I have been trying unsuccessfully to give some attention to something other than the rising number of victims of the coronavirus. I analyze the progression of my intellectual and emotional responses to COVID-19 along a timeline that runs along the same track of the growing numbers of infections and deaths around the world as continuously documented by the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center.

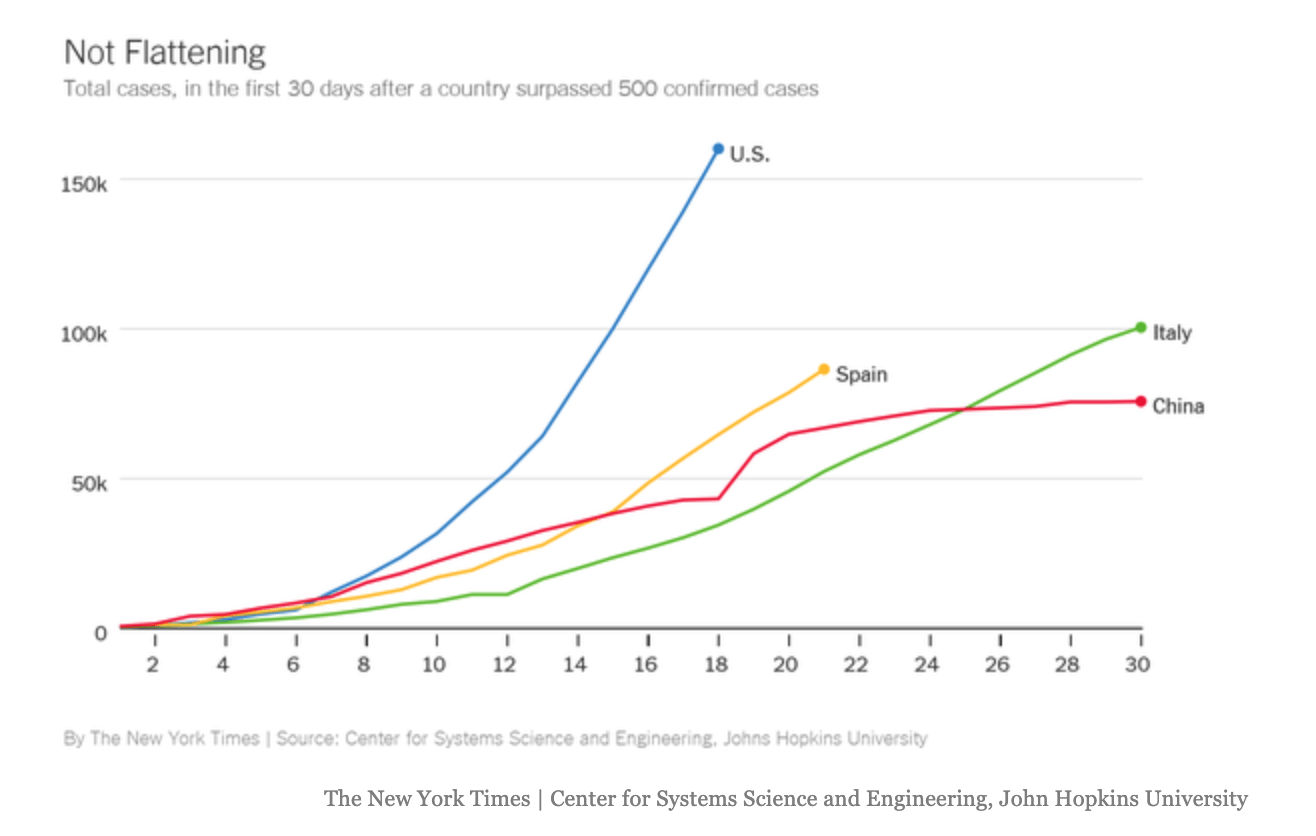

If you go to their database you will discover the number of cases documented in the moment. As I am writing to you a little after 8AM on March 31, there are over 800,000 cases documented world wide. There will be many more by the time you read these words. The number has doubled world wide over the last eight days as you can see by the little graph in the lower right quadrant. Here the virus is moving faster. David Leonhardt reported this morning in his New York Times newsletter that in America we have doubled the number of our cases in the last five days. In some places like New York, the doubling time has been much shorter, as short as every 2 to 3 days. Leonhardt’s graphics suggest that we are not “flattening the curve” as they did in China.

It is not a pretty picture. Is our poor performance attributable to our leadership? Did the president’s early unwillingness to accept the full extent of the threat doom us to a worse experience and more deaths? He writes:

President Trump spent almost two months denying that the virus was a serious problem and spreading incorrect information about it. Since then, he has oscillated between taking sensible measures and continuing to make false statements. (Yesterday, he said that hospital masks might be “going out the back door” — suggesting that doctors or somebody else were stealing the masks rather than using them.)

He points out that many of the governors are doing a much better job. Not all governors are the same though. The Boston Globe has published an article about the “red/blue” divide over the response to the virus by highlighting the difference between Bristol, Tennessee and Bristol, Virginia. Bristol is one of those towns like Texarkana where half of the town is in one state and the other half is in another state. Main street in Bristol is the state line. On March 21, on the Tennessee side of Main Street, where the governor is a Republican, the bars and restaurants were open. Everything was shuttered and all was quiet on the Virginia side of Main Street where the governor is a Democrat.

Does the virus know that in America all powers not explicitly given to the federal government are held by the state? If you live in Virginia that’s working for you. If you live in Tennessee, not so much. Seventy five percent of Americans live in states where the governor has ordered them to stay home. Twenty five percent live in states where some of the leaders and many of the citizens still believe the whole pandemic is a “hoax.” The virus may be spreading quite fast through those red states like Tennessee where the governor has been asleep at the wheel. I live in the “live free or die state” with an enlightened Republican governor who “gets it.” We have a stay home order. Maybe my governor’s wisdom flows from the fact that he was once an engineer and trusts science. As best I can tell, he is doing a good job, for which I am thankful.

The number of known cases at any moment that are reported is the number of positive tests done, and is not the actual number of infected people. As of now, it is unclear just how many people worldwide have been infected, but it would not be an exaggeration to imagine that the number is substantially more than a million. As you look at the numbers as they are reported by country and by state, it is amazing to discover that there are twice as many cases in the USA now as have been documented in China. The numbers vary a little from resource to resource. Johns Hopkins reports that there are infections in 178 countries and “regions.” The Kaiser Family Foundation is also keeping score and tracking the pandemic. Kaiser reports that 198 countries and territories have now reported one or more positive tests for the infection. The virus has made its way to distant islands in the South Pacific like Fiji and East Timor in the Indonesian archipelago. Close examination does show that so far there are relatively fewer cases in Africa and South America, as well as in many of the “red states” in the USA. These places remain as fertile ground for the future propagation of the virus.

We are told that in time there may be hundreds of millions of cases before the pandemic ends. I think that the fatality numbers are probably more accurate than the infection numbers. If you divide the 38,748 deaths known world wide by 801,400 positive tests, you get a 4.8% mortality. Since the mortality rate was estimated by Dr. Fauci to be around 1% (ten times the flu death rate) three weeks ago, expanding the case count to match the known deaths at a 1% mortality rate would suggest that there may be almost 5 million cases worldwide at this time. Using that reasoning, it is interesting to note that the 80,000 known cases in China produced about 3000 deaths which would suggest that they may have had 300,000 cases, if the whole population had been tested.

The raw numbers suggest that we have had twice the number of cases as China with the same number of deaths, 3000. Is that true? Is our care better, or is the difference in the accuracy of the denominator? So far our 160,000 cases here have produced about 3000 attributable deaths, which is about 1.9%, but if the death rate is really 1%, there is the possibility that we really have 300,000 cases. This weekend Dr. Fauci suggested that before the end comes, we may have between 100,000 and 200,000 American fatalities. If Fauci’s estimates of a 1% mortality turns out to be true, that suggests that before this is over we will have had 10,000,000 to 20,000,000 Americans become infected. That degree of spread will possibly achieve “herd immunity” at a very high price. Such math seems finally to have convinced the president, at least for the moment, that the storm will not pass by Easter and he has extended his social distancing guidance through April 30, at a minimum and perhaps longer. There are concerns that if numbers of new infections fall as the spring progresses, resulting in relaxation of the guidance to stay home as is now happening in China, we may see a “second wave come back in the fall.

As you study the numbers even more closely, you can see that for now the metropolitan areas have the highest numbers of cases and deaths. In my state the cases are greatest in the parts of the state where people travel to and from Massachusetts to work. The only county with no reported case of a coronavirus infection is Coos County. Coos is our northernmost county. It’s up on the Canadian border where there are more moose and deer than people. It is a red county in our purple state. The president got 52% of the vote there in 2016. New York and Boston may peak in the next few weeks, but we know our time will come.

I realize that I am “keeping score,” and I am not convinced that it is making me feel better. It’s been like watching an important game against a very challenging opponent. At first, I was approaching the whole thing as a curiosity that was at some distance from me. It was an idea that was hard to connect with at a personal emotional level even as it disrupted long laid plans for personal travel and long awaited family events. I was not that disturbed when the stock market lost a third of its value, which for a retiree living on a combination of social security and the required minimum distribution from a 401K should have been the source of great alarm. I tossed it off my fears by saying, “It will all come back when the virus is gone.”

I have spent a lot of time over the last three weeks yelling at the television during the president’s campaign style news conferences as he passes out misinformation, disagrees with his own experts, insults the governors who are trying hard to make up for the deficiencies of preparation that the mismanagement of the early days of the pandemic created, accuses healthcare workers of stealing supplies, and heaps contempt on honest reporters who are trying to ask the questions that we all want answered. I am past that now.

As I watched reports on television over the weekend, I noticed a change in what was being shown that says much more than the statistics and elicits more sadness than anger. I saw tired doctors and nurses asking for help and for much needed respirators, masks, and other supplies. I saw refrigerated 18 wheelers being “recruited” as morges. Yesterday, I saw a tent hospital being constructed in Central Park, and a hospital ship coming up the Hudson past the Statue of Liberty. I saw a priest in Italy blessing a convention sized gathering of people in caskets that were lined up in long rows in a warehouse.

I also saw happier things as well. There were many reports showing parents connecting with their children. Daughters were shown visiting with their elderly mothers in nursing homes on FaceTime, and when possible standing outside their mother’s window. My wife and I enjoy one or two “Duo calls” every day from our son and his two boys, ages five and two. We watch them run around and jump up on his back for rides. They live in California where they have now been confined at home for over two weeks. My son and our daughter in law take turns working on line and caring for their boys. The boys look wild, and the dad looks tired. They are lucky to live next door to a state park full of redwoods where they can go for midday hikes while getting close to nature, if not people. We are among the seventy five percent of Americans who are learning how to live in relative isolation.

In isolation, we attend meetings on Zoom and Skype, go church on line, and binge watch Netflix. I highly recommend Harlan Coben’s “Safe,” “The Five,” and the “Stranger.” If the tension of those thrillers gets to you, you can come back to earth watching “Virgin River” which is a sappy view of medical practice in a small town in the California Sierras, which was really filmed in British Columbia. One can not survive isolation without learning how to use Zoom. Without Zoom I could not continue my adventures with Pilates.

Today’s header is a screen shot of the wonderful and talented woman, Stephanie Singer, who has been my Pilates instructor for the last year and a half. Stephanie, a former ballet dancer, came to town about two years ago with her husband who is a teacher at a nearby high school, and their two sons. She is very entrepreneurial, and soon opened a Pilates studio that is neatly named Uniquity. I am missing dining out at local restaurants, and getting my hair cut, but because of Stephanie’s blend of innovation and commitment to her customers, my wife and I are getting “in home” telehealth continuation of our Pilates therapy over Zoom from Stephanie. What you see in the picture is what I see of Stephanie when we sign in to a group session of “mat Pilates.” This Thursday we will have our first “private” session where Stephanie will be watching us just as she did when we could go to her studio.

It is interesting to contemplate what will happen to our mat Pilates experience when the threat passes and we all resume social contact. I doubt that the world we re enter then will be the world we exited on March 13 after the markets fell, Tom Hanks got sick, the NBA cancelled its games, and the president woke up enough to reluctantly accept the obvious reality before he began to oscillate in and out of his uniquely confused form of ambivalence. When the virus passes, will Stephanie be a part of the healthcare world that will recognize the continuing opportunity that telehealth offers? I have stiff joints, old knee, hip, neck and shoulder injuries that were earned through many decades of self abuse, plus terrible posture. I am less stable these days when I walk around on icy roads or try to keep my balance in the fast moving current of a river full of slippery rocks while I cast my flies in hope of snagging a big trout.

I know that there are many seniors like me who could benefit from Stephanie’s skills and guidance if her online presence grew, and if Medicare offered her some compensation. I am sure there are many seniors with movement disorders like my wife who is fighting her early Parkinson’s disease who would avoid falls and could be more active with the help from online therapists like Stephanie. Is it possible that when life returns to normal, it will be a new and better normal?

Last Thursday David Brooks wrote a column entitled “The Moral Meaning of the Plague:The virus is a test. We have the freedom to respond.” He takes a very positive view of our isolation. He writes:

We’ll look back on this as one of the most meaningful periods of our lives.

Viktor Frankl, writing from the madness of the Holocaust, reminded us that we don’t get to choose our difficulties, but we do have the freedom to select our responses. Meaning, he argued, comes from three things: the work we offer in times of crisis, the love we give and our ability to display courage in the face of suffering. The menace may be subhuman or superhuman, but we all have the option of asserting our own dignity, even to the end.

I’d add one other source of meaning. It’s the story we tell about this moment. It’s the way we tie our moment of suffering to a larger narrative of redemption. It’s the way we then go out and stubbornly live out that story. The plague today is an invisible monster, but it gives birth to a better world.

I recommend the entire piece as inspirational, but should offer you one other snippet from it to read now because I do not want you to miss it’s wisdom. I bolded some important points.

Already there’s a shift of values coming to the world. We’re forced to be intentional about keeping up our human connections. Relationships get forged tighter by the pressure of mutual dread. Everybody hungers for tighter bonds and deeper care…

There’s a new action coming into the world, too. I was on a Zoom call this week with 3,000 college students hosted by the Veritas Forum. One question was on all their minds: What can I do right now?…

There’s a new introspection coming into the world, as well. Everybody I talk to these days seems eager to have deeper conversations and ask more fundamental questions:

Are you ready to die? If your lungs filled with fluid a week from Tuesday would you be content with the life you’ve lived?

What would you do if a loved one died? Do you know where your most trusted spiritual and relational resources lie?

What role do you play in this crisis? What is the specific way you are situated to serve?

We are all assigned the task of confronting our own fear. I don’t know about you, but I’ve had a pit of fear in my stomach since this started that hasn’t gone away. But gradually you discover that you have the resources to cope as you fight the fear with conversation and direct action. A stronger self emerges out of the death throes of the anxiety.

Suffering can be redemptive. We learn more about ourselves in these hard periods. The differences between red and blue don’t seem as acute on the gurneys of the E.R., but the inequality in the world seems more obscene when the difference between rich and poor is life or death.

So, yes, this is a meaningful moment…

What I have realized this week is that Brooks is right. I am more concerned about what will happen to others, and I am very concerned about family, friends, and myself. I do have a “pit of fear in my stomach.” Many of the people close to me are either immunocompromised from some chronic disorder or from their treatment for a cancer. Others are septuagenarians, like my wife and I, or even older. I am humbled as I have recognized my fears and the reality that I am not “brave enough” to answer the call for healthcare providers to come out of retirement to help the sick. That makes me feel very grateful for those who do have that kind of courage. I will try to do what I can in other ways.

Rahm Emanuel is credited with the quote, “We should never waste a crisis.” I am encouraged to discover that Emanuel’s wisdom is alive, and that there are many people who are using this crisis to contemplate what might be better in our “new world” when it comes. Perhaps we are now in the “gestation” of that new world as Brooks suggests when he writes:

The plague today is an invisible monster, but it gives birth to a better world.

It is better to anticipate the birth of something better than it is to focus on our continuing descent into the dystopian nightmare of greed and universal narcissism that seemed to be in the cards for us before the virus forced us to stop and contemplate the true meaning of our existence. I like the metaphor of standing in the doorway of a new world, a potentially better world with better healthcare as the leading edge of an effort to reverse the diseases of despair. We may emerge with a committed majority favoring the protection of the planet and a commitment to address and improve the social determinants of health. That enlightenment may arise from a new awareness of our connectedness on this small planet.

I got an email over the weekend from Paul Levy. Ten years ago when Paul was the CEO of the Beth Israel Medical Center and I was leading Arius Health and Harvard Vanguard, we discovered that we could collaborate in a way that could create value for the community. Now we live in different places, and don’t get to meet for breakfast and have conversations that ignite new ideas like we once enjoyed, but we do stay in touch with occasional emails. Paul wrote to me and a few other friends with a request:

I was invited to give a webinar on April 7 to a group of executives at a large university, and they asked me what COVID-related topic I wanted to cover. I told them that I was tired of stress and gloom talks and wanted to get people thinking positively about the future, so I gave them a title of “What do you miss the least from your workplace during the current crisis?”

My thought is to get them thinking about the wasteful, unproductive, and uncomfortable parts of their normal work routine and to think instead about redesigning work flows and routines, using what we would all call Lean principles.

I think this will be a lot of fun; but I wonder if you have any thoughts that you think would be helpful for me to use when I go through the discussion with them. Indeed, have you already seen examples from your clients or heard any good stories I could use?

Thanks in advance for your help!

I wrote back:

Paul,

I do think that there are opportunities in the aftermath of the trauma of COVID-19. The opportunities that interest me most fall into two broad opportunities related to the business systems of healthcare, and then there are the societal issues.

For years I have been fond of quoting Dean Ebert who said that to have a better system of care we did not need more money, more people, or better facilities to improve the health of the nation. We needed a better operating system and a better finance mechanism. His 60s experiment to test his hypothesis was capitation and a shift to more ambulatory care with a focus on prevention and health maintenance. Most people don’t realize that HCHP was an experiment to test his hypothesis.

He was right, but the market would not accept his product, and we have had fifty more years of FFS except for Kaiser. Read my last post. There is a link to a recent HBR article by Asch and Nicholson that points out that insurers are holding premiums that were generated in part to pay for the elective hips, knees, and hearts that provide more than the margin for most hospitals and practices. They will have a windfall from COVID because the billing is pretty slim on medical admissions, even to an ICU. The author’s solution was for the insurers to “give the money” to the hospitals. I assume that the mechanism would be to match some proportion of the revenues paid out to a given system on average over some number of previous years. In Massachusetts, Blue Cross has an attribution model. That would work also, but neither is likely to happen. What could happen going forward is that systems of care could demand payment for the care of a population. This is an event that reveals the stupidity of continuing FFS payment systems.

On the operating system side, continuous improvement mechanisms are clearly the infrastructure, but the delivery site is much more the “alternative touches” that are now required by social distancing. I tried for almost twenty years to move more care online. It is a ridiculous waste to maintain the millions of square feet of office space that Atrius, Partners, and BID/Lahey require to maintain a nineteenth century delivery system where nothing can happen until a patient walks through a turnstile. ( For years I used a slide that showed a turnstile).

The problem I had was that there was no compelling reason for the system to change. Those sorts of ideas were the reason that eventually led to my “retirement.” I finally decided that the system would not change no matter who was CEO until it ran out of gas. Well, now it has. Insurers are paying for telehealth! Atrius is closing half its sites which is what I would have done if I could have. Those facilities are not needed to deliver better care. The excess support and professional staff will be deployed to other activities. Coming out of this we should not go back to what delivered not so good outcomes at a high price.

On the social side, I think we will quickly realize that we are all more secure with investments in infrastructure and to improve the social determinants of health. For starters everybody is better off if everybody has access to care. That includes the undocumented population since viruses don’t check your citizenship. I am not against capitalism, but markets require customers and customers require money to spend, and money comes from paychecks to people who have a higher “compensity to consume.” It’s ridiculous to say that the capital gets invested and trickles down. Some money does get invested, but more needs to end up in paychecks. We are way out of balance. Will we use the enormous challenges of our economic recovery to bring better balance to the market?

Those are my off the cuff thoughts. You have a chance to be brilliant and I am sure you will be.

All the best,

Gene

As I re read my response to Paul, I have to admit it was a little radical. Since writing back to Paul, I have discovered that my old friend and colleague Dr. Zeev Neuwirth is making a much more positive effort using his podcast, Creating a New Healthcare, to envision how we might pass through the doorway from where we are into a better future. He is launching a series of broadcasts entitled, “How COVID-19 is Reframing Healthcare in America.” I have listened to the first two episodes and they are terrific. In his introduction to the series he writes:

As I observe the herculean efforts around me, I feel compelled to contribute and use my podcast platform to shed light on how this pandemic is accelerating the reframing of American healthcare… in real time. To that end, I am launching a limited podcast series entitled,‘How COVID-19 is Reframing Healthcare in America’. In this series, I reach out to interview future-facing healthcare leaders and entrepreneurs, and ask them two questions:

(1) How has the COVID-19 pandemic immediately changed the way you are delivering healthcare?

(2) How will COVID-19 reframe healthcare in America for years to come?

I am awed and inspired by the responses I’ve gotten in the interviews I’ve already begun recording for this series. I can’t wait to share them with you!

Perhaps Zeev should interview Stephanie. People like Zeev and Stephanie are not going to waste a crisis! They, and many of you who are risking your life every day to care for the millions who will get sick, and the hundreds of thousands who may die, are discovering that there is much that needs to change, and I am hoping that when the current restrictions are no longer needed, you will be prepared to lead us through that door to a new and better world. There is meaning in this moment. As Brooks says at the end of his piece:

Suffering can be redemptive. We learn more about ourselves in these hard periods. The differences between red and blue don’t seem as acute on the gurneys of the E.R., but the inequality in the world seems more obscene when the difference between rich and poor is life or death.

So, yes, this is a meaningful moment. And it is this very meaning that will inspire us and hold us together as things get worse. In situations like this, meaning is a vital medication for the soul.

Hi Gene. I agree on many fronts. Born in America but have been living in the UK for over half my life, it is so interesting, and somewhat disturbing how the different countries, not just the US and UK, but the rest of the world are already competing against each other over who is better at ‘saving the world’, or in Trumps case, who is ‘The Worst’! Where is the unity??

I must say I wasn’t a Pilates fan, but Self Isolating with my husband and cat, I knew I needed something to remove me from the sofa… (and my husband from the sofa, however he seems to be a bit more comfortable without me on it, sigh.)

Stephanie is not only an excellent Pilates instructor, she is also my sister. At this time when families are ripped apart, friends and partners separated by all that is happening in the world, I look forward to my 45 minutes a day of sister time. It’s also probably better that only one of us is doing the instructing… it might not be so fun otherwise. 🙂

Hey Gene, I always enjoy reading your posts, more so lately as they are a ray of informed sunshine in the midst of so much negativity and fear.

Looking for bright sides anywhere I can find them, for what it’s worth, well, having been to Paris years ago, I have always thought bidets were a better way to live, and for years I have been on a small campaign to get people to consider buying at least the little portable ones ($13) . . . since we cut down something like 27,000 trees each day to make the global TP supply, not to mention the costs of water and CO generation in the making of it. (And now there’s problem with systems clogged by substitutes like paper towels.)

I have had close to zero effect up to now, as it has been a largely taboo subject in the USA, but now on social media people are actually interested, and I have a moment in history where people are actually listening to one of my (many) weird ideas.

I grab my opportunities where I can find them 🙂

I do agree, I think a lot of people, esp. kids and young adults will come out of this with a broader perspective on life. Facing adversity has its advantages. “Toughens you up” as my father used to say.

We’ll get thru this, somehow. — jl

Hi Gene,

The search for meaning as we live through this time has been top of mind for me this past week. I find comfort in reading. I am currently reading four books in parallel, two of which are to help me in that search. I wonder whether your readers can recommend any others.

To help me cope with and better understand my fear of loss, loneliness, and death, a friend suggested I read Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal, which I have started and am learning from. Since early in that book Gawande mentions being affected by Tolstoy’s Death of Ivan Ilych, I’ve started to read that, too. It is startlingly simple and insightful, and it’s helping.

I’m also reading Erik Larson’s new book on Churchill and the Blitz called The Splendid and the Vile, which is making me grateful that even though we’re living with fear in this moment, we’re not living in the constant terror of bombs falling on us from the sky–that was not only a fear of what might be, it was a certainty. (As my beloved grandmother used to say, “Things could always be worse.”) Finally, I’m reading Robert Caro’s memoir, Working, on his research and writing process, which I find fascinating. After all, he wrote the Power Broker about Robert Moses and is working on the 5th volume and final volume of his biography of LBJ.

So, here’s my question: What are your readers reading now that they would recommend? Books that help in the search for meaning or perspective, or are just plain fun, engrossing, and impossible to put down?

Years ago I read two books that made me want to quit my job so I could stay home and just read them (which, of course, I didn’t do): 1) Bonfire of the Vanities, by Tom Wolfe, and 2) Lonesome Dove, by Larry McMurtry. Nothing to do with healthcare, but these days call for a diversion. I would recommend these books today to anyone. As the late chef Anthony Bourdain used to say, “Something good is good forever.”

Thanks for all you do, Gene. I hope to get some good suggestions!

Warm regards,

Eve