The “serious” section of Friday’s post was entitled “Preparing For Transformation.” At the end of the post after talking about the transformation that Joe Biden was trying to lead as we emerge from the pandemic I promised that I would be returning to the subject of transformation. I had been describing the personal transformation that pundits like Ezra Klein were recognizing in the president, but I could have been referring to the need for transformation in the country that was the observation and opinion of pundits like David Brooks and E.J. Dionne. There is no question in my mind that “transformation” in our collective thinking, in our politics, in our economy, and in our professional lives should be the driving theme of this year. I finished the piece by writing:

I will leave it to you to put forth your own explanation for the Biden we have at this moment. The more important concerns are what will this Biden be able to accomplish with your help and what is the transformation you need to undergo to join the effort to create the equitable world we want or if that is too far to reach insure that we will not slide back into the world we just threw off with great effort after great losses.

That is the conversation that I want to join, and I hope to explore over the next several weeks. How will we be transformed? How passive or how active will you be and how will we prioritize our objectives? There is a lot to consider.

The link attached to David Brooks’ name above is from a column that he published last Thursday where he argued that “the heart and soul of the Biden project is a ‘daring revival of the American System.’” I love the first two paragraphs which describe his thesis:

What is the quintessential American act? It is the leap of faith. The first European settlers left the comfort of their old countries and migrated to brutal conditions, convinced the future would be better on this continent. Immigrants all crossed oceans or wilderness to someplace they didn’t know, hoping that their children would someday breathe the atmosphere of prosperity and freedom.

Here we are again, one of those moments when we take a leap, a gamble, beckoned by the vision of new possibility. The early days of the Biden administration are nothing if not a daring leap.

Brooks implies that Republicans don’t seem to sense the importance of this moment and the fact that our form of democracy is well on its way to losing its influence on the world to China. The Chinese political machine has been able to deliver progress through the sort of authoritarian approaches that Donald Trump’s actions and words lead one to believe that he and many of his supporters would have liked to import here.

Brooks is a self-described conservative, but I frequently find that his reasoning works just fine in the progressive framework that I imagine that I live within. Deep into the piece he explains what he sees in references to our history.

Some people say this is like the New Deal. I’d say this is an updated, monster-size version of “the American System,” the 19th-century education and infrastructure investments inspired by Alexander Hamilton, championed by Henry Clay and then advanced by the early Republicans, like Abraham Lincoln. That was an unabashedly nationalist project, made by a youthful country, using an energetic government to secure two great goals: economic dynamism and national unity.

At the end of the article, Brooks positions us as being at a crossroads. Biden essentially did the same thing in his speech that introduced his “infrastructure” bill, The American Jobs Act. If you missed my thoughts on the president’s proposal, check out my post from April 2nd. Brooks argues that there is an urgency that requires that we take chances that will result in a change of direction that I would say is the equivalent of a transformation this way:

But we’ve had 20 years of anemic growth and a long period of slow productivity growth. The current trendlines cannot continue. These are necessary and plausible risks to take if America is not to drift gentle into that good night…The Biden plan is what has already worked locally, just on a mammoth scale.

Sometimes you take a risk to shoot forward. The Chinese are convinced they own the future. It’s worth taking this shot to prove them wrong.

For years I enjoyed the Friday afternoon “debates” on NPR between E.J. Dionne and David Brooks. I always thought that their conversations were a perfect model for a positive bipartisan conversion. If you compare Dionne’s column from March 31 that’s entitled “Opinion: Biden is transforming the nation’s political assumptions” to the Brooks column from last Thursday you can see that once again they have found that they see the moment in much the same way. Dionne is being specific about the Biden transformation when he says:

The president is transforming the nation’s political assumptions by insisting that active government can foster economic growth, spread wealth to those now left out, and underwrite research and investment to produce a cleaner environment and a more competitive tech sector.

Dionne quotes Biden:

“Historically, infrastructure had been a bipartisan undertaking, many times led by Republicans. There’s no reason why it can’t be bipartisan again. The divisions of the moment shouldn’t stop us from doing the right thing for the future.”

He then makes a statement that may be more hope than fact given the reality that so far no Republican has found much to accept in the president’s use of an expanded definition of infrastructure to drive a national transformation. Brooks’ post written a week later was totally aligned with the opinion of Dionne. They both endorse an active government that seeks to lift the underserved and move the nation toward greater equity while improving our stewardship of the environment:

The president is transforming the nation’s political assumptions by insisting that active government can foster economic growth, spread wealth to those now left out, and underwrite research and investment to produce a cleaner environment and a more competitive tech sector.

There will be nothing more important and interesting to follow between now and July than the progress of the American Jobs Act as it is considered and modified in Congress. You can be assured that I will try to keep you up to date on this critical process as the drama unfolds. But my question at the end of the piece last week was not whether Biden’s transformation would result in a bold new law for more jobs, a better environment, and a more secure future for the country as it increased equity and opportunity for many Americans who have been chronically disregarded and disadvantaged. My question was to you and the people with whom you work.

How will we be transformed? How passive or how active will you be and how will we prioritize our objectives? There is a lot to consider.

That is the same question that I asked myself in February of 2008 when I began my tenure as CEO at Atrius Health and Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates. It was the core question that was at the root of all that I wrote in my Friday letters for the next six years as CEO and that has been a major motivator behind most of the posts for the last six years. During the six years that I was CEO, I made dozens of presentations every year within our organization and an almost equal number of speeches and panel discussions outside our group. I considered the transformation of healthcare to be an urgent need even though I knew that both within our group and within the wider community there were many who were just paying lip service to the idea. I discovered that it is human nature to resist change and that there is no better strategy, either conscious or unconscious, to “kill” an idea or a movement than to embrace it and then neglect it. I now consider that to optimally serve its patients and the country healthcare needs to be even more direct and consider the need to be even more urgent now than I did in 2008.

President Biden is modeling what happens when a leader leads transformation. Leading a transformation may be the most difficult test for a leader. Gandhi is reported to have said that we must be the change that we want to see in the world. John Toussaint effectively applied that idea to attempts to transform healthcare in his 2015 book, Management on the Mend: The Healthcare Executive Guide to System Transformation. In the second paragraph of “Chapter 1: Laying the Foundation,” he writes:

The first step in your prework, after all, is recognizing that change is necessary. Step two is admitting that you need to change…Most of us need to change a lot.

If you pride yourself on your ability to make quick decisions and set people straight, your leadership style is going to need an overhaul. If you have decided that you can delegate the work of change to middle management, you need to adjust that, too.

My own belief that we needed to transform all of healthcare beginning with our practice evolved slowly over the late eighties and through the nineties. It is hard for me to know if that slow metamorphosis would have occurred without the influence of Don Berwick and my close proximity to him and respect for his values. I think that my slowly developing awareness was not an atypical path. We often have colleagues who are on the leading edge of evolving thought who understand the need for change before it is obvious to most of us. We often go along with those we respect before we fully understand the subject or the threat. The need for change in healthcare was initially driven by a growing awareness of our deficiencies in quality and safety. I was fortunate to work in an organization where quality and safety concerns were part of the DNA of the organization. Our practice had superior measurements for quality going back to its earliest years, but in a way that was a liability because when we compared ourselves to other medical practices we were satisfied to be better than they were and had no real goal to be better than we were. As the saying goes, “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” Our pride in our superior status left us unable to see our continuing deficits.

Many of us had our eyes opened by the publication of Crossing the Quality Chasm in 2001. We were able to look at its recommendations and then look in the mirror and see where we had substantial work to do. Quality in healthcare was given a very different description than most of us had ever considered. Many of us had operated with a technical concept of quality and did not fully appreciate it as a property of “systems.” It was not like having the gift of perfect pitch or the ability to run a hundred yards in under ten seconds. Quality needed to be engineered into our practices. Attitudes and mechanism of care delivery were foundational to care that met the new definition of quality which was care that was:

- Safe—avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them.

- Effective—providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively).

- Patient-centered—providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.

- Timely—reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care.

- Efficient—avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy.

- Equitable—providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status.

One of the most difficult tasks in the transformation process is to sell the need for change. It is difficult to convince doctors and institutions who believe that they are exemplary that they are on a path that will ultimately create even more problems for the people that they think that they are serving well. If you are satisfied that your care is safe and convinced that you are effective, it is often quite difficult to realize that you do not demonstrate patient-centeredness, waste the time of your patients, and often allow delays in care that compromise outcomes. Even if you accept that you are safe, effective, patient-centered, and provide timely care it is difficult for you to hear that your care is not efficient ( too costly) and that you are part of a system that is not equitable.

Berwick, Nolan, and Whittington took us one step further in 2007-2008 with their statement of the Triple Aim. The Triple Aim represented the practice target for all the transformational efforts that Crossing the Quality Chasm recommended. If you follow the link you realize that the defining paper was published a few months after I assumed my leadership role.

I would like to say that my efforts to lead a transformation of our practice were motivated solely by the Triple Aim and the concepts of quality as described in Crossing The Quality Chasm, but that would not be true. I was driven more by the wisdom of Sister Irene Kraus who put forth the most succinct statement of reality in healthcare which is, “No margin, no mission.” To ground this basic axiom of survival as necessary for the opportunity to improve performance in the domains of quality, it is necessary that every aspect of the enterprise become so efficient that the organization can simultaneously be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, and equitable within the resources that are available, or that its revenue is a reasonable distribution of all of the public’s resources as our government attempts to balance the multiple needs that must be addressed. This reality brings us back to the president’s need to equitably fund his American Jobs Act. .To be explicit, for a long time healthcare has neglected its responsibility to be good stewards of the public’s resources. The cost of care for the efficiency and equity of the results we get is a national disgrace. Joe can’t guarantee quality for every individual, improved health for the nation, and a reduction in healthcare’s share of the nation’s resources. Only you and I can do that. The role of the healthcare establishment over the last hundred years in the efficient and equitable delivery of care is disgraceful. If that makes you upset, I am sorry because there are tons of papers and thousands of terabytes of data to support my statement.

In 2008 it was obvious that the margin of our practice and of most healthcare institutions were maintained simply by asking for more resources each year. That was why the cost of healthcare was approaching 20% of GDP even though there were tens of millions of disadvantaged people who got no care. Intuitively, I reasoned that annual double-digit increases in the cost of American healthcare was unsustainable. This is made particular sense to me since by then we were into the worst of The Great Recession of 2007-2009. I quoted “Stein’s Law,” If something can’t go on forever, it will stop.” Applying that reasoning to our practice, it was clear that we needed to make some changes if we were to hope to simultaneously pursue the six domains of quality and the Triple Aim and not go into bankruptcy. The most obvious solution to the dilemma that faced us was to reduce the huge amount of waste in our practice and in every other practice. We needed a “transformation.”

I will suspend the story here and plan to continue the discussion over the next few posts. Consider this to be the second installment in an ongoing story. There is much more to tell, and I think there are lessons to be learned.

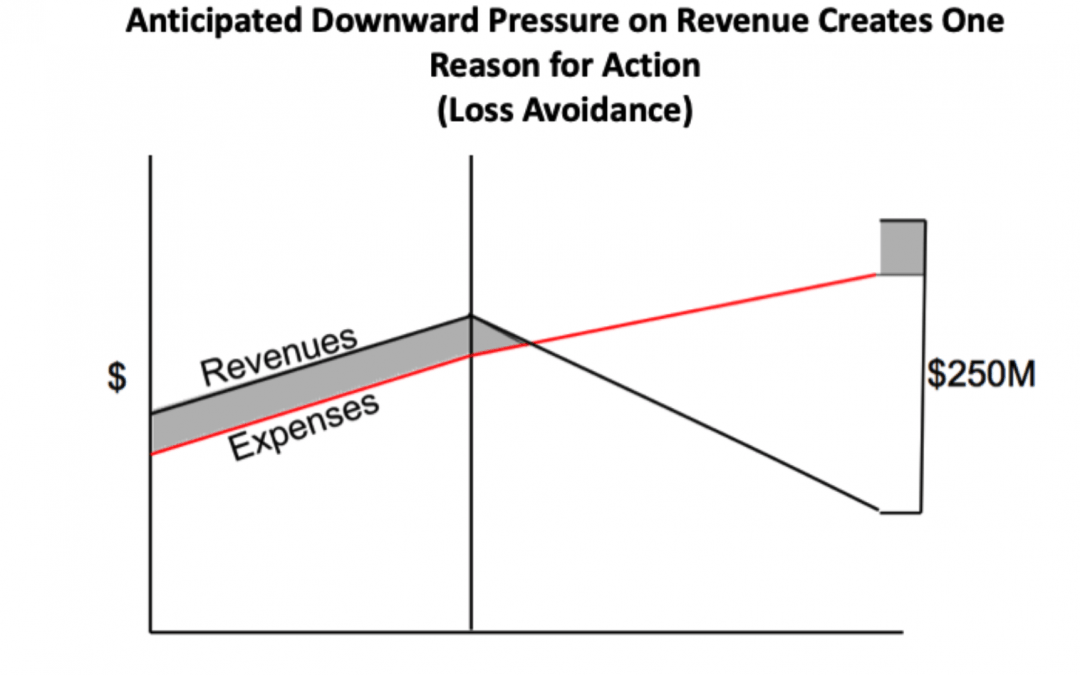

The graphic in today’s header was an attempt created by our CFO, Tom Congoran, to demonstrate in a clear and concise way the consequences of rejecting transformation. The upsloping parallel lines of revenue and expense represented the accepted 8 to 10% year over year inflation of the cost of care. The sharp downward deflection was what would happen if revenue increases were reduced to something more reasonable like the annual growth in GDP which is what happened by law in Massachusetts in 2012. This slide was produced in 2009.

The only way to maintain the quality and safety of the practice when revenues fell would be to prospectively prepare for the reduction in resources that would inevitably occur, which they did. My job as CEO and the job of the board and the leadership team was to anticipate what was coming and work with our managers and clinical leaders to send the need for transformation to every corner of the practice. It takes a few years and great effort against substantial internal resistance to lead such a transformation.

Failure to prepare means that when the change inevitably comes the only response is massive cuts in staff and programs that damage quality and the effort to pursue the Triple Aim. President Biden is now up against a similar situation for the entire economy. We are rich now, but our wealth is fading into increasing inequity and deterioration of our infrastructure. We are not preparing for a sustained and improving future. Healthcare is only part of the problem, but it is the part that you and I touch. The next chapter will start with what should follow when you can “see” what is coming.