It has been another bizarre week. During times like this in the past, for example during the “dot com” bust of 2000, I might have just shrugged my shoulders and uttered a small prayer asking for personal protection before returning to more important responsibilities. That market threat seemed small to my world compared the 1999 financial collapse of Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare. In 2000, I was still totally consumed by the attempts of our practice to adjust to the sudden loss of over one hundred thousand patients who switch from the sinking ship of Harvard Pilgrim to other insurers with which we had no contracts. As chairman of the board, I felt a high level of responsibility to the resolution of huge problems that few people could see coming. I had been asked to leave the finance committee of Harvard Pilgrim when I pointed out that we were walking on thin ice when we offered services with a medical loss ration greater than 1.0. I felt that selling a dollar’s worth of healthcare for 90 cents to gain market share was not a sustainable strategy. Others on the Harvard Pilgrim finance committee disagreed and invited me to join another committee. I had been concerned about decisions that seemed too business oriented, and had fought for the opportunity to bring an unwanted doctor’s perspective to the finance committee. There was no solace in saying, “I told you so!” as our corporate ship was sinking.

The experience taught me the importance of leadership that tried to “look over the horizon.” By this time in my medical practice I had learned that I had a greater responsibility to my patient than to just focus on today’s problem. In a long term trusting relationship I owed my patient the attention to consider the question of what might be the future threats to this person. Having asked that question, I had a professional responsibility to construct, or at least consider, plausible strategies that might mitigate or ameliorate what I realized might be a threat. I don’t like poorly considered “optimism.” I have always believed that “hope needs a plan” and that those who chose to lead have a sacred obligation to be concerned about how to avoid, or at least manage, the uncertainties of the future. Leaders must do the inconvenient work of considering threatening possibilities that might become the reality rather than the successes they tell everyone to expect. Contingency planning, or taking the “long view,” is hard work and never fun, but it is essential to responsible professional behavior. Along the way, I came to appreciate the importance of considering “material risk.” I came to define the term for myself as something that probably won’t happen, but if it does it will be a disaster. A leader has a moral responsibility to consider the whole range of possibilities that the future might present, and have a pre considered strategy for each possibility. This week is an example of the jeopardies we are exposed to when our leaders are so consumed with getting rich or getting great that it becomes impossible for them to apply adequate attention to alternative outcomes of “what might be.”

Between 1999 and 2005 there were tough days for me as chairman of our board that made me oblivious to what was going on in the larger world. In a little less than two years after our “launch” or spin off from Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare on January 1, 1998 as an independent 501c3 non profit multi specialty medical practice, we had lost both our CEO and CMO, and the source of 98% of our business was in receivership. My attention then was consumed by trying to work with others on the board of Harvard Vanguard from being sucked into financial oblivion by the failure of Harvard Pilgrim Healthcare. Saying, “I told you so!” provided no relief to the realities we faced. Eventually what saved us was the ability of a creative new CEO that we hired to show the value we offered in our our connectedness to other organizations, employers, hospitals and insurers, that considered us to be a damaged but valuable member of the community that they wanted to continue, even though at some level we were their competitors or had conflicting interests. During that time I learned to appreciate the counter intuitive concept of “coopetition” that I still believe will be essential to the future of healthcare and our ability to approach the objectives of the Triple Aim.

With the help of others in the form of grants, favorable contracts, and an internal restructuring of our assets, we were doing well by 2008 as the markets went into a freefall after the failures of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. By 2008, I was also approaching retirement, and was paying a little more attention to my personal finances, but was not well informed about how I should react. As the Dow went below 10,000, on its way toward the low of 6,469.95 that it hit on March 6, 2009, my wife and I decided to sell a substantial amount of what was in our 401k. By the time it hit bottom, the market had lost 54% of its value from its previous high of 14,164.53 on October 11, 2007 and we had lost more money than I would like to admit. We were not alone in our error. What we learned was that it is hard to be objective under stress, and that we needed to find someone whom we trusted as a guide and advisor, or I would be working forever.

Yesterday was the worst day for the market since the selloffs of 2008-9. When bad days happen we are given a gift that we can accept or reject. There is nothing like loss to focus your perspective and reorient you to fundamental principles. Bad times reveal a lot to those who are willing to peer into the abyss.

When I ask myself what I have learned over the last six weeks I come up with a few observations that I feel a need to share. There are many ways to say the principle that stands out for me, but to demonstrate a distant knowledge of English literature, let me remind you of John Donne, a remarkable man who graduated from bad behavior to great judgement, talent and responsibility. For the last ten years of his life, from 1621 until he died in 1631 at the age of 59, he was the Dean of Saint Paul’s Cathedral in London.

‘No Man is an Island’

No man is an island entire of itself; every man

is a piece of the continent, a part of the main;

if a clod be washed away by the sea, Europe

is the less, as well as if a promontory were, as

well as any manner of thy friends or of thine

own were; any man’s death diminishes me,

because I am involved in mankind.

And therefore never send to know for whom

the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.

MEDITATION XVII

Devotions upon Emergent Occasions

John Donne

Donne was a womanizer who squandered his inherited fortune. He was a romantic whose marriage broke rules that landed him, the priest who performed the marriage, and the witness to the secret marriage in jail. Along the way in life he became a man of letters, a politician, and finally a priest while fathering twelve children. I think it is possible to imagine that as he grew in wisdom and experience he progressed from thinking principly about himself to realizing his connectedness to everyone else.

As a priest, he was aware of the admonition of Christ that is also present in almost all of the world’s great religions, that all of us, with no exceptions, are worthy of honor and attention, especially when we are in need, because of our common humanity and the image within us of our creator. One need not be religious to accept that our moral responsibilities extend past self and family to our neighbors, and beyond neighbors to strangers. As our planet gets smaller and our interdependencies become both the origin of our accomplishments and the great risk for our collective failure, Donne’s wisdom is worth reviewing.

When I first read Donne’s poem over fifty years ago, I had the feeling that it was advice for others at another time. During the last fifty years there have been many reminders in my own life that what I do does impact others, and what others do impacts me. The “golden rule” of do unto others as you would have them do unto you is an admonition upon which all civil society is built. An improved version of that truth is “Do unto others as they would have you do unto them.” Unfortunately, one of the most remarkable qualities of human beings is that we frequently forget some of our most critical operating principles. Sometimes we don’t forget operating principles or “rules,” but we ignore them for “expediency” or worse yet try to “game” the principles for personal or national advantage. Like the story of the fall of Adam and Eve in the garden, we are also gullible to others convincing us that the “smart ones” can ignore the rules. We are always fools when we accept their advice to put what is best for us, or a subset of us, at the top of our objectives, and be winners. We are lying to ourselves when we justify our greed by saying that in time what is good for us will trickle down to the less fortunate among us.

How many times have you heard that the most important job of the president is to protect every American? That is actually a debatable opinion although Bush II, Obama, and Trump have all made the statement as a justification for their actions. In the article connected to the link, Daniel Bush and Travis Daub write:

“The first and most important priority of the president of the United States is to protect the safety and security of Americans,”

That’s a line that will likely be repeated often between now and January 20, 2017, when President Barack Obama’s successor is sworn into office. But on that day, the next president-elect will stand before the American people and say something categorically different about the new job:

“I do solemnly swear that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.”

Despite the oath and its focus on the constitution, presidents — and presidential candidates — often redefine the job description to suit their own interests.

Our current president is not a man of letters or a student of history, nor is he conversant in philosophy or science, but has declared himself to be “a very stable genius.” He does have an unusual form of genius as was documented in the book by Philip Rucker and Carol Leonning the Washington Post reporters who recently published A Very Stable Genius: Donald J. Trump’s Testing of America. Dwight Garner notes in his New York Times review of the book written this January that it reveals what should have been obvious to all of us all along.

It reads like a horror story, an almost comic immorality tale. It’s as if the president, as patient zero, had bitten an aide and slowly, bite by bite, an entire nation had lost its wits and its compass.

Garner is prophetic. He is describing the president’s self centeredness and oblivion to the needs of others, and his disregard for truth as a potential pandemic. As I pondered these ideas and the crescendo of events during this last week, I decided to go back and review the president’s State of the Union address, delivered just a few weeks ago on February 4, 2020, shortly after he had been “exonerated” by Republican senators from the charges that resulted in his impeachment. I thought that I would let his own words demonstrate just how unaware he was of how he was of the reality that he was neither defending the Constitution or protecting the American people as bragged about how great he is and how much he has accomplished. As he was laying out his “accomplishments” as the foundation for his reelection, he was totally unaware of the fact that even as he spoke, the floor of our national stability was melting under his feet, and a time bomb was ticking in his most favorite temple of his “greatness and genius,” the stock market. He begins:

Three years ago, we launched the great American comeback. Tonight, I stand before you to share the incredible results. Jobs are booming, incomes are soaring, poverty is plummeting, crime is falling, confidence is surging, and our country is thriving and highly respected again. (Applause.) America’s enemies are on the run, America’s fortunes are on the rise, and America’s future is blazing bright.

The years of economic decay are over. (Applause.) The days of our country being used, taken advantage of, and even scorned by other nations are long behind us. (Applause.) Gone too are the broken promises, jobless recoveries, tired platitudes, and constant excuses for the depletion of American wealth, power, and prestige.

Our recent experience reveals that the complexity and chaos scientist, Edward Lorenz, who noted that the world is so interconnected that when a butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil we could have a tornado in Texas, may have been exaggerating, but his concepts of how a complex world really works in surprising ways is closer to the truth than the assertions of this man who demands constant adulation of his genius. Now in a state of national concern, as Italy is closed for business, as Harvard tells its students not to return from spring break, as people are trying to work from home, we have learned that this genius not only did not have a plan, he did not see a need for a “pandemic team” in the White House. Even after past concerns about ebola, MERS, and SARs, the infrastructure of our ability to respond to new threats has been dismantled as the CDC has been the victim of budget cuts and administrative neglect.

The collective mismanagement of the Trump administration’s handling of the crisis since scientists noted “something unusual” in China several months ago will be an ongoing revelation, but we know enough to make us cringe in fear as documented in an article entitled “The unique incompetence of Donald Trump in a crisis: When bureaucratic mistakes are compounded by political incompetence.” The article appeared yesterday in the Washington Post and was written by Professor Daniel Drezner of the Fletcher School at Tufts. I think much more will come out later as epidemiologists and other scientists join policy experts in reviewing the errors in the management of the Covid-19 experience for the benefit of future generations. Professor Drezner writes:

The bureaucracy — composed of the experts dedicated to solving the problem — royally screwed up its initial handling of the crisis. The Department of Health and Human Services overruled the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in how infected Americans trapped in Japan were brought back to this country. According to a department whistleblower, HHS also appears to have bollixed its handling of Americans returning from Wuhan, China, leading to community spread of the virus in California.

The CDC is hardly blameless. Its initial test for the coronavirus was faulty. Furthermore, long-standing bureaucratic rivalries led to absurd moments like an FDA official getting locked out of the CDC’s Atlanta headquarters.

So let’s be clear, the experts were far from perfect in handling the initial stages of this crisis. And the politicians, as with the Ebola outbreak, also radiated a false sense of calm. In January and February, the Trump White House kept insisting all was well, even though it very clearly was not.

The result has been a passel of stories in the past 72 hours that all arrive at the same conclusion: The United States blew its window of opportunity to prepare for the pandemic that is now about to happen.

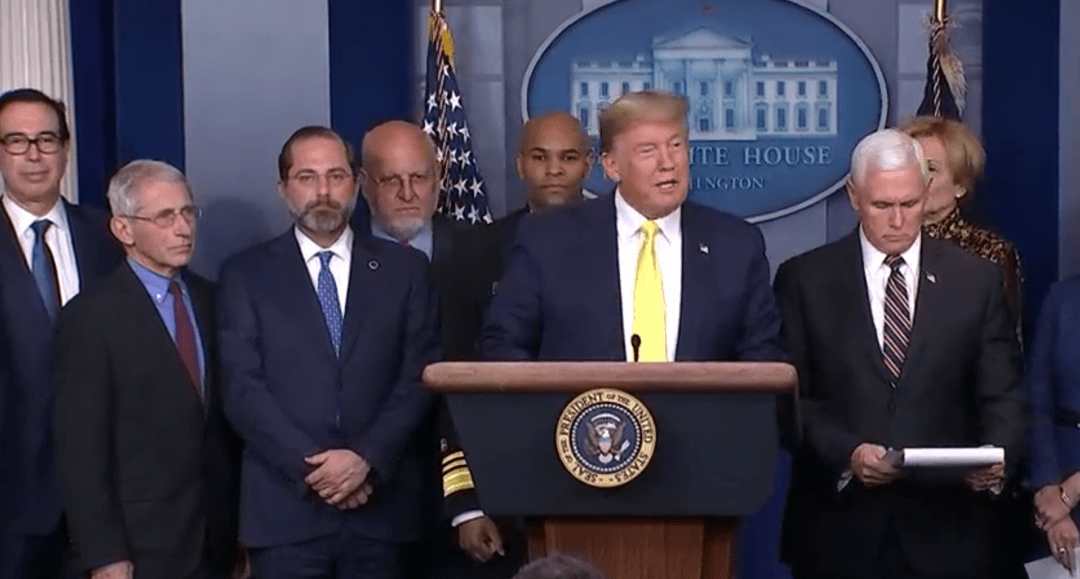

The article documents many of the failures that have already occurred, and I am sure that others will be documented as time goes on, but perhaps the one reality that this president is directly responsible for is the environment of fear that exists with in his administration. We are told that all conversations with him must avoid facts that will upset him. Any exchange with him begins after an exclamation proclaiming his greatness. An environment of fear that precludes the transfer of important, but uncomfortable information, is an environment that fosters disaster. I must say it again, fundamental to the totality of this administration’s failures is the fear of the president’s rath that the leaders of our agencies have of offering an opinion that will displease the president. Late yesterday afternoon there was an impromptu press conference that I assume was designed to falsely assure the public that everything was under control. As I was listening to the Vice President’s “report” which was most remarkable for his fawning praise of the president’s genius, I realized that what I was watching was proof of Professor Drezner’s observations and evidence that we have now advanced to the place where the most appropriate response the mess we face is “heaven help us.”

As I reviewed the entirety of the official transcript of the State of the Union Address, I found evidence of the false reassurance that Professor Drezner identifies. After going on for over an hour documenting his accomplishments that are derivative of his genius, he diminishes the threat that may turn his presidency into a Hoover like disaster for all of us. It sounds good, but time has shown his words are usually lies. He wears a thin mask behind which there is the very dangerous lack of knowing when he is on the brink of disaster. Does he even know that he is lying when he tells you what he wants you to believe is true? Surely there must be some aides around him who know that what he is saying is mostly bogus.

Protecting Americans’ health also means fighting infectious diseases. We are coordinating with the Chinese government and working closely together on the coronavirus outbreak in China. My administration will take all necessary steps to safeguard our citizens from this threat.

Really? That is hard to believe, since it follows a very misleading description of all the good things that he has done for healthcare. In retrospect, we can clearly see that the centerpiece of his accomplishments, the stock market, is now vulnerable, as is the transient wealth his genius has created by abusing the underserved among us and forcing all of our allies to “pay up.”

Since my election, U.S. stock markets have soared 70 percent, adding more than $12 trillion to our nation’s wealth, transcending anything anyone believed was possible. This is a record. It is something that every country in the world is looking up to. They admire. (Applause.) Consumer confidence has just reached amazing new highs.

All of those millions of people with 401(k)s and pensions are doing far better than they have ever done before with increases of 60, 70, 80, 90, and 100 percent, and even more.

We were all doing better on February 4 than we are now on March 10. Where is Frank Sinatra to sing “That’s Life!”? We can change the words and sing “riding high in February , shot down in March” It’s easy come, easy go. My consumer confidence in the incompetence of this president to manage the moment he doesn’t understand or admit is so high that my wife and I, along with two other couples, just cancelled a June cruise on the Danube between Budapest and Prague. South by Southwest, a 350 million dollar annual benefit to Austin, Texas was just cancelled. It’s hard to keep up with what is cancelled. It is true that no man is an island and that we are all connected which brings me to the issue of healthcare policy.

On many occasions I have tried to make the point of our healthcare connectedness in these notes. Ultimately none of us can rest assured in our own health if our neighbor’s health is not also assured. Will we offer the “illegal aliens” in our country testing and support if they have symptoms of Covid-19 infection? Do we want to know if they are a part of a chain of contact? Viruses are not excluded by border fences. Do we allow those who live from paycheck to paycheck, the working poor, to be quarantined and kept from their workplace for fear that they may have had contact with someone who could be a carrier? Do you think that everyone who is vulnerable to eviction if they can’t come up with next month’s rent is going to cheerfully stay home from work? The shutdown of the government in the recent past showed us just how vulnerable “middle class” workers are to the loss of one paycheck. They had good benefits and a steady paycheck. We know that forty percent of Americans are vulnerable to an unexpected bill of $400. That certainly must mean that at least 40% of us are vulnerable to a loss of $400 dollars of income.

If you have excellent “coverage” you should be terrified that there are millions who don’t and may think more of their own economic vulnerability than your health since we have given them no reason to believe over the last three years that we care much about them. In many ways this president acts as if they and their families, along with the environment we share, are disposable.

Italy is worthy of our attention. Every hospital is stressed. 9000 people are sick, and over 600 have died. The hospitals where I live, and the emergency response services where I live, are trying to prepare for what might happen. Today’s headline in the Valley News is “Planning For An Outbreak.” We are preparing for the possibility that in a few weeks we might have the same experience that has closed Italy. Atul Gawande has warned us that in healthcare incompetence is as dangerous as ignorance. One would hope that as a nation someday we will care enough about one another to develop the competence to anticipate and manage the new threats about which we have no prior experience until we develop the knowledge to defeat them. That skill requires a different kind of genius than this president possesses.

Perhaps as a positive derivative of this scary and disappointing moment we will move toward a greater understanding of our connectedness and shared vulnerabilities even if that understanding is wrapped in very inhuman descriptions of our individual roles. In a Trumpian world my greatest value to the collective good these days is as a “consumer.” People in other countries are valued as parts of a “supply chain.” Have we all become commodities or objects of greater or lesser value to the perpetuation of a narcissistic worldview that can not integrate into its voracious appetite for self indulgence the principles that it never understood that fuel the engine that produced all the things which it claims as the products of its genius?

Professor Denzer hits the nail on the head when he describes the origin of the problem, and how it varies in outcome from the ebola scare of a few years ago when Barack Obama was president. He says there are three essential differences. I will note his description of the first difference:

First, Trump’s toddler traits have exacerbated the mismanagement of the situation. The president’s short attention span and quick temper compromised his administration’s ability to handle the crucial weeks when containment was still possible.

The great Will Rogers was famous for his humorous descriptions that exposed the truth. You may remember his assertion that he was not a member of an organized political party. After a short pause he continued by saying, “I am a Democrat.” One of my favorite Will Rogers witticisms is his description of how Congress worked in his era. He said:

This country has come to feel the same when Congress is in session as when the baby gets hold of a hammer.

That quote popped into my head when I read Professor Denzer’s description of the President’s failures in the context of “Trump’s toddler traits.” I guess that since our Congress has become irrelevant and ineffective as the result of the ineptitude of some critical number of its members, the hammer has been taken up by the toddler in the White House. I once wondered if we could survive four years of his narcissism. Now I wonder if we can make it to the election.

As I write these complaints and concerns, I have three prayers. The first is that this storm passes, and passes quickly. I think it is possible that the virus will run its course, or that some combination of the actions being taken after great delay will make a difference, and the medical consequences for us will be mitigated. I hope it is not too late to prevent the loss of tens of thousands of lives. I hope that the damage done to the world’s economic relationships will heal quickly, but that may not be as likely as the quick reduction of the viral threat given the compounding factor of the price war over oil between Russia and Saudi Arabia, and the downstream effect of the losses of production and consumption that have already been initiated. There will be inevitable further economic damage before the storm passes.

My second prayer is for those of you who must provide for the mental, emotional, and physical health of a nation and a world that is so stressed and worried. Those attempts at positivity lead me to express one other hope projected into the future that might make this a positive experience. We have a collective capacity to learn. I pray that we might learn that we should collectively avoid following any wannabe leader who has a worldview that would divide us form one another, and who does not understand the interdependencies that are the origin of both our achievements and our failures.

In his book The Narcissist Next Door: Understanding the Monster in Your Family, in Your Office, in Your Bed-in Your World, Jeffrey Kluger reminds us that no matter how exciting the initial encounter is with a narcissist, things always end badly. His advice is to recognize the problem and move on from the relationship while you can. I would add that as we move on, we should collectively ask ourselves, “What part of the problem were we? What about us made this disaster of collective relationships possible? There may be worse things that we can avoid in the future, if we can learn something in this moment. We can be sure that there will be other viruses and other unimagined challenges in the future that will threaten our world, and we will continue to be very vulnerable if we deny our connectedness on this small planet.