May 8, 2020

Dear Interested Readers,

It’s a Time for Humility, Caution and Focus on Long Term Improvements. It is Not a Time for Arrogance, Abandon, and the Pursuit of Short Term Gains.

It’s hard to know what everyone is thinking, and as a result what is likely to be the sum of all those independent thoughts and the actions that flow from each of us doing what we think is best. The easy road is behind us. For the last seven weeks we have been told what to do, and an amazing number of us have followed directions. Sure, there are still some independent souls among us, like the president and the vice president, who have put individual comfort and convenience ahead of the collective benefit of the community, but what I see in my little town and the reports that are available on the news and social media suggests that most of us are following the advice and direction of our national experts, most prominently, Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Most of us have believed Dr. Fauci and not the president when he has said that social distancing and face masks were our best strategy. He has told us we are not doing enough testing. He has tried to infer that in many places we are not ready to move toward normal activities. He has told us to expect 100,000 to 200,000 deaths. He has told us that there is no evidence that the virus escaped from a Wuhan lab or was manufactured by the Chinese. He has told us that Plaquenil is not a miracle drug. He has served us well as a foil for the misinformation that the president offers as he gives us his best imitation of a paranoid snake oil salesman.

If you have not noticed, it’s beginning to look like the president is becoming unraveled. Nicholas Kristof described the scene in a column this week entitled “The Virus Is Winning: Magical thinking won’t protect us.” Before going further, I should remind you that “magical thinking” isn’t a cute word play. It has clinical significance and is frequently seen in the construction of irrational thought in various forms of mental illness. A psychiatry mentor once told me the difference between the thought processes of a sane person with a neurosis, and an unbalanced individual with a psychosis. The neurotic knows that 2 plus 2 is 4, but he is worried about it. The psychotic individual believes that 2 plus 2 is five and has a line of reasoning to prove it. Often the explanation for the creative math includes some “magical thinking” or some sort of conspiracy. Kristof writes:

The White House plan to disband the task force is in characteristic disarray, with President Trump reversing course on Wednesday and saying that the task force would continue but change its focus. The confusion perfectly reflects the incoherence of the American “strategy” toward Covid-19.

Vice President Mike Pence had earlier said that the disbanding of the task force was possible because of “the tremendous progress we’ve made” against the virus.

Hmm. It’s actually the virus that has made tremendous progress, eclipsing heart disease to become the No. 1 cause of death in the United States. In less than two months, we have lost more Americans to the coronavirus than in the Vietnam, Persian Gulf, Afghanistan and Iraq wars combined…

Even the small decline in new cases in the United States is misleading, for it’s simply a result of great progress in the New York City metropolitan area. Exclude New York and new cases in the United States are still increasing.

It is true that in many of the states where people are beginning to go back to work none of the criteria that have been established by the most permissive of the voices trying to articulate a way back to “normal” commerce have been met. The experts are predicting that the virus which is not flawed by magical thinking, and is not concerned about the economy or the impact of the economy on the president’s likelihood of being re-elected will just do what a virus does and keep hoping around to any available host, and there are plenty of those everywhere. It is true that we have had 1,256,842 confirmed cases in the U.S and 75,658 deaths as of 9:30 PM last night, May 7. What is magical thinking is that the number won’t continue to rise even faster as we get back to business. Without a strategy for coordinated testing with follow up and isolation of contacts there is little to suggest that there is anything ahead for us but more of what we have seen in New York, Boston, Chicago, and Detroit, and are now seeing in LA.

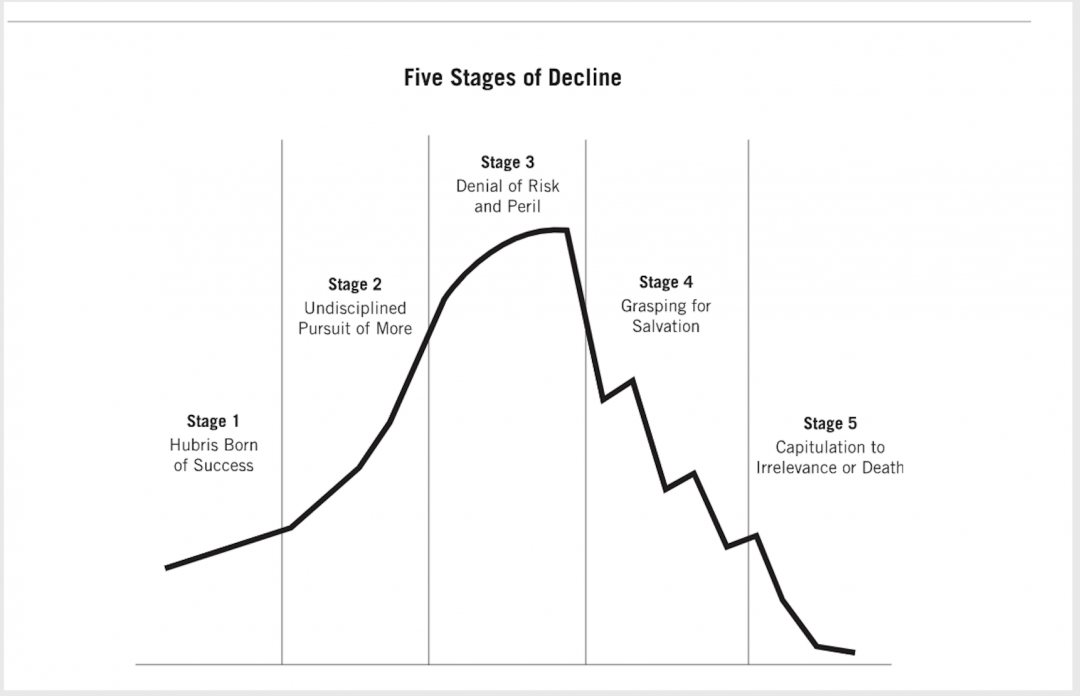

I am reminded of the analysis in what may be the most useful general business book I ever read. It was written by Jim Collins. How the Mighty Fall is not nearly as famous as Good to Great or Built to Last, but it tells a story that we need to review frequently. On his website, Collins describes the concept in one paragraph:

Five Stages of Decline is a concept developed in the book How the Mighty Fall. Every institution is vulnerable to decline, no matter how great. We found that great companies often fall in five stages: 1) Hubris Born of Success, 2) Undisciplined Pursuit of More, 3) Denial of Risk and Peril, 4) Grasping for Salvation, and 5) Capitulation to Irrelevance or Death. Institutions can be sick on the inside and yet still look strong on the outside; decline can sneak up on you, and then—seemingly all of a sudden—you’re in big trouble.

Did you catch the phrase ‘ Institutions can be sick on the inside and yet still look strong on the outside…” ? I think, given the fact that so many were eager to elect a “businessman” as our president, it is justifiable to exchange “institution” in the second sentence for “nation.” The sentence would then read:

Every nation is vulnerable to decline, no matter how great.

What follows then nicely matches our experience with this president. He came preloaded with arrogance which is some sort of “hubris.” Without him we have had plenty of arrogance for a long time. Many in our nation were delighted when like Ronald Regan before him, he told them that they were wonderful and that all that was wrong was the result of the evil intent of others like illegal aliens and the purveyors of fake news. Rather than pay attention to the deteriorating infrastructure of the nation, the rape of the environment, and the manifest inequality that has relegated many to a modern day form of servitude, he led the charge forward supported by his enablers in the Senate toward the destruction of the flimsy social safety net we had, the undermining of the ACA, and the passage of the unconscionable Tax Act of 2017. The thermometer that measured the success of this strategy of “more” manifested by the transfer of huge amounts of wealth to those who did not need it at the expense of America’s stability and future is the stock market, The public’s and the president’s obsession with the Dow Jones average as a measure of his genius and our collective superiority is proof that we have matched the second step of Collins’ formula for failure.

In the book, Collins emphasizes that it is the external world, and not internal genius, that usually is the defining force in what happens next. COVID-19 is an external risk and peril that the president claims to have managed perfectly against all evidence that he failed to appreciate the threat and disregarded the advice of those who tried to point out the threat. But, we know that is not true. He has talked ragtime in front of cameras so often over the last two months that it’s hard to deny that he has waffled between unrealistic denial and weak compliance with the advice of experts. His comments this week that he was disbanding the COVID-19 task force, and then a day latter saying that he wasn’t, is a perfect example of his great talent of playing both ends against the middle. It is more likely that he makes a decision then doubts it when someone points out the flaws in his reasoning. Nevertheless, he has been blessed up to now as the prince of having it both ways. Tom Friedman, in a piece this week entitled “Make America Immune Again: Many sources of the nation’s strength have eroded” has emphasized that the president can manipulate the press and the public, but he can’t manipulate mother nature, and what she can throw at us like hurricanes and viruses. A facade of success that covers deeply rooted problems will not hold up under stress. “We’re going to win so much, you will get tired of winning” sounded great to many in 2016. Now many of his famous “base” are among the 33 million who are trying to get through defective phone and computer systems to register for unemployment benefits.

By the Collins formula, the president is at stage four, “grasping for salvation.” The premature return to business without testing and without the data demonstrating that the storm has really passed is more likely to look like a fool hardy, self serving move of desperation some time a few weeks or months in the future, than a stroke of genius. It is a political “hail Mary pass” and he is no Doug Flutie. If Gerald Phelan had dropped the pass there would have been little lost. It was just the last play of an exciting game. There have been many hail Mary passes in football, and most are dropped. There are many “hail Mary” passes in business, and as Collins reports, these acts of institutional desperation generally fail. Say, “Bye Bye,” to Neiman Marcus and J. Crew. With the lack of coordination across the country, the lack of appropriate testing, and the lack of contact follow up, this “hail Mary” will be followed by many people receiving “last rites.”

The Collins formula breaks down at stage five, Capitulation to Irrelevance or Death. In business the residual assets are liquidated, and another mismanaged corporation joins TWA, Pan AM, Eastman Kodak, Computer City, BlockBuster, Sears, and on and on in the ignominious dustbin of business failure. The nation will not go away like these failed enterprises, but it will be damaged in a way that will have continuing consequences. There will be no death, and we will still have relevance, but we will have had many painful individual losses, and collectively we will have lost ground on our difficult road toward “these truths.”

Collins never completely extinguishes hope for an institution. Those companies that survive have leaders who stop fooling themselves and stop denying reality. They wake up to their peril and recognize their internal inadequacies and fix them before sliding into desperate moves with low probabilities for success. They give up on magical thinking and start using metrics. They make hard decisions. Our hope lies in the good sense of a majority of individuals, and the fact that there are some leaders in science and state governments who recognize that reason and a willingness to do the hard things for as long as reason dictates is the best way to minimize further losses. It has been shown that a majority of Americans from both parties are very apprehensive about the reopening of the economy. New York’s governor, Andrew Cuomo, says that the question is not when, but how. Jennifer Rubin, writing in the Washington Post this week, described Cuomo’s reasoning:

“Our position in New York is the answer to the question, how do we reopen, is by following facts and data as opposed to emotion and politics. Right?” He added, “You can calibrate by the number of hospitalizations, the infection rate, the number of deaths, the percentage of hospital capacity, the percentage that you’re finding on antibody tests, the percentage of finding on diagnostic tests, positive, negative. You’re collecting tracing data, make your decisions based on the information and the data.” He said the proof is in the numbers: New York’s cases and deaths are declining as the rest of the country’s increases.

To refine Cuomo’s point, the issue is not if we reopen but whether we open stupidly, with reckless disregard for human life, or as carefully as possible, driven by the data, so as to avoid unnecessary death and human suffering. This points to the great malfeasance by red-state governors, who could achieve the same ends (restarting the economy) without great loss of life if they did this intelligently. They choose not to because they choose not to lead, to communicate the stakes and to act responsibly.

That may sound blunt, but it is time to be blunt. I have quoted from Jeffrey Kruger’s book, The Narcissist Next Door (2014), before. I have discovered a three minute YouTube clip from a presentation Kruger gave in 2015. In the book he presents Donald Trump as a great example of the most malignant form of narcissism. In his talk he doesn’t name the president, but the description is there. Narcissists can “charm your pants off” but it always ends badly because they lack empathy, and in the end the only thing that is important is their self interest. I think we have feared for a long time that it was not going to end well with Donald. The question that comes up next is what are we going to do when all of this passes.

Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal gives us the first step of “recovery” in an OP Ed piece in the New York Times this week. Dr. Rosenthal, who is the editor of the Kaiser News Service, former New York Times staff writer, former EW physician, and the author of American Sickness, implied that the first step in our recovery is to recognize how we failed. Her piece was entitled, “We Knew the Coronavirus Was Coming, Yet We Failed: The vulnerabilities that Covid-19 has revealed were a predictable outgrowth of our market-based health care system.” She is not blaming it all on Trump. It took us decades to prepare to be as vulnerable as we were. We focused more on finance than on preparing to meet the needs of the nation:

Our system requires every player — from insurers to hospitals to the pharmaceutical industry to doctors — be financially self-sustaining, to have a profitable business model. As such it excels at expensive specialty care. But there’s no return on investment in being primed and positioned for the possibility of a once-in-a-lifetime pandemic.

Combine that with an administration unwilling to intervene to force businesses to act en masse to resolve a public health crisis like this, and you get what we got: a messy, uncoordinated under-response, defined by shortages and finger-pointing.

No institutional players — not hospitals, not manufacturers of ventilators, masks, tests or drugs — saw it as their place to address the Covid-19 train coming down the tracks.

After a clear description of the problem she offers an analysis:

In our market-based system, hospitals are primed to compete, not coordinate. They compete for patients who need lucrative procedures and for ratings in magazines like U.S. News & World Report. While legally they have to treat anyone who turns up in the emergency room, they are not eager to treat infectious diseases like Covid-19, which disproportionately hits people with poor insurance and carries a stigma….

…the Covid-19 stress test has laid bare a market that is broken, lacking the ability to attend to the public health at a time of desperate need and with a government unwilling — in some ways unable — to force it to do so. This time around, thousands of stalwart medical professionals have answered the call to treat the ill, doing their best to plug the longstanding holes that the pandemic has revealed.

Whether it’s regulated or run by the government, or motivated by new incentives, the system we need is one that responds more to illness and less to profits.

I offer Dr. Rosenthal’s thoughts as prep for Dr. Sidhartha Mukherjee’s recent New Yorker article. He says much the same things, but at greater length and with more concrete examples. The title of his article is essentially a summary of what he has to say. “What the Coronavirus Crisis Reveals About American Medicine: Medicine is a system for delivering care and support; it’s also a system of information, quality control, and lab science. All need fixing.” You may know Dr. Mukherjee as the oncologist who wrote the 2010 best seller, THE EMPEROR OF ALL MALADIES: A Biography of Cancer.

If you follow the link to the New Yorker article you will discover that there is an audio version. I highly recommend it as a companion for a brisk three mile walk. Like Dr. Rosenthal, Dr. Mukherjee mines this moment for the insights we will need for the new world that he hopes will follow our recovery from the pandemic. Neither physician/author has a desire to return to the world that failed us.

Dr. Mukherjee begins with the story of how the factory of a company that supplied a “P valve,” a small, but critical $10 part that was in every Toyota burned to the ground one night in 1997. Since Toyota practiced “just in time (JIT)” production they were immediately at risk of having their assembly lines brought to an immediate halt. The fire had revealed that their production system had no “resilience.” The focus on efficiency had produced a hidden liability that it took a disaster to reveal. Toyota is a focused problem solver. In three days they had recruited several independent companies and taught them how to make “P valves.”

Over the next six pages Mukherjee gives us story after story that demonstrate the lack of resilience in American medicine. Our Achilles heel is not just our inability to make enough N 95 protective masks. The way we have structured healthcare to be a system driven by finance has cost us the ability to be resilient when faced with a sudden acute need. We approach research with a very short attention span. He points out that our EMR, especially Epic, is not designed to help manage individual patients or populations of patients as much as it is able to generate revenue through substantiating RVU counts for billing. We were ill prepared to generate or approve tests as part of an anticipatory strategy. Our NIH, CDC and FDA are encumbered by all of the liabilities of a bureaucracy. In essence, our system of care was built to maximize profit in the private sector while reducing taxes. It was supervised by an underfunded and unresponsive regulator system. Together with publicly funded research programs that have a short attention span the COVID-19 challenge has shown that we have an expensive system of care that can’t protect the health of the nation. After building his case against the status quo through the testimonies and stories of many manufacturers, frustrated researchers, and disillusioned clinicians, he sums up our plight:

When the tide goes out,” Warren Buffett once said, “you discover who has been swimming naked.” The pandemic has been merciless in what it has exposed. In many cases, the weaknesses in our medical system were ones that had already been the subject of widespread attention, such as the national scandal of health-care coverage that leaves millions of Americans uninsured. In others, they should have been the subject of widespread attention, because we had plenty of warning. Again and again, in the past several weeks, we’ve heard of shortages—shortages of protective gear, of ventilators, of pharmaceuticals. Yet, even before the crisis, medicine was dealing with troubling scarcities of needed drugs and support systems.

He is relentless. A little further along he writes:

As such pre-pandemic stories proliferate, they point toward more fundamental reckonings. Leave aside the tragedies of those who died alone in isolation rooms in hospitals, or of the disproportionate disease burden borne by African-Americans and working-class immigrants. Leave aside the windblown avenues of an empty, joyless city, the generation-defining joblessness that has shifted so many from precarity to outright peril. To what extent did the market-driven, efficiency-obsessed culture of hospital administration contribute to the crisis? Questions about “best practices” in management have become questions about best practices in public health. The numbers in the bean counter’s ledger are now body counts in a morgue.

I will add that when you take a system that has been directed for decades toward maximizing shareholder value and building margins in theoretically eleemosynary institutions, mix in a pathetically inadequate and self absorbed president, and add a potent new virus, what you get is a crippled economy and the likelihood of many months of continuing pain and continued suffering manifested as human illness and death with associated economic collapse. The neglected need to improve the social determinants of health has morphed into the necessity of social distancing for survival since unlike South Korea we do not really have the testing capability or the case follow up machinery to control the further spread of the virus. The virus has infected over a million people and this far has killed at least 75,000 people directly and indirectly has probably taken many more, but it still has over 320 million potential bodies to infect and very little organized resistance.

Mukherjee does not want us to return to a deficient “normal” that lacks resilience. He finishes by saying:

“Recovery” is the word of the moment; it connotes a return to a previous state of well-being. For many patients with chronic conditions, though, treatment aims not to restore a baseline of precarious health but to reach a higher baseline. Some of medicine’s frailties are new; some are of long standing. But what the pandemic has exposed—call the experience a stress test, a biopsy, or a full-body CT scan—is painfully clear. Medicine needs to do more than recover; it needs to get better.

My advice for the moment is that no matter what your governor or the president says that you can do, be sure that you keep protecting yourself by practicing social distancing. I can forgo at least another three months of haircuts before my hair is as long as it was in the early seventies when Dr. Eugene Braunwald, Chief of Medicine at the Brigham and the Hersey Professor of the Theory and Practice of Physic at Harvard Medical School, sternly observed to me at “morning report” that I looked like a hippie. I am down a few pounds from avoiding restaurants. I would love to see my grandchildren, but not traveling to see them this summer may mean that I will live to see them finish high school or perhaps someday attend their weddings. But, most of all I want them to live in a country that has learned some painful lessons. The greatest tragedy would be for all of this suffering and sacrifice to be lost because of a collective inability to recognize that we have nothing if we can’t pursue “these truths” for the “least of these, my brethren.” Like it or not, just as shrouds have no pockets, death comes to all eventually. Our collective challenge is to improve the journey through life for everyone because if anyone suffers we are all at risk in the real world of viruses where magical thinking protects no one.

A Different Close

In this part of the letter you expect me to extol the beauty of my environs and suggest that you be sure to take advantage of some outdoor activity while I tell you about the picture at the top of the page. I had every intention of doing that this week. I am a creature of habit who is slow to make process changes.

As you can see, the header does come from a recent drone video made by my very creative neighbor, Peter Bloch. The video from which I took the screenshot was produced this week. Peter called it “Sunset Over Little Sunapee.” If you click on the link you can see the whole video. It is a very pleasant two minute journey that was recorded from “The Ledges” a highpoint that offers great views from the northeast end of the lake.

As I began to think about hiking up to “The Ledges” which is something that I have never done, I realized how lucky I was to live in a place where I can be out and about without much fear. As I thought about my good fortune more, I began to feel a little guilt thinking of the misery in Boston just two hours south, and then the greater misery six hours away in New York. Perhaps my thoughts were distorted by the two articles in the New Yorker that immediately follow Dr. Mukhurjee’s article. The first is “April 15, 2020: Twenty-four hours at the epicenter” which contains alarming pictures of empty streets in the usually busy city. The second article is a “portfolio” of pictures taken by a Lenox Hill Hospital nurse of her friend, another Lenox Hill nurse, with an introduction written by David Remnick, the editor of the magazine. The grief and suffering counterbalanced by dedication, bravery, strength, and fatigue revealed by these photographs is startling and worth your attention. I fear that there will be many unknown acts of professional courage and commitment that will be thrown away by those who are more concerned about dollars than deaths. Remnick ends his comments with a quote from Cady Chaplin who is the nurse in the pictures:

Many evenings, at seven, Chaplin can hear the cheering and honking, the nightly tribute to the “essential workers” who are keeping the city alive. The sound often makes her tear up with gratitude, but she is wary when she hears platitudes about the “heroic” work of health-care professionals. She doesn’t want to be glorified all of a sudden. “This is what we trained to do,” she says. “This is what we do. That was true a year ago, and it will be true a year from now.”

Be well! Practice social distancing. Wash your hands frequently. Don’t touch your face. Cover your cough. Stay home unless you are an essential provider. Follow the advice of our experts. Assist your neighbor when there is a need you can meet. Demand leadership that is thoughtful, truthful, capable, and inclusive. Let me hear from you often, and don’t let anything keep you from doing the good that you can do every day,

Gene