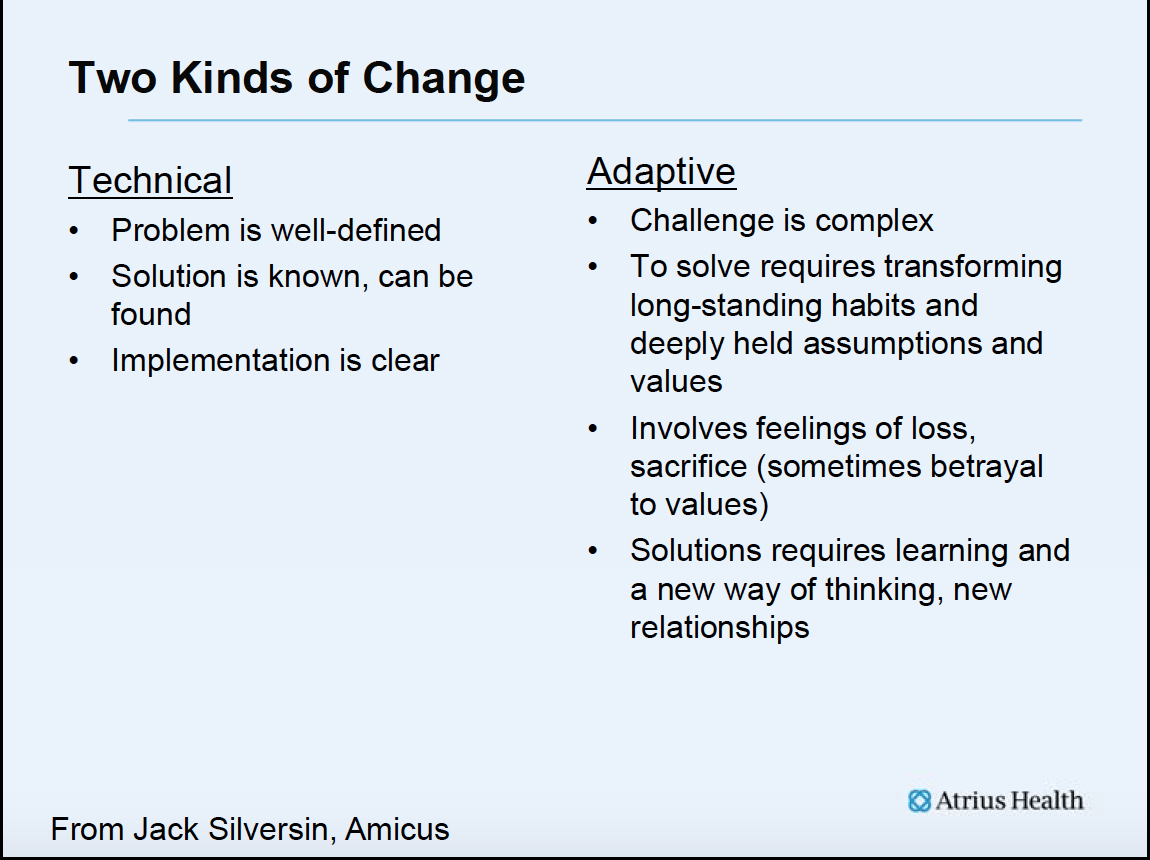

Some of this investment has worked out very well and we have put in place many of the assets that will be necessary to succeed in a world of mostly global payment. I will borrow from Ronald Heifetz and call this part of our strategy the technical change. With technical change the problems are well-defined, the solution is known or can be found easily, and the work that needs to be done for implementation is clear. Much of the technical change that we challenged ourselves to initiate because it would be of benefit in a new world we have been able to accomplish. For example, as the result of our work we moved our tertiary care to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and moved more care to community hospitals. We have significantly improved our AQC quality scores each year. The lessons learned as we improved the quality scores in the AQC have been valuable as we are now in the Pioneer ACO where access to shared savings are available only if quality is acceptable and downside risk is mitigated by improving quality. We are beginning to see improvement in our patient experience scores.

The most significant return has been in Lean. We have several thousand employees across all groups of employees who have robust Lean vocabularies. They are coming together daily in their units to plan the work of the day, share what is working, discuss and solve problems and improve the flow of their shared work. Lean has been core to the continuing improvement of our evolving advanced medical home concepts. We have used Lean to solve problems between different departments, design new facilities, create common specialty services between Atrius Health partners, and between Atrius Health and hospital partners. Some of our greatest gains have been improvements through Lean work at the front desk, in the pharmacy, and in our Harvard Vanguard Lab. Tracking the ROI on Lean is very difficult because so much of it becomes just the way that we work, but there is no doubt that the investment has been returned by several multiples. Perhaps the greatest benefit of Lean has been the engagement of our workforce and management in a new type of empowered partnership.

Our data warehouse capabilities have been an enormous asset as we work with hospital partners, payers, and plan programs and services.

We are able to track utilization to individual clinicians and are developing the skills that will enable us to improve practice variation and follow utilization of lab and consultative services. We can now do meaningful analyses of our high risk patients. We have scorecards to measure our relationships with health plans and with hospitals so that we can improve together. We can analyze variation in practice patterns, share best practices, and see both improvement and decreases in variation.

Here is an example:

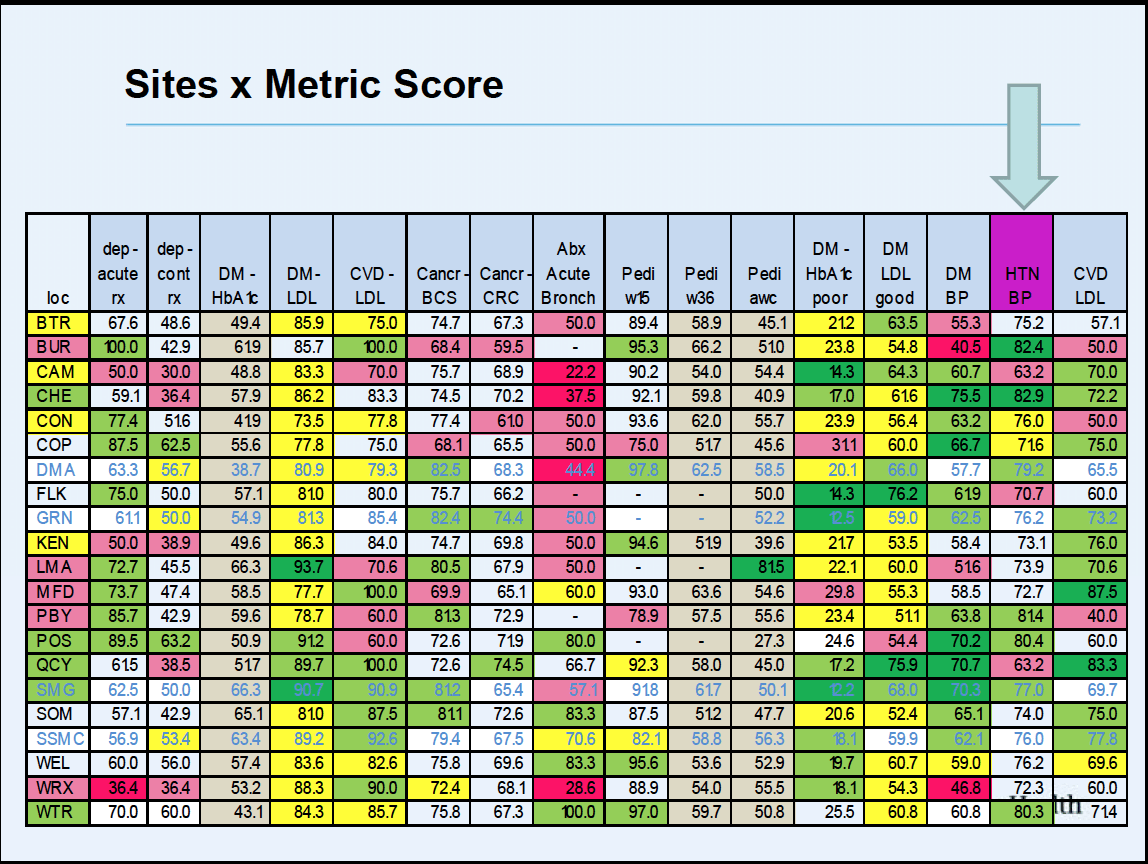

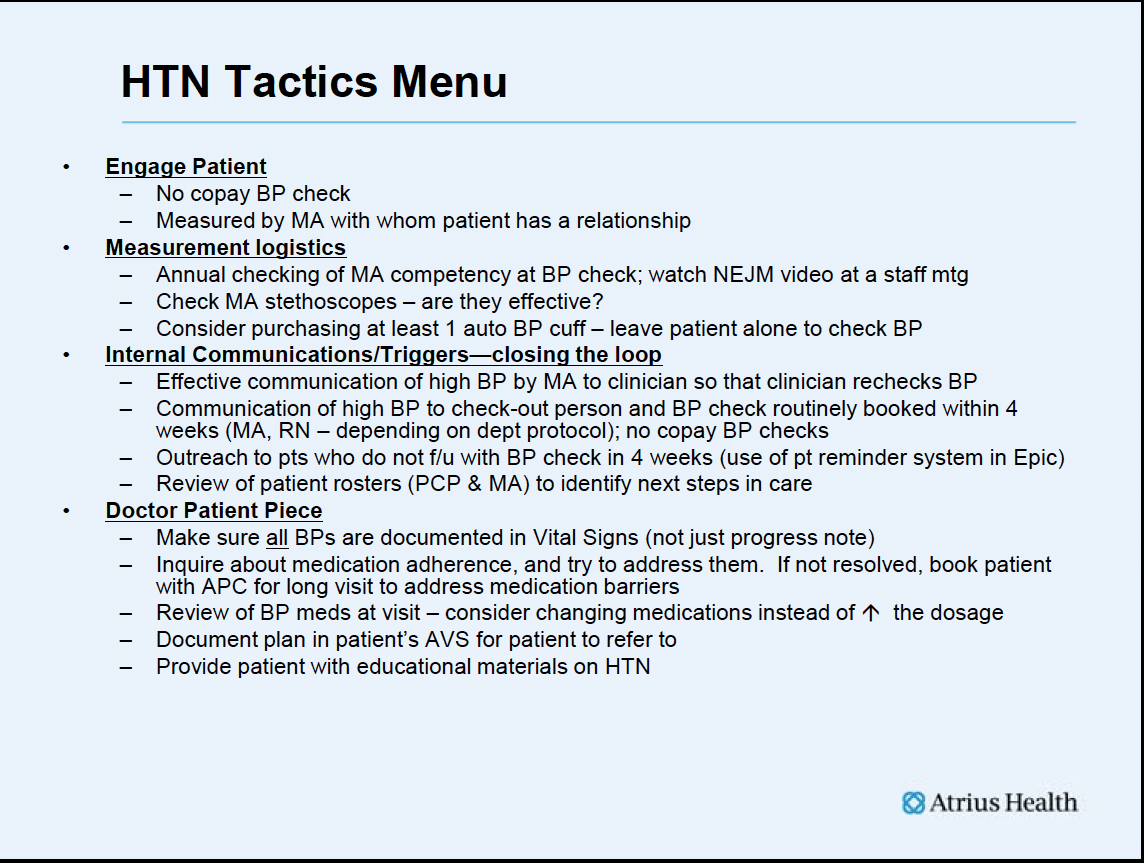

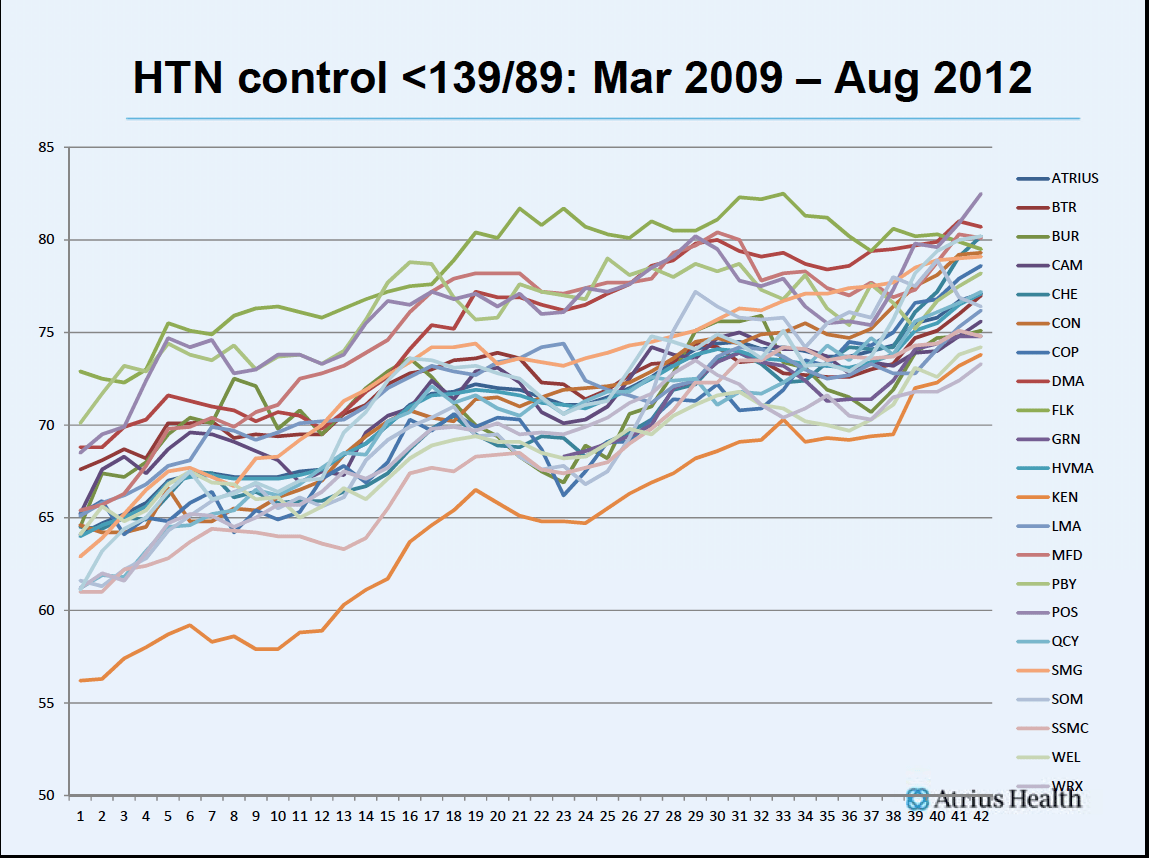

We look at each of our sites and grade them as red, yellow, green for performance. If you look at the column for hypertension, you can see how the sites are faring. This allows us to find those who are doing the best and then to determine what they are doing.

By sharing this information with other practices, all of our practices improve as does the variation in their quality.

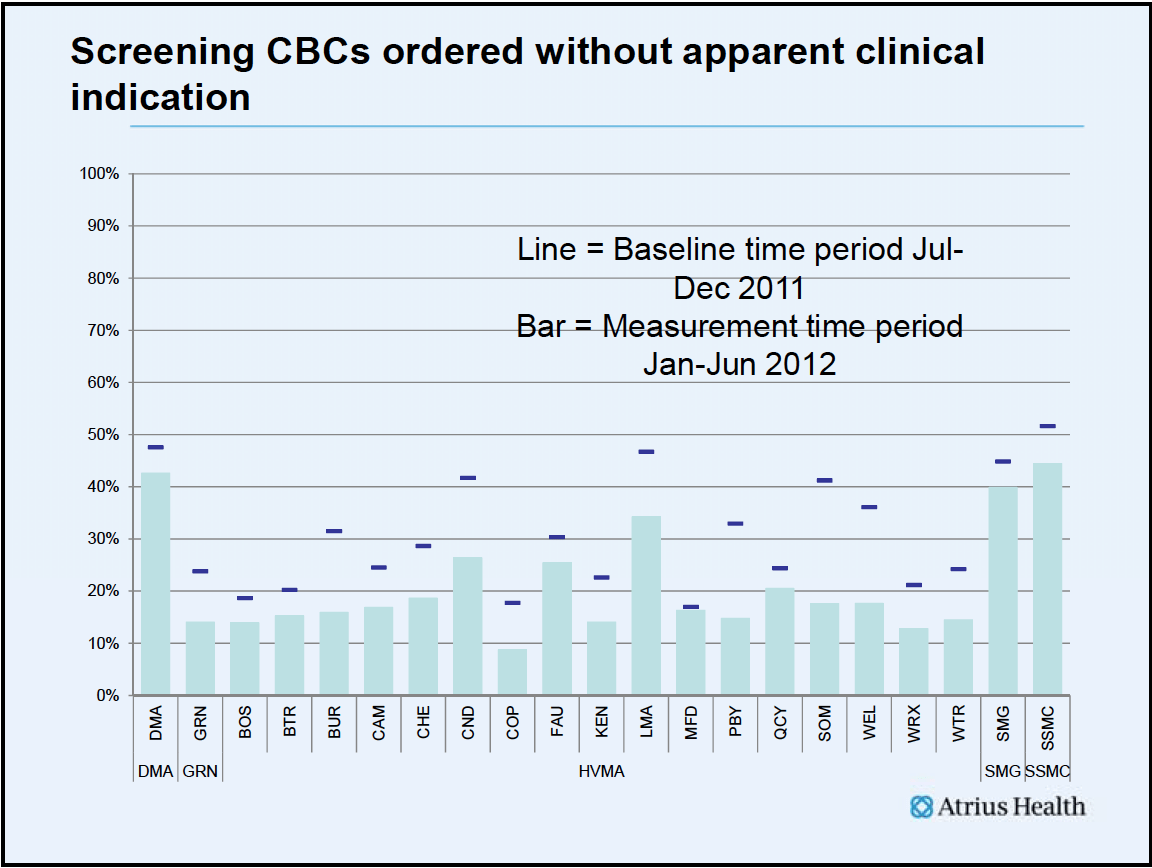

In another example, we find those who are ordering tests that are not clinically relevant and give them that feedback.

Variation is the enemy, and it is the physicians who must determine what constitutes best practice for them and their colleagues. We are working through a long list of conditions.

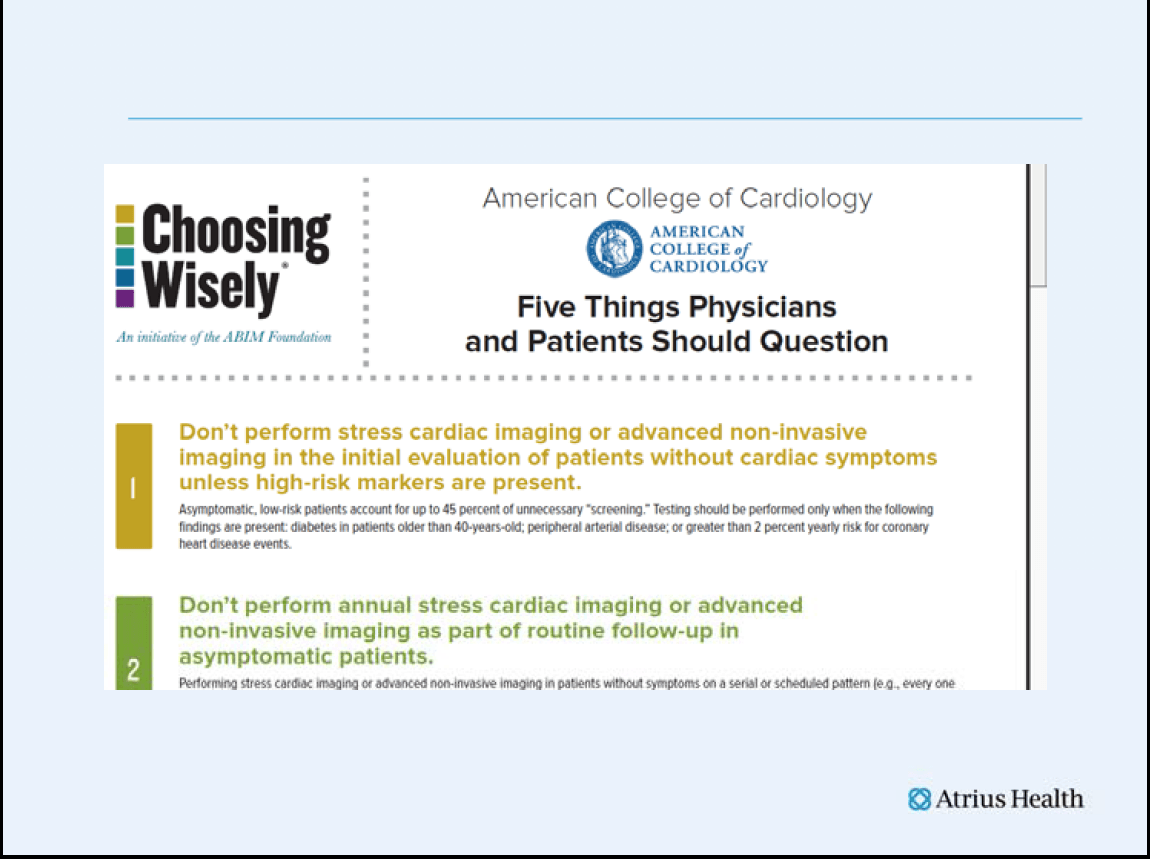

ABIM has adopted this same technical change process. They have asked each of the medical societies to select 5 practices that should be eliminated.

The thought is that knowledge is power, and just knowing what is wrong will change practice. Yet we know how often that is not the case in medicine. Even when we have good data, our guild mentality produces huge and often unjustifiable variation in practice. We experienced this when we developed standard work for our patients with diabetes. There was a need for a common definition – we had to pick from A1C or fasting glucose. We needed agreement about the order in which one would try different medications in the absence of clinical signs to try something else. We had to get agreement from almost 200 internists at Harvard Vanguard about the frequency of follow-up visits and the screening and health education needs of these patients. We made great progress, but we are not where our patients need us to be.

We are measured on our ability to improve these patients’ health outcomes, yet we know that our ability to ensure that patients receive all recommended screening is far less than 100% and although outcomes have improved there is more work and more to learn before the result we want matches what we have accomplished.

As we went through all of these technical changes, we began to realize that we were not moving as efficiently towards our goal. We looked to the experience of other organizations like Virginia Mason and Thedacare and realized that they had used a social compact to resolve some of the tensions of adaptive change. We spent a year at Harvard Vanguard creating such a social compact with our physicians which we envision as a continuing process that we will spread.

It is difficult for me to imagine where we might be if we had not looked into the future and prepared as we have. I know that we would be in a very different place. Are we where we want to be? No. Despite all of these investments and information, we have not been able to progress as far or as fast as we had hoped. Perhaps partial success has been an impediment to progress. It is hard to work to avoid a crisis when you are doing well in the present. I am sure that some of our physicians and staff have thought that the predicted difficult times would never happen, but our projections suggest that expenses would eventually grow faster than revenue and that could happen in 2013 or 2014 if we do not accelerate our rate of improvement. To continue without even more improvement is a recipe for disaster. With the early start we hope to push down our TME faster than reimbursement falls, but we will have to pick up the pace of improvement or be forced to take actions in the form of cuts that we had hoped to avoid.

What could be better? I do not sense that the work lives and satisfaction of our physicians have improved as much as we had hoped. Their energy is the rate limiting factor in our progress. They are still spending an enormous amount of time doing tasks that are not “top of license activities.” The process of “standard work” for doctors is far from complete. As a result, many do not share the enthusiasm for Lean that you find in the work of many of our other employees. I sense that there are many who continue to struggle with increasing work-life balance issues and who are experiencing the continuing pain of adaptive change.

Lean thinking is built on the same concepts as the scientific method and its success is predicated on demonstrating improvement with appropriate measurement. Many times the postulated solutions that arise in the Lean process fail to generate the target results. When that happens we rethink the solutions and develop countermeasures. This process almost always generates new insights and subsequently the results improve. At this juncture we only have theories about how to get better in this area of improving physician life, but we believe the most likely solution lies in the improved performance of management and developing even better “standard work” for everyone including our physicians. Everyone on the team needs to better understand and better fulfill their particular role in the care model.

In Lean management better performance and accountability is associated with coaching, mentoring and teaching. Recently we have added more site based medical leadership to support these activities. During this last year we also freed up more time for our internists to do practice management and participate in management for daily improvement activities. I am convinced that improving the experience of practice remains the greatest challenge that faces us all. And I know that new physicians think that our practices are rich in the supports that were not available to them where they practiced before so we are far from alone. Despite the richness and elegance of our assets, the fact that the experience of practice has not improved as much as I had hoped it would is my greatest continuing concern.

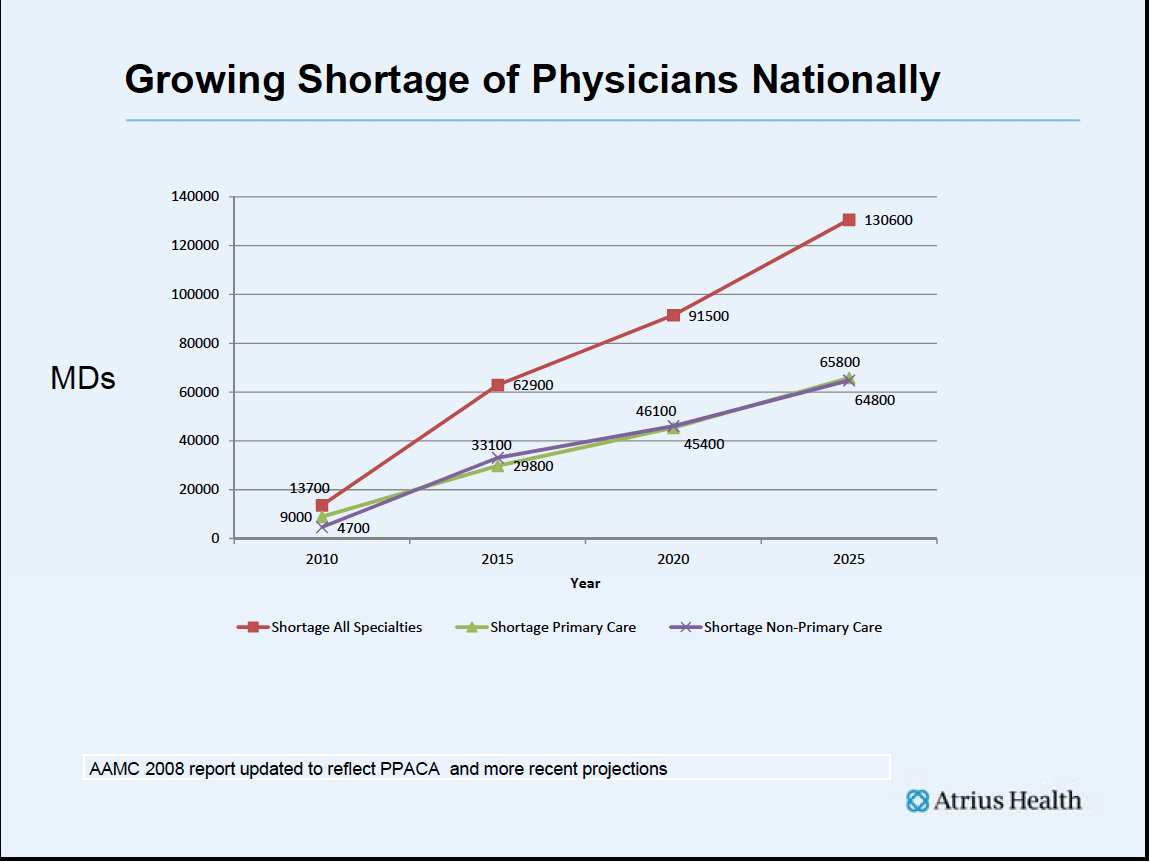

New problems are on the horizon. Because of the demographics of practice, with many of PCPs retiring at the same time that we have a grey tsunami of baby boomer patients, our greatest challenges as a profession lie in the proximate future. I fear that, even before we evolve the ability to manage our current loss of resources, that we will have a much greater problem; there will not be enough physicians to continue the current care delivery model.

As a physician, I have known better days. The last decade has been increasingly difficult for physicians. The statistics suggest that any increases in physician income are the result of working harder. It is getting harder to work harder. The result has been less time with patients and less time for critical thinking. There is some reality to this cartoon.

I fear that one of the things that we have not successfully transferred to Big Med is enough time with our patients and the time to ponder their problems. I think it is ironic that we now are attempting to improve utilization of scarce resources with a program called “Choosing Wisely”. I heartily and enthusiastically support the program, but find it ironic that perhaps the reason that we don’t choose wisely is that we don’t have the time to think wisely and to counsel our patients. Instead, we substitute a few key strokes to order a test on our computer, hoping that the answer to the clinical problem will pop up in the “results inbox” because we do not have time to think wisely or consult the literature even though that is on-line now also.

Recently I had the wonderful opportunity to spend an afternoon with Clay Christensen at Harvard Business School. He invited the leaders of all of the Massachusetts Pioneer ACOs to come in and talk with him and Dean Flier from Harvard Medical School. Four of us were able to make it. He was interested in ACOs as a disruptive innovation. He asked a question which you can easily find in his writings, “What does your customer hire you to do?”

Being somewhat literal in nature, I said, “It depends on what is wrong with the patient.” As the words came out of my mouth, I realized that I had missed the point. It is true that pregnant mothers hire you to deliver their babies, and people with broken bones want them set. Elderly patients with swollen ankles who are short of breath want those problems resolved and you can hand them a script for furosemide. But, universally, the job our patients hire us to do is to care about them and to listen to their concerns, and to think about them long enough to help them solve their problems efficiently and effectively. This kind of care is hard to deliver in a 15 minute appointment. A great use of all of our new Big Med tools would be to restore to us what a few of us can now barely remember; time to listen and think. I do not think that most physicians have given up caring, but I do think it has been a long time since many of us have had the time to do what we learned to do. The shame of it all is that if you have graduated from medical school in the last fifteen years you may have never had the experience of practice in any environment other than the enormous demands of practice as we now experience it.

I can testify from my own experience that as physicians are pushed into Big Med enterprises, there will be substantial pain associated with the loss of autonomy, the sense of entitlement and the protections that we have been able to craft for ourselves in our guild like environment. Ronald Heifetz calls this reality the pain of adaptive change.

He says that adaptive change is characterized by complex challenges and that tremendous stress is felt by the affected individuals. Such changes require transforming long-standing habits and deeply held assumptions and values. Solving problems of adaptive change almost always require learning and a new way of thinking, and the development of new relationships.

I have come to believe that the real antidote to that pain of adaptive change lies in the preserving the patient centered values of our old guild-like days. The antidote to the pain lies in intense devotion to the patient, the opportunity to apply our critical thinking, and the sense of professional unity in the face of challenges we have responded to as a profession. The challenge is to see the extension of our old proven values in these new contemporary forms of practice and carve out the opportunity and time by effectively improving our models of practice. The transition can be difficult to do when you are talking about standard work and the physicians are fatigued and realizing loss and are thinking only that they will lose more of their ability to take care of individual patients or to apply their ability to think. We must use all that was great about working in a guild, combined with today’s science and the organizational structures of Big Med to ensure a better future for all of our patients.

In retrospect, back in 2008 Atrius Health management approached the changes necessary for the future as if they were technical change. We thought solutions would emerge from reasoning and logic and it would be a matter of “Just do it”. As much as I valued our guild heritage, I did not realize that the future did not require leaving the guild behind. Rather it requires moving guild thinking and the associated values of our relationships with our patients and our ability to think critically and to apply our technical skill into a new environment.

When Elliott Fisher from Dartmouth first coined the phrase “Accountable Care Organizations”, he had looked at the organizations that were producing the best quality at the lowest cost and saw that they were creating opportunities for physicians to work together in teams with others, managing the care of the patient across all settings of care, and bearing the responsibility or accountability for both quality and the finances of their patients’ care. That was just technical change for me. That part made sense. Doing this for Medicare Fee-for-Service or PPO patients was another story and something very new. Accountability for patients’ outcomes and expenses without the ability to manage referrals made no sense. That would be impossible, I thought. Then Elliot added a phrase that resonated with me as a challenge to our ability to satisfy patients. He said, “The best fence is a green pasture!”

Elliot’s statement eased the burden of adaptive change. It made sense. The first goal of the enterprise, the ACO, or Big Med should be to provide such complete and accessible care that there would be no desire to leave it. The work is still hard but the path to success is clear. The path is an old familiar path of a guild-like practice. Dr. Spinelli knew that path. As he said to me, “Put the patient first. Solve the patient’s problems and your business problems will improve.”

Most Massachusetts physicians will practice in a Big Med environment in the near future. The era of the solo practice and even the era of small group practice is rapidly disappearing. Ahead is a continuing struggle against the total cost of care with most of us employed and independent only at a personal level of professional attitude. Some of us will work somewhere in the network of a large tertiary system that is connected to communities through the hospitals it controls and their affiliated practices. Some of us will work in an investor backed system of care that owns community hospitals and affiliated practices and seeks to keep care very local and engineered for efficiency. Others of us will work in groups like Atrius Health, led by physicians. We can all come together in our connection to the Medical Society. The society is an effective advocate for patients and physicians. With one voice we can advocate together for our patients and our communities. Our enterprises, no matter how large, do all that they do with acts of care that are connected to us. We control the future. We as physicians can assume a mantle of professional leadership for adaptive change and put the interest of patients first. I do not think we have ever faced a greater problem with more potential impact on our patients or on our economy than the threat we now face. Our new tools have not yet produced the results we need to enable a return to having the right amount of time with our patients and the time to do the critical thinking that we enjoy, yet that is undoubtedly the only way to simultaneously improve quality, reduce cost and improve population health. And we must achieve these results by changing the way that we utilize our physicians since we cannot just throw more resources at this problem. When we solve this problem, we will have truly transformed the delivery of care from a guild to an enterprise that feels like the best of the guild but that handle the complexity of our current environment.

Atrius Health has not yet solved the problem of improving the experience of practice in the Big Med or ACO environment although we continue to work towards that goal. We must keep trying if we hope to ever create the environment of care that patients want where we do the job they want and stay with us because we provide what they value and not just because they have a low cost contract for healthcare that forces them to stay “in network”. As I travel around the country visiting other practices and discussing the issues that face us all with other physician leaders, I see reason to be hopeful but I do not see a definitive solution. I miss the guild-like qualities of practice that we enjoyed in the past and I hope that eventually we will find a way to bring them into our busy world of Big Med. If we do not do this, we can succumb to the misery and disillusionment while we face individual battles with adaptive change. I have confidence that we will choose our patients and the needs of our community over our own and find a way to solve this problem. History suggests that solving problems for our patients is what physicians always do. I believe that we are committed to a better future and will discern how to make it real.

http://www.massmed.org/Oration2012Presentation/#.Vj95q66rSYU