I spent most of Monday watching the impeachment hearings on CNN. Monday was a very dreary day. The sun did not shine through the rain, and the gloom of the day was enhanced by what I heard on television. The high point of the day, its only saving grace, was the fact that NPR broadcasted the hearings which enable me to don my rain gear and continue to listen to the hearings as I took a good walk. It was easier to tolerate the venomous exchanges that went back and forth across the political divide while I was walking than it was for me to sit in my comfortable chair in front of a cheery fire while I listen to presentations.

I should add that I was surprised and pleased by the testimony of Daniel Goldman, the counsel to the Democratic members of the House Intelligence committee. It was his job to present the findings of the Democratic majority of the House Intelligence Committee. He was unflappable and it was interesting to hear his measured responses to all questions that came his way. He was significantly challenged by Representative Doug Collins, the ranking member, and by Representative Jim Jordan of Ohio who is a member of both the Judiciary Committee and the Intelligence Committee. Mr. Goldman never raised his voice and his responses were informative and reasonable. I appreciated the fact that he was able to use his background as a federal prosecutor to explain a lot of confusing legal terms and practical concepts in response to soft ball questions that were tossed his way by Democratic committee members.

The Republican’s lawyer, Steve Castor, is an experienced attorney who has been counsel to Republican members of congressional committees since 2005. His presentation focused on failures of process, and I was surprised at times to find that his point of view and answers often made some sense to me and introduced a plausible “otherside” to many of the certainties presented by Goldman. His focus was not on what had happened, but on the process and the fact that what the president did was arguably within the prerogatives of his office. Prior to the televised Intelligence Committee hearings almost a month ago NPR did a brief overview of both Goldman and Castor.

My intent in presenting Goldman and Castor and discussing the impeachment hearings is not to argue for impeachment or to try to convince you of anything other than to reiterate the reality that we live in an unusual time and that we are struggling to find a way forward despite a political divide that has never been deeper or broader than it is now since the Civil War. I would like to slide from the impeachment hearings to the divides that exist in considering the future direction of the reform of healthcare.

Before, moving to healthcare let me mention once again the unique organization, Better Angels. On their website you can read:

If feelings about our political adversaries can be represented on a spectrum, our objective is to move Americans from Hatred to Respect & Appreciation.

Our approach is guided by the Better Angels Pledge:

- As individuals, we try to understand the other side’s point of view, even if we don’t agree with it.

- In our communities, we engage those we disagree with, looking for common ground and ways to work together.

- In politics, we support principles that bring us together rather than divide us.

The Better Angels are not to be confused with the Better Angels Society which is also a positive organization supported by Ken Burns and other filmmakers. Their objective is to use film to help educate us through our divisions:

The Better Angels Society is a non-profit organization dedicated to educating Americans about their history through documentary film. Our goal is to educate, engage and provoke thoughtful discussion among people of every political persuasion and ideology.

Better Angels doesn’t make films but they do try to improve communications by fostering respect between “red” and “blue” positions. Their publications give a voice to both sides and they schedule events that are “debates” across the divide. I was very impressed by the latest Better Angels newsletter which I received this weekend. I read down a few lines and discovered that it was authored by Luke Nathan Phillips, the “Red” Co-Chair of the Washington D.C. Better Angels Alliance. My first reaction was to hit “delete.” My reflex was, “What do I want to hear from him?” I must admit that it is difficult for me to listen to people whom I expect will upset me with their “distorted” viewpoint. It has been incredibly difficult for me to listen to the comments and questions of Republican House members on the Intelligence and Judiciary Committee. I never listen to Fox News. Why would I want to read what Mr Phillips has to say?

I did catch myself. I reminded myself that I had joined Better Angels in an attempt to be a small part of the solution. I guess it was my Gandhi moment. As Gandhi is reported by some to have “preached,” I reminded myself that the right path was to: “Be the change you want to see in the world!”

If that was my objective I needed to read Mr. Phillips’ thoughts. It was a good essay. A few paragraphs down he wrote:

The air’s filled with the metaphorical winds of change…Impeachment proceedings against our Republican president are underway; the odyssey of the Democratic presidential primary pervades the nightly news; our nation approaches, eleven short months from now, its 59th presidential election under the U.S. Constitution, its 59th opportunity for the citizens of the United States to peaceably decide the administration of their government. It seems that every election, people talk about how unprecedented our times are; this election certainly feels no less unprecedented, and threatens to be perhaps more divisive than many have been in recent memory…

…If you’ll permit me, I’d like to mull a bit over what, exactly, Better Angels is. We are obviously not a political party, nor a voter-registration group, nor merely a civil-discourse organization, nor an advocacy group. Some of us describe ourselves to skeptical onlookers as ‘the nation’s largest fully-bipartisan, grassroots-based, volunteer-led civic organization committed to the work of depolarization across the political divide.’ That’s accurate, but unwieldy. I can think of three other kinds of organizations and movements, with roots deep in American history, that we resemble in our work; thinking of ourselves as modern versions of these movements might clarify, to some degree, what the fundamental nature of Better Angels is.

I will turn his thoughts about the three types of groups into bullet points:

- The first is the local citizens’ council, composed of like-minded citizens organizing together to promote a culture of camaraderie, understanding, and when necessary, civic action. These haven’t always been expressly political- think of the Kiwanis, the Lions, the Rotary Clubs. But organizations like these- from New England’s long town-council tradition, to farmers’ agricultural clubs on the Great Plains in the 1800s, to neighborhood council movements in modern metropoles in the 21st Century- have always formed a backdrop of community-building necessary for political and social action outside the polarized currents of state and national politics.

- The second is the patriotic organization promoting loyalty and service to the American nation. These have taken many forms- veterans’ organizations like the Grand Army of the Republic and the American Legion, civic charities tasked with educating American children, recent immigrants, and others in the nature and practice of American government and citizenship, and emergency volunteer corps dedicated to helping American society through traumatic wartime experiences, like the Red Cross …

- The third is the social movement promoting moral progress and reforms, and then reconciliatory consensus, on key, divisive issues. Most famous of these was the Civil Rights Movement…The Suffragette movement for women’s right to vote, components of the organized labor movement in the early 20th Century, and various movements for the rights of Native Americans, Latino-Americans, Asian-Americans, and LGBT Americans also followed this model. They expanded the civic circle to more Americans than ever, while keeping the circle together.

His conclusion about what Better Angels could be in our times was surprising to me because I totally agreed with his vision which was amazing to me given the fact that he is self labeled as “red” and I call myself “blue.”

I bring this backdrop up to help position Better Angels’s work in the context of American history. Like the citizen’s councils, we try to bring people together at the local level to help them better practice the arts of citizenship. Like the patriotic organizations, our work is informed by a profound love of country, and an exhortation to serve it. Like the reformist social movements, we are animated by a moral vision of unity and fraternity for all Americans.

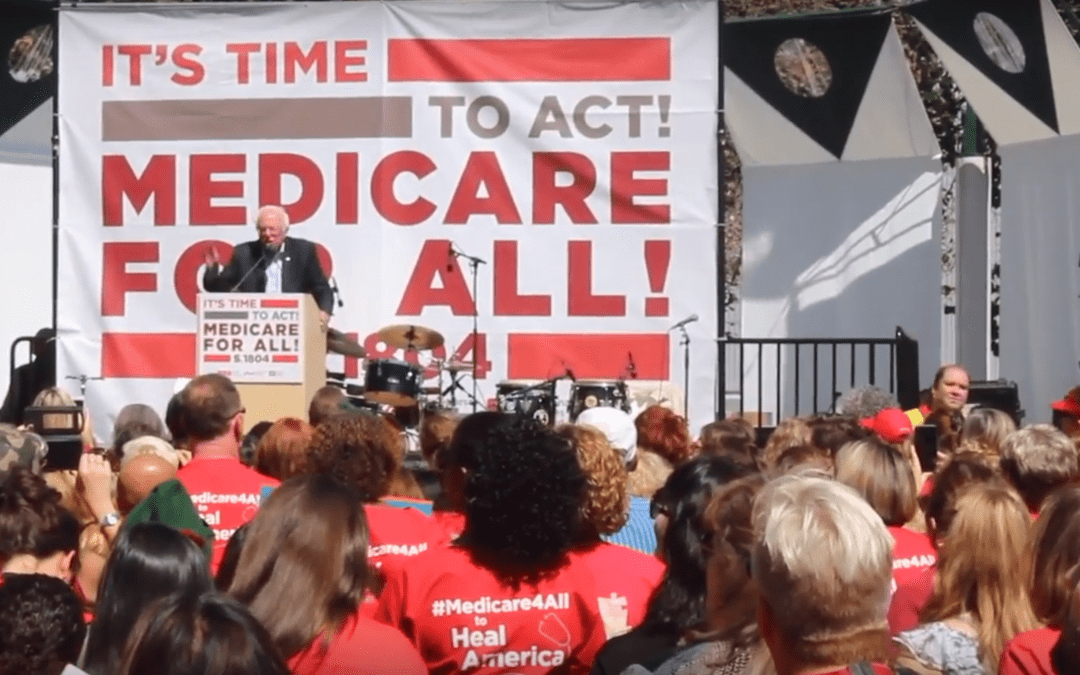

As I was watching the hearings Monday, I kept trying to remind myself that there were “good people” on both sides and that I needed to hear out Congressman Jordan and Ranking Member Collins, whom I was surprised to learn, when I visited his congressional website, is an ordained Southern Baptist MInister and was pastoring a church before he got into politics. Collins’ religious orientation is interesting to me because Harry Truman, Jimmy Carter, Al Gore, and Bill Clinton all were/are Southern Baptists, and I am certain that they would see this moment in history differently than he does. It is an example that labels don’t always reveal the truth about a person’s point of view. As I was watching, I also began to think about the divisions over the future of healthcare that exist within the Democratic Party that will, I assume, be a matter of great discussion and division at the Democratic Debate that will be coming to us on December 19 from Los Angeles. I am sure that there will be at least some debate and also some hard feelings in the fray about the merits of Medicare for all versus the prudence of something less that maintains “choice” and doesn’t destroy the insurance industry or precipitate the loss of over a million jobs in insurance and healthcare finance.

I hope to be able to continue to present both sides of the discussion over the next few months. In time the Democrats will settle on a candidate and that candidate will probably determine the “healthcare plank” of the Democratic Party for the 2020 election. The debate will not end there. There will be more ideas exchanged during election, and then after the election, the debate will continue in Congress. It is my hope, but perhaps I am unrealistic, that somewhere along the way the conversation will move toward common concerns and shared interests.

To get to a shared interest we must hear all the arguments even though listening with respect may be difficult, especially if we are convinced that our ideas are the best ones. Last week I read a provocative column in the opinion pages of the New York Times. It deserves thought and just in case you missed it, I want to bring it to your attention. It may be a surprise to my readers who are in healthcare that many of the readers of these notes are not in healthcare. This article written by Farhad Manjoo makes many arguments that can be understood without the necessity of having an MD, RN, or MPH degree. Perhaps the title is too provocative:

The first two paragraphs set a tone that drips with irony.

Won’t you spare a thought for America’s medical debt collectors? And while you’re at it, will you say a prayer for the nation’s health care billing managers? Let’s also consider the kindly, economically productive citizens in swing states whose job it is to jail pregnant women and the parents of cancer patients for failing to pay their radiology bills. Put yourself in the entrepreneurial shoes of the friendly hospital administrator who has found a lucrative new revenue stream: filing thousands of lawsuits to garnish sick people’s wages.

And who can forget the lawyers? And the lobbyists! Oh, aren’t they all having a ball in America’s health care thunderdome. Like the two lobbyists who were just caught drafting newspaper editorials for state representatives in Montana and Ohio, decrying their party’s push toward a “government-controlled” health care industry. It’s clear why these lobbyists might prefer the converse status quo: a government controlled by the health care industry. If we moved to a single-payer system, how would lobbyists put food on the table, and who would write lawmakers’ op-ed essays?

Manjoo’s point is not that hard to get. When we set our priorities do we protect jobs, companies, and corporate profits as higher priorities than the health of people? He continues by bringing in the disturbing information that our mortality data shows a shortened life expectancy across all groups.

The argument is specious and morally suspect. Last week, health researchers reported that American life expectancy is declining for the first time in half a century, and some of the leading causes have to do with the ruinous health care system. Even if it is the case that reforming American health care might eliminate some jobs, it would seem to be a good trade for the likely benefit: More people might gain access to affordable health care and get to keep living.

He then makes a very uncomfortable point:

But I worry that the jobs argument might sway moderate politicians, centrist pundits and much of the establishment, because it plays on one of the major fault lines of health reform: that in fixing the system so that more people benefit, those who now enjoy a privileged slice of American health care might end up worse off than they are today…in America, “I’ve got mine and I don’t want to lose it” is always pretty good politics.

He is not all irony. He has done some research.

The jobs argument goes like this: There’s a lot of fat in the American health care industry, and any effort to transform it into a simpler system in which everyone is covered would necessarily eliminate layers of bureaucracy and likely reduce overhead costs. Every year Americans collectively pay about $500 billion in administrative costs for health care — that is, for things like billing and insurance overhead, not for actual medical care.

These costs are significantly higher than in most other wealthy countries. One study on health care data from 1999 showed that each American paid about $1,059 per year just in overhead costs for health care; in Canada, the per capita cost was $307. Those figures are likely much higher today.

Wouldn’t lowering overhead costs be an obviously positive outcome?

Ah, but there’s the rub: All this overspending creates a lot of employment — and moving toward a more efficient and equitable health care system will inevitably mean getting rid of many administrative jobs. One study suggests that about 1.8 million jobs would be rendered unnecessary if America adopted a public health care financing system.

He again makes us uncomfortable by forcing us to think about the motivation for our position if we oppose Medicare for all.

Indeed, that’s exactly what Biden’s presidential campaign is saying about the Medicare for all plans that Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders are proposing: They “will not only cost 160 million Americans their private health coverage and force tax increases on the middle class, but it would also kill almost two million jobs,” a Biden campaign official warned recently.

The next paragraph is aggressive:

Note the word “kill” in the statement. That word might better describe not what could happen to jobs under Medicare for all but what the health care industry is doing to many Americans today.

Manjoo goes back to the data about the changes in life expectancy. He sites what we all know about the epidemic of opioid deaths, but he does not stop there.

Opioid addiction isn’t the only factor contributing to rising American mortality rates. The problem is more pervasive, having to do with an overall lack of quality health care. The JAMA report points out that death rates have climbed most for middle-age adults, who — unlike retirees and many children — are not usually covered by government-run health care services and thus have less access to affordable health care.

The researchers write that “countries with higher life expectancy outperform the United States in providing universal access to health care” and in “removing costs as a barrier to care.” In America, by contrast, cost is a key barrier. A study published last year in The American Journal of Medicine found that of the nearly 10 million Americans given diagnoses of cancer between 2000 and 2012, 42 percent were forced to drain all of their assets in order to pay for care.

If he has not angered or offended a majority of Americans at this point he takes one final shot as he finishes.

The politics of Medicare for all are perilous. Understandably so: If you’re one of the millions of Americans who loves your doctor and your insurance company, or who works in the health care field, I can see why you would be fearful of wholesale change.

But it’s wise to remember that it’s not just your own health and happiness that counts. The health care industry is failing much of the country. Many of your fellow citizens are literally dying early because of its failures. “I got mine!” is not a good enough argument to maintain the dismal status quo.

Now I will be ironic. I guess he thinks his column will convince us all to put the health of the nation and the risk of the 30 million Americans without care, and the 80 million Americans who have care that is inadequate, over our own care, our own taxes, and our own fears about our jobs. He does not mention that theoretically it would be easy to move the skilled workers in insurance companies and health systems billing operations into other industries. We have huge workforce shortages in other industries that would love a larger labor pool. I hope his column generates some thoughtful responses. I would love to hear an equally articulate response from someone who can show us how we can achieve the Triple Aim within the confines of the status quo, or by just adding a public option while preserving commercial insurance. Whether the subject is impeachment or the struggle for the Triple Aim, most subjects that are laden with emotion have complexity that deserves discussion and a search for common ground. The greatest impediment to progress in our desire to overcome all of our divisions is our inability to overcome our anger and and our antipathy for those who hold a different view long enough to listen to each other with the hope of finding some common ground upon which we might build a lasting solution to a complex, emotion laden problem.