Perhaps the most satisfying part of writing is hearing from you. This week I was delighted to hear from two people for whom I have great respect and some past history. One letter was a discussion of what faces us now; how and when to move toward more normal business activity and away from social distancing. The truth is that no one knows those answer for sure. The question about how to return to normal has become the question that is behind much of the news reporting and analysis of the past week. It is quickly becoming a political question. I see it as a question that also measures our collective ability to endure a hardship in order to achieve a difficult objective.

Based on two recent news reports, one about COVID-19 patients who do not look sick having asymptomatic low O2 sats, and another report suggesting that increased respiratory rates are an early warning of COVID infection, one of the people who wrote to me asked if this information could be a game changer “now” that could make moving toward normal activity safer. My quick answer was I don’t think so, but these observations do provide clinically useful insights that might be helpful in reducing the mortality of COVID-19 infections, or as some people have begun to say, C-19. The second letter was a question asks about “when.” “When” is uplifting because it begins the phrase “when this is over.”

Either letter could have been more than enough to keep me busy thinking and writing for hours, but together there is an interesting perspective on how we get through this challenge that should be uniting us in a common objective. We all know that the “treatment” has been, and continues to be very difficult. Some of us, especially in some southern and midwestern states, have had enough. The pains of separation, loss, and economic uncertainty have made many of our citizens angry, and they have taken to the streets with the bizarre encouragement of a president who shares their inability to tolerate uncertainty and delayed gratification. Without effective trustworthy leadership any possible fantasy or conspiracy finds an enraged audience, and has an aura of authority that arises from “some people say.” It seems hard for many to accept factual statements from rational physicians like Dr. Anthony Fauci who might say, “Nobody knows for sure, but our best science suggests…” We must get through the uncertainty and ambiguity of “now” to get to the opportunities of “when.”

“When” assumes with certainty that the day will come when C-19 and our associated individual and collective miseries will be history. Whether that moment is achieved by a triumph of science, or whether the storm just passes as tens of thousands of bodies lie in its wake, as happened with the “Spanish Flu” a hundred years ago, is yet to be determined. No matter what happens, there will be a moment “when” the stresses of this moment will be behind us. The letter from my other friend about “when” begins with the assumption that there is opportunity in whatever “new normal” exists when “when” arrives and the angst of “now” is over.

The first letter began:

Hi Gene,

You’ve been doing a great job with your blog, in the midst of these troubled times!

In case you didn’t see it, I am attaching a very interesting article in today’s NYT that describes how COVID19 induces hypoxia and recommends the use of a pulse oximeter as a low-cost route to early identification of COVID pneumonia. One of the striking findings in the article is that the normal signal of breathing problems (a build-up of CO2) doesn’t happen with COVID-19, so that hypoxia can progress quite far, without the person realizing that anything is wrong – hence the value of proactive monitoring of blood oxygen levels. I am also attaching an earlier article about a small start-up venture, WHOOP, with a ‘smart’ wristband, that has been successful at early identification of COVID-19 through observations of increased respiratory rates, a corollary of the hypoxia.

He had much more to say, but let’s look at the articles first. The New York Times opinion piece he refers to was written by Richard Levitan, an experienced EW physician from New Hampshire, who volunteered for ten days at Bellevue where he had been trained. It is entitled, The Infection That’s Silently Killing Coronavirus Patients: This is what I learned during 10 days of treating Covid pneumonia at Bellevue Hospital.

Dr. Levitan points out that many people who are very ill as demonstrated by extremely low O2 sats look better than they are. Here is his description:

We are just beginning to recognize that Covid pneumonia initially causes a form of oxygen deprivation we call “silent hypoxia” — “silent” because of its insidious, hard-to-detect nature.

Pneumonia is an infection of the lungs in which the air sacs fill with fluid or pus. Normally, patients develop chest discomfort, pain with breathing and other breathing problems. But when Covid pneumonia first strikes, patients don’t feel short of breath, even as their oxygen levels fall. And by the time they do, they have alarmingly low oxygen levels and moderate-to-severe pneumonia (as seen on chest X-rays). Normal oxygen saturation for most persons at sea level is 94 percent to 100 percent; Covid pneumonia patients I saw had oxygen saturations as low as 50 percent.

To my amazement, most patients I saw said they had been sick for a week or so with fever, cough, upset stomach and fatigue, but they only became short of breath the day they came to the hospital. Their pneumonia had clearly been going on for days, but by the time they felt they had to go to the hospital, they were often already in critical condition.

He gives us the proposed explanation:

We are only just beginning to understand why this is so. The coronavirus attacks lung cells that make surfactant. This substance helps keep the air sacs in the lungs stay open between breaths and is critical to normal lung function. As the inflammation from Covid pneumonia starts, it causes the air sacs to collapse, and oxygen levels fall. Yet the lungs initially remain “compliant,” not yet stiff or heavy with fluid. This means patients can still expel carbon dioxide — and without a buildup of carbon dioxide, patients do not feel short of breath.

The second article that my friend references is from Boston.com. It was about a fitness device, Whoop. The report was entitled, “By detecting early signs, Boston fitness tracking company WHOOP says it’s helping further COVID-19 research.” The article discusses how the precise tracking of respiratory rates, which was originally designed to guide physical training, can indicate an oncoming respiratory illness. Pulse oximeters and WHOOP devices are easy to obtain in the market. My friend asked a very insightful question. If we had widespread use of these devices, would we be able to return to business as usual sooner because we would know when people became infected and needed help sooner. He posited that earlier detection supported by these devices might help limit spread of the virus, and decrease the number of people who needed ICU support so that we would remain within the capacity of our hospital resources.

I wrote him a long response which I will present to you in an edited form:

I find a lot to think about in Dr Levitan’s article. He is absolutely right about the fact that in healthy people the stimulus to breathe is to get rid of CO2, and not what most people would think it is, low O2 levels. This is an important fact because there are classes of lung patients who have rising levels of CO2 which makes them get worse and sometimes die if they are given oxygen without great precautions.

Measuring O2 sat is easy. I don’t think the Whoop device measures O2 sat, but it is true that there is a rough correlation between O2 sat and the respiratory rate. Unfortunately respiratory rate elevation is not nearly as specific for sickness as is a low O2 sat. Anxiety alone will raise respiratory rates. In medicine we talk about tests that are sensitive, but not specific. There are cheap pulse oximeters that are available and connect to a cell phone that would allow transmission of results to a healthcare system.

I had a few patients to whom we gave devices that just reported O2 sat and pulse rate, but did not “connect.” They were helpful in managing some patients with CHF. There is …literature that points out that unnoticed respiratory events and changes in pulmonary mechanics can presage episodes of heart failure. It seems that we are smart enough to invent a lot of good things, but we are inept at organizing the products in a useful way….Atul Gawande has said that once we were ignorant, now we are inept.

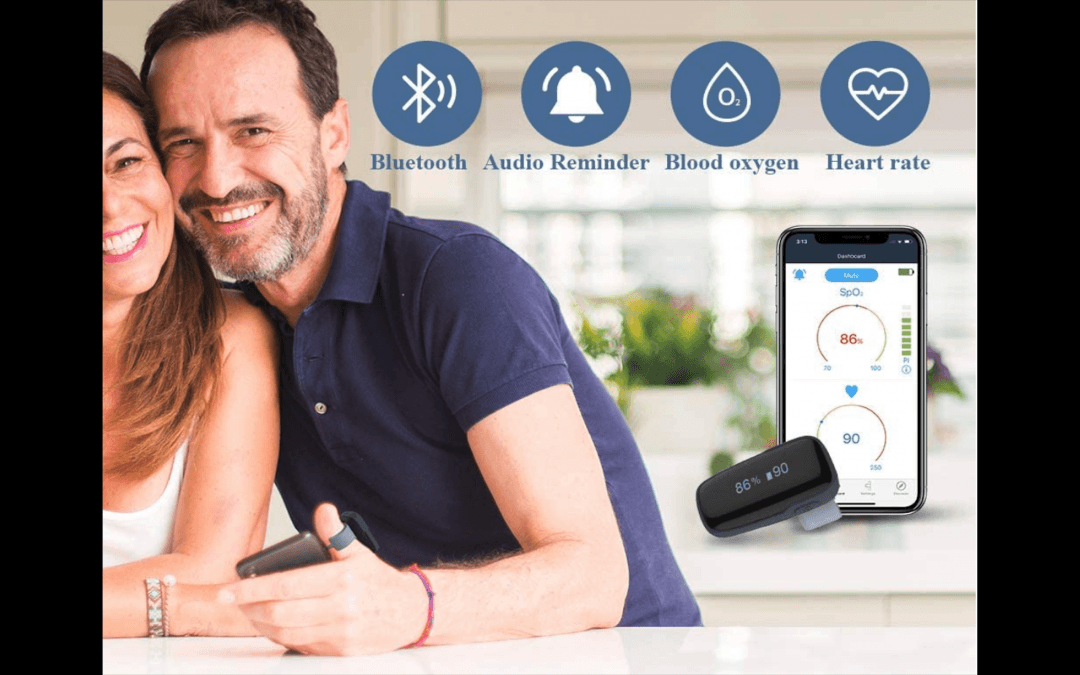

[It is interesting to note that the picture in the ad that I lifted from Amazon about a pulse oximeter that costs about $150, and can be delivered to your door in two days, shows potentially pathological readings while the man wearing the oximeter looks healthy, and is hugging his significant other. His O2 sat is 86, and his pulse rate is 90. If his respiratory rate on a WHOOP was 24, should we admit him even if his rapid C-19 test is negative? We are back to the same sort of clinical dilemma we have when a young person presents with a great story for ischemic heart disease associated with a few non diagnostic clinical abnormalities.]

No test is “diagnostic.” As Dr. Levitan notes, even the C-19 testing has a high “false negative ratio.” [In a previous post I had mentioned Paul Romer’s suggestions for screening at levels that would allow loosening up the economy. In part because of false negatives, his conclusion was that we needed to do 22 million tests a day!]

I do believe that the combination of tests also provide increased sensitivity. A combination of elevated temp, elevated respiratory rate, and even a slightly low O2 sat should be a sign of concern even if the C-19 test is negative. I agree that it would be great if symptomatic patients who are going home could have access to an oximeter.

What I do not know is whether we have enough oximeters to create a policy, or if we did could we organize there . use, and get people to agree to surveillance. Like respirators, masks, and other protective gear we [probably] would need to ramp up production.

I fear that there is a difference between what we “could do” and what we are likely to do, especially since we do not have any uniform leadership. At the practical level I think there is great benefit in individuals having this information, and my bet is that oximeter producers will see an increase in orders.

Dr. Levitan’s observations will improve care, but as much as I wish it were true, I do not think that it will enable a safer return to normal because the primary source of spread is likely through asymptomatic people who do not yet have temps, elevated respiratory rates, or falling O2 sats. I do agree that early intervention is likely to reduce morbidity, and improve mortality, but without a “penicillin” like certainty of treatment with antiviral therapies like we now have with AIDS or until we have developed a vaccine and immunized a majority of the population, I don’t think we will completely solve the problem…

…I am not so sure it follows that we can tolerate substantially higher levels of infection without overwhelming the healthcare system — hence substantially improving the trade-off between controlling the spread of the virus and enabling greater economic activity.

Is the objective “To not overwhelm the healthcare system and return to greater economic activity”? Or is it to preserve life and the economy?

…Patients with pneumonia who don’t require a ventilator still have very long hospital stays, serious complications and long periods of recovery. Protracted illness can be more expensive to society than many deaths. I think that there is no way of opening up the economy that is risk free…

…I think when we begin to talk about acceptable numbers of deaths we can tolerate to get back to business, we are walking close to an abyss. Remember when Sarah Palin and “the right” were able to mobilize voters over potential death panels with the ACA? Now those same voices are talking about acceptable mortality to save the economy. Paul Krugman has calculated that maintaining the limitations is more likely to be “less expensive” in terms of the macro economy than a resurgence of disease would be. [In a later piece he has said that the push to open the economy is coming from “cranks and cronies” and not from economists.] I don’t think we have the population control to open the economy. We have great abilities to rationalize why we should.

One thing that I have read is that to safely open the economy, even at the 80% level that Scott Gottlieb recommends, we will need a level of invasion of privacy that is likely to be politically impossible. [The role of compulsory monitoring and the associated privacy issues would be a long discuss.}

I don’t mean to imply that I think that your question is inappropriate. I am just venting yet another frustration with the president and his base. I see the question of when and how to return to a more “normal” economy as a major test of values, and our ability to take a long view. Of even greater concern to me is the fantasy that we can withdraw support from the WHO, ignore India, Africa and South America, and think that we will be safe.

I guess that some people buy a gun to feel safe. After this info about oximeters, I think I will buy an oximeter!

The second letter about “when” allows us to do something that helps us get through the moment. There is always great relief in thinking positively about the possibilities for the future. My friend and guru writes:

Gene,

….I am curious about your perspective on what the Top challenges HC leaders will face in a Post COVID world. Here are mine:

1) The telehealth care model will be here to stay – It took a pandemic to have CMS realize this is something we should have done years ago. President Trump hailed it at one of his many press briefings on 4/15. Not all the patients are coming back.

2) Re-connecting will be critical, especially for those with chronic diseases. We have been putting these visits off and people aren’t getting healthier in these times so their chronic diseases are likely deteriorating.

3) Cash, obviously, will be strained – Systems will want the elective surgeries, cash cows, back soon. How do we teach systems to schedule and operated their surgery centers more efficiently?

4) Multiple care pathways will be required. There will be new screening (not just triage) but screening of patients that I believe will be long lasting… Facility designs must change.

5) Physicians now, more than ever, face burnout due to working on/with the COIVD epidemic for so long. How do they catch their breath after? I think many will retire, accelerating the perceived shortage of physicians…

6) Supply chain – No longer will it be tolerated to rely so heavily on China for low cost drugs, PPE, and DME

Not sure they are prioritized, but very important… What say you? What would you add with your CEO hat on? What would keep you up at night if you were still CEO of Atrius? – PS – NO TIME TO RETIRE…WRITE MORE…..!!!!! What are your daily “press conference” notes/observations? Call it “For What It’s Worth”

Hope you are staying well.

Well as you might guess, I did “WRITE MORE” about these “when” related observations. It was a long response so here is some of what I wrote about “when.”

I think all your points are correct. To emphasize them we need to go upstream with leaders and policy makers, and talk about what the pandemic has revealed as unsustainable flaws in healthcare finance and delivery. To miss the opportunity to create a new normal would be a shame. You know the phrase: “Never waste a good crisis.” FFS makes the system into a revenue focused machine that is organized for volume, and thinks about selling services, rather than a care delivery focused system that is deployed to maintain and improve health and is able to respond to community based issues.

The COVID-19 disaster is very acute and dramatic, but it is not the only current failure of the FFS system. FFS has had a very poor response to the “diseases of despair”: suicide, alcoholism, and drug abuse. Chronic disease management is also best delivered from established programs that are poorly funded through FFS mechanisms. One fear that I have is that if we do get Medicare For All or Medicare For All Who Want It, the funding mechanisms will be FFS.

I know that as a consultant who must deal with “what is,” it’s not your job to change healthcare finance. Your job is to help your clients deal with the current system, but in a way that prepares them for what might come. What I always liked about what Lean taught was that it was applicable to any finance system. ThedaCare and Virginia Mason are FFS systems, and waste elimination through Lean worked for them.

I think that you are right that we will not go back to where we were on March 12. I do think that the processes you instill should be forward compatible with any potential change in system finance. Bundled payments and ACOs were steps in the right direction, but are built on a FFS chassis. In essence both were/are meant to be mechanisms to lower utilization despite the driving energy of FFS at their core which always trying to do more to make more at the individual doc level which undermines population based objectives, and is a major source of clinician burnout. The financial problems hospitals have experienced from the pandemic would not have been so great if they were compensated to care for a population.

I think the biggest advantage of the pandemic and the quarantine is to show that we need much less “bricks and mortar” to adequately care for patients. In Lean terms one category of waste is a building that sits empty and unused for over a hundred hours a week. Here is the math:

There are 168 hours in a week. The site is open from 8 to 8 five days and 20% of space is utilized for 12 hours on Saturday and Sunday that is 60 hours plus 20% utilization for 24 hours which is 4.8 hours. Essentially there is 65 hours of use in a week and over 100 hours of waste. That is an overestimate since we know that at any moment when the site is open there are many empty exam rooms and unused space. We add to that the inconvenience that we offer most of our service time when our patients are busy at their own work.

Another way we generated waste pre March 12 was with the one on one encounter. We tried to change the math of that with the shared medical appointments. Other industries have effective ways of “multiplying” their intellectual assets. Telehealth offers the opportunity to see more than one client at a time for many events associated with chronic disease management. The best chronic disease management is self management, but people need support to self manage. Much of my face to face time was used to transfer the information that allowed for self management. That can be done online with prepared material or in groups online. For example, I am doing pilates online with a mix of individual and group sessions. The group sessions are pre recorded, and I pay $20. The personal session is $80. Physical therapy can also be done online. My pilates is still FFS, but in a population health program where the product is a cost and not a revenue stream, there would be big benefit and big savings over standardized PT.

The missing factors that have limited innovation in care delivery have been funding and ways of overcoming the barrier of the status quo. People just keep doing what they always have done. Now, COVID-19 has prevented us from doing what we always have done. It has shown that a lot of care can be done online, and even better it can be done discontinuously. My group pilates class is recorded. I can do it anytime I want to. My individual sessions require an “appointment.”

There have been physician barriers to delivery innovation that have now been “cracked.” Doctors have had to do it. Patient reluctance has also been a barrier, but now patients have experience with online care. They were never as reluctant to get care online as doctors were to provide care online. The biggest reason it was not done was because there was no revenue line. Payers were reluctant to pay for care if it was not face to face. Kaiser was self funded and was able to turn over 25% of its work into “alternative touches.” I think that more than 50% is possible, and outcomes will possibly be better. I think that it is quite likely that healthcare finance will be a bear for a while. There have been huge system losses. There will be no finance gravy trains for the next several years.

I think that a key exercise is to decide those touches that must be physical encounters. It is also true that many of the physical encounters do not need to be done by physicians. If I were working with a client I would build the argument that whether payment is FFS or capitated, it is possible to reduce overhead from bricks and mortar and all of the associated human resources and costs for facility maintenance. Out of pocket patient costs could be reduced, and the cost of “going to the doctor” can be reduced. One huge future problem is the cost of personnel, docs and others, required to maintain the pre 3/12 system. We can better leverage our human resources with a good online care system.

The facilities that will be “freed up” can allow system expansion or allow physical sites to be repurposed in some way to capture savings. Many outpatient facilities for ambulatory care are leased. When HVMA was struggling in the early 2000s, we got rid of a lot of clinical space as we lost 100,000 patients.

After making the case for “not trying to go back,” and then determining necessary physical appointments, you are prepared to begin to think about how to efficiently go forward into the new model.

I have long felt that we overused both the hospital and the ambulatory environment. Cost is a barrier to universal coverage, but we are now proving that not covering everyone has even greater costs. It is ironic that many people who are “happy” with their employer provided care don’t use it because uncovered costs make it too expensive. Many systems were seeing a fall off of elective procedures and rising labor costs before 3/12. “Casual Lean” helped some systems a little, but it was clear to me that many smaller hospitals, especially rural ones, were beginning to get into trouble, and were losing more and more money on operations primarily because of lower utilization and higher labor costs, primarily nursing. Half of all admissions are for failures of ambulatory care. There is opportunity there.

I doubt this is what you were looking for, but using Lean thinking to direct efforts post 3/12 with a resolve to not go back to what was really not working well before, makes a lot of sense to me. I’ll keep thinking about it.

I hope that you are split in your thinking, spending some time contemplating how best to contend with “now” and dreaming about the possibilities of “when” we emerge from this harshly imposed group learning experience. I am delighted that there are people out there like my two old friends who are willing to advance ideas and engage in discussion of the best current and future possibilities. It is the dual focus of “now” and “when” thinking through our history that has made us great. Those are the same skills at an individual level that most care providers used to get through long hours and many years of training while many of their contemporaries were enjoying a day at the beach and letting tomorrow take care of itself. There is too much at stake at this moment in time to be cavalier about the return to business as usual, and it would just add to the enormous losses we have already experienced if we do not resolve to use what we have learned from our tribulations to fashion a new and better approach to health for everyone.