Is it just a small world where connections are closer than any of us imagine? Could it be that there are forces that we don’t yet understand that create connections? Perhaps there is nothing behind connections other than random chance.

All of those questions passed through my head last Friday afternoon less than an hour after the weekly “Healthcare Musings” was posted. The questions were precipitated by a remarkable response from Eve Shapiro. If you are a regular reader of these notes you probably recognize her name. Eve is the co author with Dr. Anthony DiGioia of the Patient Centered value System:Transforming Healthcare through Co-Design. I enthusiastically reviewed their book almost two years ago. Last year I asked you to contact Eve to help her with research she was doing in preparation for a book that she was writing about the joy of medical practice. In early July I reviewed some of the information that Eve had gathered for her book and had shared with me.

Eve and I have shared many thoughts on the Internet, but we have never met. Our conversations have always been about patient care and the joys and stresses of those who provide the care. I don’t think that we have ever shared any personal information. Until now alI that I knew about Eve was that she was an experienced medical writer. I have assumed that Eve might have gleaned a little bit about me from some of my notes that have an element of memoir. You might imagine my surprise when I got Eve’s comment about Friday’s post:

Gene,

First: what an amazing coincidence! I took two graduate school courses in literature from the same Jack Russell and he was by far THE best professor or teacher of any kind I’d ever had. As a writer I think of him almost daily, guided by his admonition, “If you fall in love with a phrase you’ve written, take it out.” Now that’s tough love but he was right! Reminds me of Coco Chanel’s saying, “Before you leave the house look in the mirror and take off one thing.” Weren’t we lucky to study with this man?! I still miss him.

Second: having interviewed more than 100 healthcare professionals for my forthcoming book, Joy in Medicine? What 100+ Healthcare Professionals Have to Say About Job Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction, Burnout, and Joy, I have come to believe we may be oversimplifying the causes of burnout and potential solutions. I also believe that repetition of a phrase (in this case, the Triple Aim) tends to rob it of its meaning. To this English major, anyway, clarity and specificity are preferable to the shorthand that a label can obscure.

As you might imagine we exchanged several emails about our shared professor. He was a remarkable man, and a great teacher who promoted critical thinking. He won teaching awards at the University of South Carolina when I knew him in the sixties, and he was one of the most respected professors in the English department at the University Maryland when Eve knew him many years later. I shared a story with Eve that I will share with you:

…One morning my clock radio goes off to get me up for work. I had set it to the radio, an NPR station, instead of to the buzzer. The radio comes on, and I am lying there in that half awake and half asleep state, and I suddenly realize that I am hearing Jack Russell. My first reaction is that I must be dreaming. Then I realize that I am awake. I realize that I am really listening to Dr.Russell just like I was in his class over twenty years before. He finishes speaking, and a woman asks him another question. By then I was awake and realize that I am listening to an interview. His book about his father had just been published and they are interviewing him on the radio. I assume this occurred in 1986 because that is when his book was published.

I had lost contact with him. I did not know then that he was at the University of Maryland. I bought the book. I always meant to contact him and thank him for all of his help and wisdom, but I did not. I kept putting it off. Another twenty years passed. One day in about 2008 while running with my daughter in law who is a reference librarian at UC Santa Cruz, I start talking about him, and how I wish that I had contacted him. She decided to look him up and discovered that he had died, but she did get me his last book. I put a link into the letter today to the forward of that book about narrative non fiction which was published about 2000 with the help of his colleagues after he had developed cognitive difficulties. It is clear from the forward just how much he was loved at Maryland. It was the same at South Carolina.

In that response to Eve I also commented on her second point when she said:

I have come to believe we may be oversimplifying the causes of burnout and potential solutions. I also believe that repetition of a phrase (in this case, the Triple Aim) tends to rob it of its meaning. To this English major, anyway, clarity and specificity are preferable to the shorthand that a label can obscure.

Dr Russell is a connection between us, but we are also connected by an interest in the stresses and joys of providing care. Her comments lead me to believe that we also shared an interest in the state of critical thinking in practice and in the organization and delivery of healthcare. My response to those ideas was:

I totally agree with you about labels becoming cliches that blunt discourse and thoughtful discussion. I was trying to say that when I said:

Has the Triple Aim become a cliché? Have we learned to repeat the six domains of quality and the Triple Aim like some piece of religious dogma that we can chant without living out its meaning?…

…The issues and conversations in healthcare are so diverse and so circular that I do believe that we need some organizing principles. The Democratic debates discourage me. Maybe it’s too early, but I wrote the same complaint in 2016. The press and the candidates never discussed issues in depth. Obama was professorial and did understand the Triple Aim. The ACA as proposed, not as passed, was a pretty good step toward its objectives.

How would you address my concern and avoid using cliche of the Triple Aim which I agree has lost its meaning? I guess that words that have lost their meaning is the definition of a cliché. To do so seems to me like trying to write about physics without E=MC2.

My concern that there has been a fall off of critical thinking in practice and in healthcare policy may just mean that I am an “old guy.” In fact on the Internet I frequently respond anonymously as “docoldman.” It is not uncommon for “retiring generations” to be sure that those who are taking their place “just don’t get it.” Eve pushed back:

I believe complacency in healthcare is as prevalent as complacency anywhere else: when we think we have the answers we stop asking questions. The field doesn’t advance and we remain stuck. Whether the topic is burnout–on which many consulting firms have been built–medical diagnoses or anything else, we need to keep asking and keep thinking. We should think like the students we once were, not the experts we believe we are.

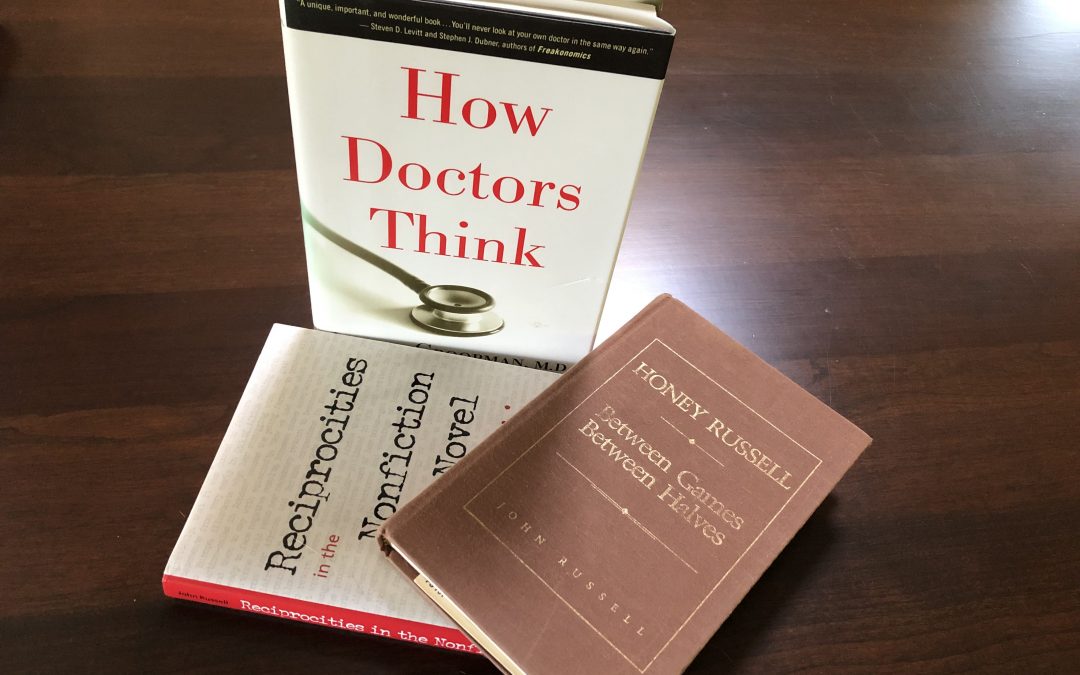

Have you read Jerome Groopman’s excellent book, How Doctors Think? He says that a big problem in making a diagnosis is relying on the diagnosis of the last doctor who saw your patient, and maybe on doctors before that. What docs should really do, he says, is to start over. Clean the slate. And make your own diagnosis based on your testing, your exam, your observations, and your own questions of and conversations with the patient. While there is value in looking back, basing your diagnosis on what others have determined doesn’t allow you to consider the same patient, the same conditions, the same symptoms with new eyes and to think differently. (He has a chapter called, ‘The Uncertainty of the Expert.’) Lives, he says, have been saved that way.

One of the reasons I tend not to like conferences is that presenters think they know everything. How refreshing it would be if presenters talked about uncertainties, complexities, doubts, and alternative ways of researching (qualitative vs. quantitative) that might provide different answers.

I know this is far afield from your discussion of the Triple Aim but I believe there is a connection. Any term loses its impact when we lose awareness of its actual meaning–what lies beneath the label–and revert to using, and overusing the term as shorthand for something that was once clear but has by now, through overuse, become amorphous. The term becomes rote–yes, cliche–and exploring, questioning, and thinking stop.

At this juncture two things happened. First, I felt that Eve and I were in total agreement about the reality that phrases or acronyms that began innocently as summaries of more complex thoughts ironically can become suppressors of the thought processes that are necessary to achieve their objective. We all employ mental “shortcuts” and summaries in our language that can decay into clichés that quickly lose their meaning for us and for those to whom we speak or write. In a way “cliché” is a cliché, “a phrase or opinion that is overused and betrays a lack of original thought.” As I implied in the post, it is easy to talk about the six domains of quality and the Triple Aim while doing nothing much to promote them:

Has the Triple Aim become a cliché? Have we learned to repeat the six domains of quality and the Triple Aim like some piece of religious dogma that we can chant without living out its meaning?…

The second thing that happened was that I reacted negatively to Eve’s recommendation of Dr. Groopman’s book. My response to her was:

Eve,

This is terrific. I do know [of, not personlly] Groopman and have even shared patients with him. I must admit that I have not read his books because of animosities that he has expressed about attempts to move toward some of the values of the Triple Aim. He and his wife Pam Hartzband, who is an endocrinologist, have co authored some reactionary pieces that have rubbed me the wrong way. That said, he is a brilliant writer and I probably should put my personal distaste for what I perceive his medical politics to be [out of the way] and get back to reading him…I know folks who think it is brilliant…His points about the approach to the individual patient are right on. I think we part over attitudes about a physician’s responsibility to the population and the cost of care. In Triple Aim terms, I think we agree on one leg of it, but perhaps I am misinformed…

I hit send and then immediately felt like a jerk. The truth was that I had admired Groopman’s writing in the New Yorker and had read one of his earlier books that had very good stories with excellent take away thoughts for patients and clinicians alike. I decided to take Eve’s suggestion. I would download the Audible edition of his book and listen to it on the walk that I was about to take. When I downloaded the book, the cover looked familiar. When I began to listen, I immediately knew that I had read what I was hearing. He begins with a case history involving Myron (Mike) Falchuk who was the Chief Resident at the Brigham when I was a Junior Resident in Medicine. As Dr. Groopman describes, Mike is an excellent gastroenterologist. Before I began my walk I searched my book shelves and there was the book. I bought it when it was first published in 2007. I remembered that I had disagreed with a comment early in the book that I saw as undermining evidence based medicine in favor of a return to the intuitive skills that I had respected but thought were overused and the origin of error.

As I read further, I realized that I had not “heard the message” in the book. Much of the book focuses on the sort of cognitive biases that Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky described, although he mentions them only once on page 64. The problem was that when I first tried to read the book I was biased against Groopman based on a sense from some of his earlier NEJM opinion pieces about the use of computers in healthcare, and the sense that I had that he opposed many practice innovations. All of that bias against him had been confirmed in my mind by the impact of the article that he wrote with his wife, endocrinologist Pamela Hartzband, in 2016 undermining Lean and continuous improvement science, “Medical Taylorism.” The affect that I expressed to Eve was more likely related to feelings residual to the Taylorism article than his earlier work, his New Yorker writing, or most of the NEJM articles written prior to the 2007 publication of How Doctors Think.

I realized even more about myself as I reread much of what I had previously read. In 2007 I did not have much background in behavioral economics and the biases associated with how we think that are described by Kahneman, Tversky, Thaler, Ariely, Sunstein, and others. I did not begin to read this literature until 2008 or 2009. I read Ariely’s 2008 book, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions, sometime after it came out in paperback, perhaps late 2009 or 2010. Ironically, it was a book that sported an endorsement by Groopman! Ironically, I made what Groopman describes as an affective error. I had rejected what he had to offer based on innuendo, other people’s opinions, and the superficial reading of some of his papers, one in particular, where he and his wife had jokingly claimed not to be luddites in a description of their “conservative” position cautioning us to be careful of computers. I guess that I assumed against a lot of evidence that they at least had some luddite tendencies because they were pushing back against “efficiency.”

We are not Luddites, opposed to all technological interventions; we can see that electronic medical records have many benefits. Mountains of paper are replaced by the computer screen, with rapid access to complete and organized information, with risks such as dangerous drug interactions automatically flagged. But we need to learn how to use this powerful tool in the way that is best for patient care, regardless of whether it’s the most “efficient” way.

As I ponder what Eve has revealed to me, I agree with her. Groopman’s book, How Doctors Think, is an important book. It underlines how we make errors, and that knowledge alone may ameliorate some of the misconceptions we have about the opinions of other people. “Failure to diagnose” is the most common reason for a malpractice complaint. If we are to pursue improved quality and safety in the attempt to improve the experience of care for the individual, we must help each other avoid defective reasoning by recognizing the biases that prevent us from getting to the right answer.

Groopman’s book came out at least three years before Kahneman wrote his masterpiece, Thinking Fast and Slow. [The link is to a column about the book by David Brooks.] That fact alone is remarkable to me because Groopman dramatically describes practice as a combination of fast and slow thinking which we know it is. We often must act by reflex when there is no time to ponder, but the are many times when we should be careful and deliberate as we draw pieces of information together and try to use them to construct answers to the questions and problems brought to us by patients. Groopman’s book suggests two important points to me that should be always on our minds as we go forward under all the stresses associated with healthcare. First we must be sure that we always create time for “slow” thinking when slow thinking is what the patient needs. Second, we must vigorously teach each clinician how biases impact their critical thinking.

It is interesting to ask whether or not inadequate time for “slow” thinking is a primary issue in the origin of burnout. It is also interesting to conceptualize the evolution of AI and other evolving “tools and touches” that attempt to “improve” care delivery not just in terms of the increasing number of patients we might see enabled by these tools, but rather in terms of how these tools might free us from mundane tasks in ways that will insure that we have more time for thinking “slow.” In retrospect, I owe Dr. Groopman an apology.

Dr. Russell taught critical thinking in the analysis of literature without the benefits of the vocabulary that we have learned from behavioral psychology/economics. I think that he was one of those rare individuals who naturally had those instincts. What was wonderful was that he wanted nothing more than to use good writing and literature to teach critical thinking. I think he realized his opportunity to pass those skills along. We need more teachers and mentors who can teach those skills to the next generation of clinicians, and then we must insure that we protect the time needed to do our slow thinking.

Eve, thanks for calling forth so many memories, and for helping me see how to use old lessons learned to point to a better future.