In August 2019, long before we were challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic The New York Times Magazine published “The 1619 Project.” We live in a time where race and the impact of our history of slavery, the era of Jim Crow, and the continuing struggle for social and economic equity for Black Americans will generate controversy for sure. Predictably, the project generated almost instant controversy which peaked with a letter to the New York Times from some well-known academics. The controversy was explained by Adam Serwer in The Atlantic. In trying to explain why several eminent historians wrote a letter of complaint to the editor of the New York Times about the project Sewer wrote:

Underlying each of the disagreements in the letter is not just a matter of historical fact but a conflict about whether Americans, from the Founders to the present day, are committed to the ideals they claim to revere. And while some of the critiques can be answered with historical facts, others are questions of interpretation grounded in perspective and experience.

Further along in the article Serwer writes:

The clash between the Times authors and their historian critics represents a fundamental disagreement over the trajectory of American society. Was America Founded as a slavocracy, and are current racial inequities the natural outgrowth of that? Or was America conceived in liberty, a nation haltingly redeeming itself through its founding principles? These are not simple questions to answer, because the nation’s pro-slavery and anti-slavery tendencies are so closely intertwined.

The letter is rooted in a vision of American history as a slow, uncertain march toward a more perfect union. The 1619 Project, and Hannah-Jones’s introductory essay, in particular, offer a darker vision of the nation, in which Americans have made less progress than they think, and in which black people continue to struggle indefinitely for rights they may never fully realize.

The Times responded to the criticism they received in a piece written by Jake Silverstein who is the editor of The New York Times Magazine where the articles were published. (If you clicked on “The 1619 Project” in the first paragraph you would have found a PDF of over 100 pages with a series of essays on many aspects of life in America including healthcare and the continuing impact of the legacy of slavery and racism.) In his defense of the project Silverstein wrote:

1619 is not a year that most Americans know as a notable date in our country’s history. Those who do are at most a tiny fraction of those who can tell you that 1776 is the year of our nation’s birth. What if, however, we were to tell you that the moment that the country’s defining contradictions first came into the world was in late August of 1619? That was when a ship arrived at Point Comfort in the British colony of Virginia, bearing a cargo of 20 to 30 enslaved Africans. Their arrival inaugurated a barbaric system of chattel slavery that would last for the next 250 years. This is sometimes referred to as the country’s original sin, but it is more than that: It is the country’s very origin.

Out of slavery — and the anti-black racism it required — grew nearly everything that has truly made America exceptional: its economic might, its industrial power, its electoral system, its diet, and popular music, the inequities of its public health and education, its astonishing penchant for violence, its income inequality, the example it sets for the world as a land of freedom and equality, its slang, its legal system, and the endemic racial fears and hatreds that continue to plague it to this day. The seeds of all that were planted long before our official birth date, in 1776, when the men known as our founders formally declared independence from Britain.

The goal of The 1619 Project is to reframe American history by considering what it would mean to regard 1619 as our nation’s birth year. Doing so requires us to place the consequences of slavery and the contributions of black Americans at the very center of the story we tell ourselves about who we are as a country.

I bolded most of the second paragraph because I think it is the position that generated most of the controversy from the historians. I am sure that the withering sense of inherited guilt that many white Americans gave evidence of this past summer when they joined in the Black Lives Matter demonstrations is more than balanced by a greater number of white Americans who don’t want to acknowledge the origin of their advantage and would prefer to continue to think that they earned and are entitled to all that they have. To suggest that they have enjoyed a distinct advantage all of their lives is just not something that they are interested in hearing.

One article in the publication that I have reviewed in the past, was “Why doesn’t the United States have universal health care? The answer has everything to do with race” was written by Jeneen Interlandi. She demonstrates that the four hundred years of white advantage is not only reflected in net worth and educational advantage, it is also reflected in life expectancy and access to healthcare. Manifestations of institutional and systemic racism and not genetic vulnerability to disease explains most of the variation in outcomes we see when we look at the differences in life expectancy, maternal/infant statistics, death rates from COVID-19, and in almost every disease if we bother to compare outcomes by race. Martin Luther King, Jr. knew the power of the deadly combination of racism and the poverty that is its offspring when he famously said:

“Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane”

Silverstein proceeds to a conclusion that many people, of whom those carrying Confederate battle flags are only the tip of the iceberg, will reflexly reject:

American history cannot be told truthfully without a clear vision of how inhuman and immoral the treatment of black Americans has been. By acknowledging this shameful history, by trying hard to understand its powerful influence on the present, perhaps we can prepare ourselves for a more just future.

That is the hope of this project.

In South Africa, after Nelson Mandela and the ANC came to power the country faced the injustices and crimes of its apartheid era with the “Truth and Reconciliation Commission.” The commission granted both amnesties for those who admitted the crimes they committed and reparations for those who had suffered the indignities of apartheid. The commission was an acknowledgment of the painful past and its impact on the present. Without acknowledgment, there would be no possibility for future peaceful coexistence. “The 1619 Project,” The Black Lives Matter movement, and the president’s calls for equity and racial justice in employment, education, housing, and healthcare seem to me like necessary steps in our efforts to begin to effectively address the issues that we bundle together as the social determinants of health. Without correcting the social determinants of health we are doomed to waste trillions of dollars on ineffective measures to improve healthcare for all and make progress toward the Triple Aim and sustainability of an affordable system of healthcare for all Americans.

In her remarkable 2018 book, These Truths: A History of The United States, Jill Lepore, a history professor at Harvard and frequent contributor to The New Yorker, made the same points that “The 1619 Project” made and placed her indictment in the context of many other excesses and abuses that we would prefer not to ponder. She wrote in a way that no other easily available account of our history has ever done before as she traced our national blight of racism all the way back to Christoper Columbus whose priest told him that his abuse of the indigenous people was wrong. Lepore reminds us of all the ways that slavery was justified when in fact it existed primarily as a mechanism for production. This is not the history I had been taught or could quote when in the eighth grade I won the DAR Medal for the best student in American History. It is a painful analysis for us to face at any age or at any time, but it is a problem that keeps making its presence known. In healthcare where we like to think that data should direct our search for improvements the amount of data that suggests that racism is a problem in healthcare is undeniable. Martin Luther King, Jr. knew understood the problem in 1965 and our data still says it is a problem.

If “The 1619 Project” and These Truths provide an accurate description of the history of race and its associated inequalities, Caste, The Origins of Our Discontents by Isabel Wilkerson goes beyond history and presents our dysfunctional social structure with a perspective that shows that racism and our structured society, which she argues is a true caste system, is a disease (my word not hers) that has an impact on everyone. If there has been any lesson to learn by observation from the pandemic, it is that what touches anyone can touch everyone. If you have not read Caste, Wilkerson presents a “Cliff Notes” version of her book in an article that was published in the New York Times Magazine last July and was updated this January.

Joe Biden knows that racism is a problem that touches all of us. His second executive order addressed the issue:

Executive order to promote racial equity

Biden ordered his government to conduct equity assessments of its agencies and reallocate resources to “advanc[e] equity for all, including people of color and others who have been historically underserved, marginalized, and adversely affected by persistent poverty and inequality.”

(Click on “ordered” to read the executive order in its entirety.)

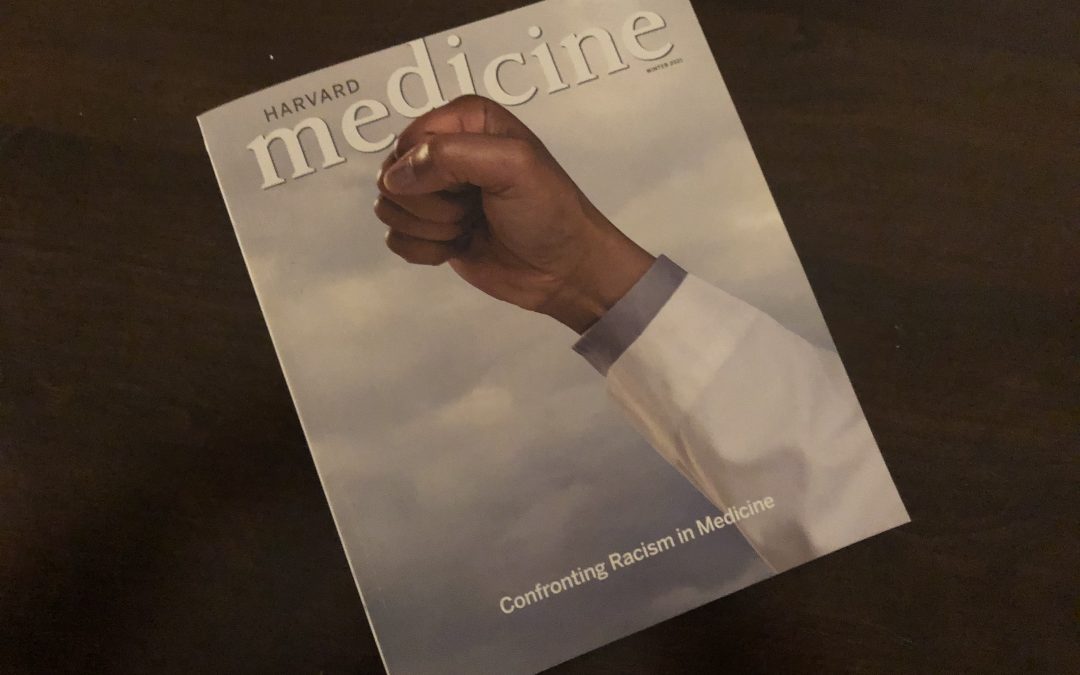

I am not sure when I received my copy of the Winter 2021 edition of Harvard Medicine which I found in a stack of magazines this week. The cover of the magazine is pictured in today’s header. Mixed in with all of the obituaries (I was pleased to see that none of my classmates have died recently) and the request for alumnae donations to the world’s richest medical school were several excellent articles that cover some of the same ground that Jeneen Interlandi had covered in her article in “The 1619 Project.” The lead article in the winter edition of Harvard Magazine was written by Stephanie Dutchen and is entitled “Field Correction: Race-based medicine, deeply embedded in clinical decision making, is being scrutinized and challenged.”

HMS has changed a lot since I graduated fifty years ago. Diversity was not an obvious objective of the admissions office at that time, though I sometimes joked that I was admitted as a Southerner from a state university to provide some diversity from New Yorkers who attended elite Northeastern colleges. As an aside, one of the small and poignant articles in the Winter 2021 Harvard Medicine is the story of Louis T. Wright who was admitted inadvertently to HMS in 1911. His application stated that he was a student at Clark University. Being parochial, the admissions office assumed that his excellent record was from Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. In fact, Wright was a student at Clark University in Atlanta, and he was an African American. After a review of the issues and an interview with a faculty member, Wright was admitted. He graduated fourth in his class and went on to have a distinguished career as a social activist, a surgeon in World War I, a productive researcher, and as an esteemed surgeon and leader in hospital administration at Harlem Hospital. He delivered a well-known address to the convention of the NAACP in 1935 that was entitled “Report on the Health of the Negro.” The article was written by Jesica Murphy and is entitled “A life as a physician, researcher, and administrator centered on challenging the inequities faced by Black people.” At the end of the article, we learn that things haven’t changed all that much in the 86 intervening years since 1935:

His report…addressed five areas affecting the health of Black people in the United States: housing, education, employment, the discrimination that Black patients and professionals face when using or working in medical facilities, and the discrimination that Black students face when applying to medical schools.

From the best I can count in my yearbook, my class had 18 women, two students of Asian descent, two Black students, and no Latinx or Native American classmates. The class that entered in 1967 had a hundred and forty members and by graduation, there were almost two hundred because of transfers from Dartmouth which was a two-year medical school at that time. I think that with the exception of a couple of women there was no additional diversity in the transfers. I distinctly remember references to racial differences presented in class and on the wards during medical school and my years of postgraduate training. In retrospect, as suggested in Dutchen’s article those statements were an expression of generally accepted biases and rarely were based on facts or science. I am sure that what I was taught had some impact on my practice. More importantly, what I was taught about “racial differences” was an expression of the biases that existed in the system in which I was embedded. The Dutchen article raises many questions and describes the processes by which the medical school is seeking to cast off its biases and help its students and all of healthcare begin to recognize the need for dramatic change. Things have not changed much, but for the moment a momentum toward change is developing. The momentum must be accelerated.

The Winter 2021 edition of Harvard Medicine is welcome evidence of change and increasing awareness of the structural inequities in our society. I was also pleased this week to discover that one of my favorite sources of thoughtful analysis, The Commonwealth Fund, is making race in medicine an area where they will be devoting resources. They have presented a new vision of equity, diversity, and inclusion. In the introduction they write:

The Commonwealth Fund has committed to becoming an antiracist organization. That commitment extends not only to our research agenda, our grantmaking, and our communications, but also to all aspects of our internal operations — from staffing and hiring practices to the management of our endowment.

The following statement expresses the Commonwealth Fund’s vision and pledge concerning promoting racial equity, diversity, and inclusion. To learn about our new research and grantmaking initiative to advance equity in U.S. health care, visit our Advancing Health Equity program page.

In the body of the statement they describe their vision:

VISION

The United States has long been marked by racism and discrimination. This legacy of inequity is also embedded in our health care system. It is evident in the profound disparities in health care access, delivery, and quality that adversely affect the health and well-being of Black Americans, Indigenous Americans, and people of color.

We as a foundation are conscious of our own role in the creation and perpetuation of these injustices. And we are committed to dismantling racism in health care.

The Commonwealth Fund envisions a health care system that values and benefits all people equally — one that combats racism and pursues equity, both in treatment and outcomes as well as in leadership and decision-making.

We believe achieving this goal requires an antiracist alliance of people and institutions across sectors of society. Only by working together can we recognize and value the lived experience of all individuals; ensure the delivery of compassionate, affordable, quality health care; and strive for equitable outcomes for all.

Please note that they are calling for an antiracist alliance of people and institutions across sectors of society. I take that as an invitation to all of us to participate in this effort to create a just society that will benefit both those who have been denied full participation for four hundred years and those of us who have benefited from that systematic denial.

The Commonwealth Fund could have stopped there but it went further. It articulated the specifics of what it pledged to do.

PLEDGE

The Commonwealth Fund is committed to an antiracist agenda. As we work toward our mission, we pledge the following:

- To expand and diversify the group of individuals and organizations whom we listen to, learn from, and support.

- To draw upon the Fund’s resources, history, and credibility in advancing the principle of antiracism and the goals of racial equity, diversity, and inclusion.

- To highlight and address structural and systemic inequities in U.S. health care through our grantmaking, intramural research, and dissemination activities so that the nation can achieve fair and just outcomes for people of color.

- To accelerate efforts within our own organization to cultivate a diverse and collaborative workplace, one where the life experiences and vantage points of every staff member are respected and valued, and where all staff can meaningfully contribute to the foundation’s work.

- To commit to concerted, sustained, and multifaceted action.

- To always be transparent in our actions and hold ourselves accountable for successes and failures in this endeavor.

I have been thinking about what I can do in the effort to promote equity, diversity, and inclusion. I wish that I was still in a leadership position. I did make some efforts to promote these ideals when I did have institutional influence, but I would have done even more had I known and better understood what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. called “the fierce urgency of now” when he eloquently spoke out about another moment of crisis and confusion for our nation, the war in Vietnam. If there was ever a time when we should collectively feel the fierce urgency of now it is now as we try to emerge into a fresh start with a new president and the hope that the pandemic may be behind us soon. The COVID pandemic and the brutal wave of police killings of Black Americans have shown a light on the negative impact of racism and caste and has produced compelling evidence that if America ever wants to live up to the image of opportunity, freedom, and justice that we try to present to the wider world, then there is a fierce urgency of now. Each of us must realize that we have a choice to apply our best efforts to being part of the solution, or continue by our silence and disinterest to be complicit in the continuing harm to individuals and collectively to all of us.

You might ask where do I start? Awareness of a problem is where we start a clinical journey toward healing. It will take you quite a while to read all of the links in this note, but if you did you would be well on your way to being prepared to participate where you live and where you work in searching for the solutions to our common problems that flow from racial inequities and our political divisions. Yes, I said common problems because we are a community and the pandemic has shown that we are connected and share in a common vulnerability even if we think there is a way we can be protected. The good news is that there is a common upside to engaging in the idea that 401 years is enough. There are better things possible for all of us. If you are a healthcare professional there is no need to look much further than where you work to join the process of building back better by addressing our national need for equity, diversity, and inclusion where you spend your time and have your greatest influence.