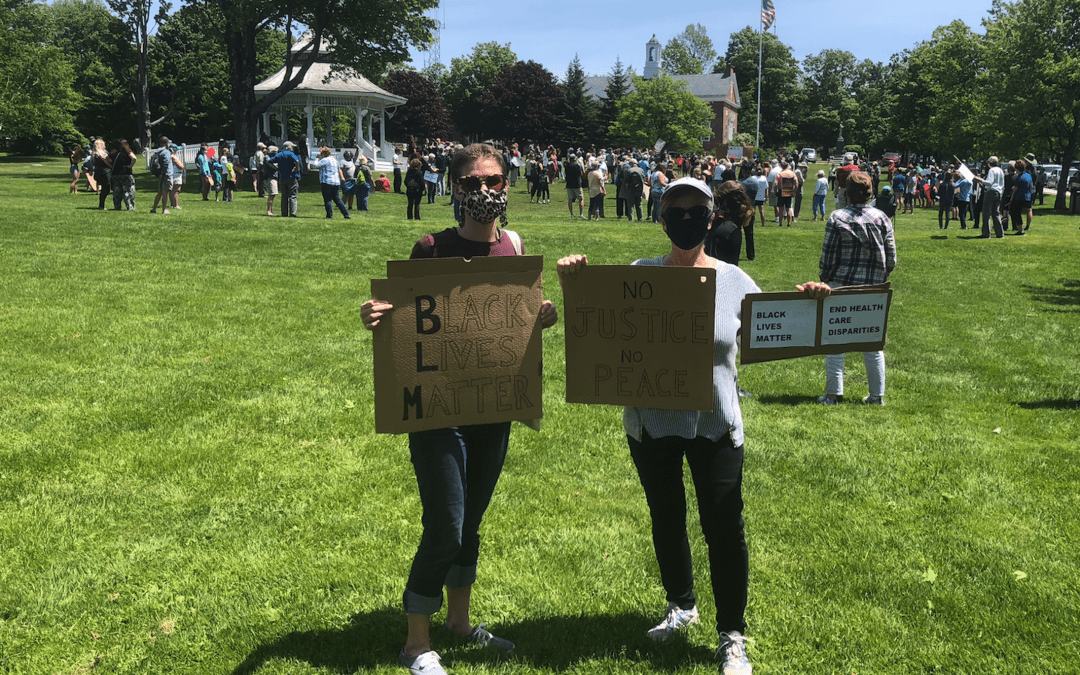

The header for this post should look familiar since last Friday’s post featured a very similar picture. The picture on last Friday had been taken on the previous Tuesday evening when about 200 people gathered on the New London Town Green to demonstrate their grief and anger that was generated by the torture and execution of George Floyd on a street in Minniapolis. The event was somber and subdued as I described:

Over 200 people showed up wearing masks and carrying signs. There were no speeches. A young man with a microphone announced that when the clock in the Baptist Church struck seven everyone was to stand in silence for nine minutes to reproduce the time that a knee was pressed against the neck of George Floyd. We were told that another bell would chime nine times when the nine minutes had passed. Nine minutes is a long time. When the time had passed there were a few quiet conversations, much like the ones that might occur as people exit a funeral, and then we went home with the hope that in some small way we had contributed to a growing awareness that the time had come to end all manifestations of racism and white privilege in our country.

I am sure that you have either participated in a similar sort of event or seen one on television. There have been thousands of events in every state and around the world in many countries. That fact alone makes this a unique time in history. Rarely have so many people in so many places gone to such lengths to express their concern about the same thing. So, it was not a huge surprise for me to hear that the event last Tuesday was not the last statement that my community would make.

At first I was surprised when I got an email saying that there would be a second demonstration yesterday at 1 PM, but then it occurred to me that not only would there be a second demonstration, there could be a third, a fourth, and many more. “This time” seems to be really different. The Black Lives Matter movement has begun to make a difference. In the past there would be demonstrations and maybe riots with burning and looting as an expression of anger and frustration over an event that underlined our problems with race, but in a few days, or a week at most, the flames would abate, some promises would be made, and things would return “to normal.” That’s not happening this time. This time the demonstrators are back everyday, most of the recent violence seems to be coming from the police, and there are no words of reconciliation or expressions of understanding coming from the president, his administration, or the leaders of his party. If anything, the president’s actions and the actions of some authorities have created further tensions. Another difference this time is that there have been many police, governors, mayors, and leaders of businesses who have stepped forward to express support for the meaningful changes. Can you believe that the NFL has apologized for its past positions on free speech?

We have all added to our fund of knowledge in 2020. All of us now know more about pandemics. Many are much more aware of the components of racial tension. Many more of us realize that unless we choose to move toward true equality of rights and work together to improve the economic disparities and healthcare disparities that we have perpetuated our free society and our personal freedoms will eventually disapear. All of us share a small planet that is under seige, and though some of us are more vulnerable, no one is without risk.

Our second rally drew more people than the first. There were at least 300 people who met on the Green yesterday, the two week anniversary of the murder of George Floyd. We heard a few speeches. Our most effective speaker was a young African American man who described his experience growing up in our town where he gradually realized that no matter how hard he tried his life in America would be different than the lives of his classmates just because he is black, and for no other legitimate reason.

There was a little bit of short lived confusion when a young man in a MAGA hat showed up with a sign that said: “BLM is a fraud!” He kept trying to stand between the crowd and the speakers, and was eventually joined by a buddy with a sign that said “Trump 2020: NO MORE BS.”

Despite the efforts of the two young men to create disruption, the speeches were delivered, and then the crowd marched off with homemade signs on an out and back 2.5 mile route down Main Street to the shopping center at the edge of town and back. Over the entire 2.5 mile march there was “call and response” and singing. Cars passing the marchers honked horns in support, and many drivers gave a thumbs up. Members of our local police were cordial as they accompanied the march on bicycles, and stopped traffic when the march crossed an intersection.The marchers were of all ages, and almost all were white. Wikipedia describes our lack of racial diversity:

The population was 4,397 at the 2010 census…As of the census of 2010, there were 4,397 people, 1,666 households, and 1,037 families residing in the town. There were 2,303 housing units, of which 637, or 27.7%, were vacant. 521 of the vacant units were for seasonal or recreational use. The racial makeup of the town was 96.5% white, 1.1% African American, 0.05% Native American, 1.1% Asian, 0.05% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, 0.1% some other race, and 1.2% from two or more races. 1.5% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

The activity was organized by local teenagers who were very vocal about the defects in the world they will inherit. It seemed to me as I thought about “why now” that we are at a strange intersection of a pandemic filled with uncertainty and risk and chronic racial conflicts that have been generating increasing energy like the energy created by the tension between tectonic plates in a faultline that is destined to result in an explosion that will create a change in the geography and topography of the landscape.

While the oppressive environment for minorities in America has increased under this administration, the pandemic has simultaneously underlined the economic and racial inequities in our society, and reduced our ability to function under stress. The first evidence of frustration that was waiting to explode was the appearance of white demonstrators armed with assault rifles and the symbols of white supremacy demanding from their governors an end to the “lockdown.” They made their case most dramatically on the steps of the capitals of Michigan and Wisconsin. Many people, myself included, felt vulnerable to their hostile stance, and the subsequent encouragement that the president offered them.

Intersectionality is a relatively new concept defined in the dictionary as:

…the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups.

[Kimberlé] Crenshaw introduced the theory of intersectionality, the idea that when it comes to thinking about how inequalities persist, categories like gender, race, and class are best understood as overlapping and mutually constitutive rather than isolated and distinct.

We now have a very complex society in which we can choose to become either more segmented and experience the increasing tensions associated with the complexity of our different experiences, or we can choose to increase our understanding and appreciation of our diversity and work together to make our different profiles and origins a strength rather than a continuing potential source of disruption.

I have been reading commentaries that point to the positive possibilities of this moment. There have been moments before in history when many people in many places became synchronized in their thoughts and actions, but it does not happen very often. One period of social synchronization in America was the Great Awakening of the 18th century. In the 1730s and 40s, Jonathan Edwards, a fiery preacher from Northampton, Massachusetts, initiated a movement that swept the country that was called “The Great Awakening.” It was a conservative religious reaction to the “Age of Reason” or “Enlightenment” that was sweeping Europe. I wonder now if we are on the verge of some other great awakening to the realities of how racism harms us all.

Social change in our country has often been initiated by the emergence of movements. The Abolitionist Movement, The Women’s Suffrage Movement, The Temperance Movement, The Civil Rights Movement of the 50s and 60s, the movement for the expanded rights and inclusion of the LGBTQ+ community, and the intermittent movements against gun violence, are all examples of attempts to use mass gatherings and collective actions to accomplish a step toward a progressive idea against the resistance of the status quo.

The examples above, with the exception of the abolition of slavery, eventually accomplished an objective without a war even though there were many moments of conflict, human suffering, deaths, and loss of property in the wake of demonstrations that erupted in violence bred of frustration or the push back by the power of the status quo. I see hope that this time we may be moving toward a lasting breakthrough. Two weeks ago we were all floundering in the uncertainty of the most devastating pandemic of the last one hundred years. Almost all of that uncertianty continues to exist, but it is remarkable how quickly we have set it aside as our attention has been drawn to the origin of another great source of suffering, racism in our divided society. Most of the movements mentioned above have been about inclusion of more people in some form of human rights. We are moving away from the privaleges of a dominant race toward the universal application of human rights. How far have we come and how near to the moment are we when everyone will be able to enjoy an equal share of freedom and opportunity? When will the speech I heard from the young black man about growing up in New London will be different?

What seems true about most of the movements is that the status quo which they seek to disrupt is beneficial to the group resisting change, and detrimental to the group asking for change. The demonstrations are exercises that attempt to initiate the redistribution of power. Frequently, long periods of debate like the conversations of the abolishonists or of the proponents for gay marriage gradually spread awareness that achieves a difficult objective that is seeded by rhetoric and accomplished by a crescendo of unusual or unexpected events. Is that what we have seen with the awareness of the differential vulnerability of African Americans and other minorities to COVID-19 then multiplied by the unavoidable visual awareness of the brutality of the death of George Floyd?

I read a great description of this moment in the newsletter that comes from The Atlantic which I think has done a great job of both explaining and following the pandemic, and analyzing the reactions to the death of George Floyd.

Caroline Mimbs Nyce writes in a piece entitled, “The Protests Meet the Pandemic: Neither appears to be abating. Today, we’re examining where they intersect”:

The town square has come roaring back to life.

The anti-racism movement, set off by the death of George Floyd, is enormous in scale. This past Saturday, more than 400 protests took place in America alone, with dozens more overseas. Streets once silenced by the coronavirus outbreak are filled with the cacophony of collective action.

In tandem, the pandemic rages on, with some states reporting their highest numbers yet. “There’s no point in denying the obvious,” Alexis C. Madrigal and Robinson Meyer, who helped build the COVID Tracking Project, write: Protesting raises the risk of transmission. That risk itself is further “complicated by, and intertwined with, the urgent moral stakes.”

In a companion article entitled “America Is Giving Up on the Pandemic: Businesses are reopening. Protests are erupting nationwide. But the virus isn’t done with us” written by Alexis Madrigal and Robinson Meyer, the tension and jeopardy of the moment is succinctly described:

“Businesses are reopening. Protests are erupting nationwide. But the virus isn’t done with us.”

They go on to say:

The risk of transmission is complicated by, and intertwined with, the urgent moral stakes: Systemic racism suffuses the United States. The mortality gap between black and white people persists. People born in zip codes mere miles from one another might have life-expectancy gaps of 10 or even 20 years. Two racial inequities meet in this week’s protests: one, a pandemic in which black people are dying at nearly twice their proportion of the population, according to racial data compiled by the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic; and two, antiblack police brutality, with its long American history and intensifying militarization.

It is a trifecta plus more. We have combined healthcare disparities with a pandemic, extended it with the most disgusting and undeniable display of police brutality toward one individual, and made it a national cause through the demonstrations that demand for far reaching change. The plus is the way a perverted system of “law and order” responds to public demonstrations with excessive force as a demonstration and revelation of its embrace of authoritarian practices.

There are ample reasons for more and more public displays of multiracial resolve that now is the time for change. No one knows how the COVID-19 pandemic will evolve and end, and no one knows how the demonstrations will end, or what they will ultimately accomplish, but I was encouraged this week as I listened to a conversation between Ezra Klein of Vox and Ta-Nehisi Coates, the very wide ranging voice of black reason, who has given us so many interesting books and articles on the experience of being black in America. Perhaps his best known work is the moving letter to his son, Between The World and Me, about the hazards of being black in an oppressive America. It was his literary presentation of “the talk” that many black parents give their sons as they come of age.

In the past Coates has expressed his skepticism about black Americans ever making progress against the forces of racism in America so I was very surprised by the major take away from the interview. He now has reason to hope. Klein writes:

The first question I asked Ta-Nehisi Coates during our recent conversation on The Ezra Klein Show was broad: What does he see right now, as he looks out at the country?

“I can’t believe I’m gonna say this,” he replied, “but I see hope. I see progress right now.”

In the Vox article that is an exerpted transcript from the interview Klein continues:

But there’s one particular thread of this conversation that I haven’t been able to put down: There is now, as there always is amid protests, a loud call for the protesters to follow the principles of nonviolence. And that call, as Coates says, comes from people who neither practice nor heed nonviolence in their own lives. But what if we turned that conversation around? What would it mean to build the state around principles of nonviolence, rather than reserving that exacting standard for those harmed by the state?

That thought is worth considering now as there all calls for abolishing or redirecting the police. I will end this piece by saying if we can find the courage and wisdom to redefine how the police contribute to order and safety for all people in our society, why stop there? Let’s also “awaken to the positive benefits for all of a redesign of healthcare to eliminate its disparities, and why stop there? Why not provide every child with the education that will prepare them to be contributors to a better future, and why stop there? Why not be sure that everyone has a place to live and a nourishing diet, and why stop there? Why not use our wealth and experience to bring all of the benefits of a free and open society to the whole world? It is grandiose thinking, but it is more wholesome than the president’s calls for “domination.”

There have been dreamers who have said it could be possible to make things better for everyone. Who knows? If a skeptic like Coates can see the possibilities, perhaps there is hope for all of us. Would it not be wonderful to imagine us to be standing together at the doorway of a Great Awakening to the possibilities inherent in caring about one another?

Great article Gene. I love promoting the idea that 2020 might be the spectacular year we’ve been waiting for.

I saw this poem – it reminded me of your article.

—-

What if 2020 isn’t canceled?

What if 2020 is the year we’ve been wait for?

A year so uncomfortable, so scary, so raw – that it finally forces us to grow.

A year that screams so loud, finally awakening us from our ignorant slumber.

The year we finally accept the need for change.

Declare change. Work for change. Become the change.

A year we finally band together, instead of pushing each other further apart.

2020 isn’t canceled, but rather it is the most important year of all.

– Leslie Dwight