January is named for the two faced Roman god, Janus. One face looks forward in time, as one looks back assessing what has happened. Most of us adopt a “Janus” posture this time of year. At our holiday gatherings what has happened over the last year is a favorite conversational topic. With much less certainty we talk about what we expect will happen in the coming year. Journalists cash in telling us about all the great things we missed, the movies we did not see, the books we did not read, and the ideas that we did not ponder or appreciate in the flurry of the year we just survived. They make lists of the famous people who died and review the disasters that most of us survived. A few brave pundits give us prophecies of what to expect in the coming year. Most of us take in all this information and in quiet moments of contemplation, perhaps while sitting in traffic or waiting in a check out line, we begin to imagine and resolve what we will try to do to improve ourselves over the next year.

For as long as I can remember I have been an enthusiastic creator of New Year’s resolutions. Like most folks, I fail to achieve most of the objectives outlined by my resolutions, but Lean has taught me that the value of the exercise lies not in considering what you achieve, but in understanding how you failed. Among my friends who practice Lean I frequently hear the admonition that we manage what we measure. As I do a mental accounting of last year’s resolutions, I find that I failed on most of them but came closer to success or gave up less soon on the exercise whenever I used a method that usually included some form of keeping score. I am hoping that even for the projects that failed miserably using the Lean concept of hansei, or “deep reflection,” will enable more success this year. Hansei involves the Janus-like activity of looking back and looking forward. It is self reflection. Lean lives on collecting the objective measurements that confirm whether or not the solution to a problem or the work to improve a process was effective.

I failed to learn Spanish this year despite investing in an app called Babel. The lesson learned was that after you purchase the app you must invest a few minutes each day listening to it, and you are more likely to listen if you keep a diary of how often you listen and commit to some regularity. My guitar and piano skills did not increase as much this last year as I had hoped back on January 1, 2017. The truth is that I sat down at the keyboard much less than once a week, and rarely for more than 20 minutes. It was August before I even got the piano tuned. At the rate I am going I will be several hundred years old before I get in my 10,000 hours. Carnegie Hall is not in my future. I think the same solution might work for music that will work for Spanish, but Lean also teaches us not to start too many projects at once.

I did better with my exercise goals. With the help of a wetsuit to extend my effort into the fall, I swam almost every day between June and mid October. I did better with swimming than Spanish because I made a stronger commitment and prospectively scheduled when I would do it. I could have started sooner if I had found my wetsuit in May, but I did not locate where I had “stored” it before July, long after I needed it. Lean teaches us that everything should have a place and be returned to that place after use. It’s the sort of wisdom my mother tried to give me, but I ignored. If I had learned from my mom, or had more effectively applied Lean thinking in October of 2016 when I stored the wetsuit, I would have known where the suit was, and I would have been back to swimming in May when the water temp got into the mid fifties.

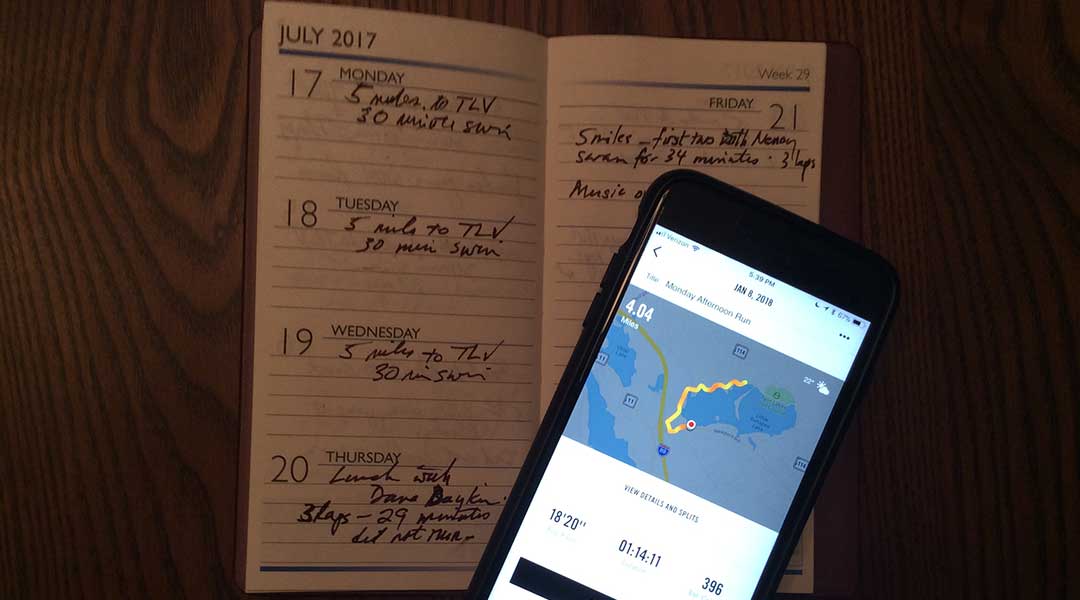

My best effort was my walking/jogging “mileage.” I wanted to do 1500 miles in 2017. I did 1,444. Just setting a goal makes it a game. I like games. My games have rules. Never miss more than two days without a walk or jog. Never go out for less than a four mile walk. Less than four miles isn’t worth the effort to put on your shoes. I usually log the effort in a dairy, and visually manage my progress toward the yearly goal with “countermeasures” when I get behind. That is Lean thinking also. In Lean we use “bowling charts” and “visual management” to stay on track toward objectives that cover long periods of time and use countermeasures to get back on track when the charts suggest that we are losing ground to the objective. When I apply hansei to my barely missed walking/ jogging goal several things come to mind as explanations for failing to reach my goal. First and probably most significant is that I did not write down what I had done every day, as I have in past years. I got sloppy and depended on Nike’s running app to “keep score.” As great as the app is, it does not have the same visual impact that my weekly log has. Now as I look at the whole year, asking myself why I failed, I can see that the major reason why I missed my goal was that I missed an inordinate number of walks while traveling, but did not do “makeups” as a countermeasures because I did not have the feedback from the app that I did from my diary based “bowling chart.” The data suggests that I need to be careful to get in a walk or jog everyday when I am traveling.

My experience this year reminds me that we manage what we measure and consider. I did a lot of measuring and not enough considering. My overarching goal for 2018 is to be more “aware” in all things. In my little self improvement games it translates into being more oriented toward focusing on the supports like metrics and visual management that are foundational for “considering” and the development of countermeasures, rather than abandoning my resolutions. I know from personal experience that applying hansei to my failed efforts at self improvement will improve my chances of having the success I desire in 2018, but that is of importance only to me.

The real issue at hand is how we will do as a nation in our recurrent resolution to improve healthcare in 2018. Did we learn enough in 2017 to make progress toward the Triple Aim in 2018? Since we are all limited by our personal “reach,” the important question is what you will be doing where you live and work. Will your efforts make a difference in your community and in your workplace? Will your community and your workplace be affected enough by what you do to become part of a larger effort that will make a difference at a regional level? Will the song you sing be loud enough and in the right key to join in a national choir demanding and contributing to an effective effort to move us down the road toward universal access, improved outcomes, and the effective use of resources that will carry us closer to the Triple Aim and sustainably improve the health of our nation? I hope so.

It has become somewhat of a cliche to say, “Hope is not a plan.” I could summarize all of the verbiage above by saying that failure coupled with reflection can foster resilience and improvement if there is a methodology that supports continuous improvement and a commitment to a purpose. There are a lot of indicators to suggest that when we sit by the fire on some snowy day next January and reflect on what happened and what we learned in 2018, we will feel like progress was made because individually we followed plans that made us part of a large national and even international movement that desired a safer, healthier, more equitable world for everyone. I think that it is prudent to point out that no one is safe, and no one’s health is assured, no matter what their wealth, as long as inequality exists in any of its many forms and as long as we allow our planet to be abused for short term benefits to a few. So what is your plan?

I will answer the question for myself since I can’t answer it for you. I plan to be active where I have the opportunity to make a difference. My wife and I can make a difference in our community by being active in the community programs of social action that exist. Some are sponsored by the ecumenical movement among the churches. Some are sponsored through civic organizations like nonprofits that provide recreational opportunities for youth or protect land and water resources through trusts and associations. Some, like the local VNA, the hospital, and local nonprofits to support women, children and families in crisis are involved with healthcare and education. We also plan to be active in the local and state election process supporting progressive candidates.

Lean thinking frequently gets to a statement of “if _ is done then_ will happen.” It is the hypothesis upon which improvements are tested and then revised in a continuous process of improvement. My “if” statement is quite long and I have put it in the form of a positive statement of “my personal plan to support hope.” It is as follows:

I will continue in board and foundation work in healthcare. I will continue to try to offer advice that supports the objectives of the Triple Aim to the for-profit companies that seek my advice. I will continue to focus on acquiring new knowledge that will aid myself and others in our collective journey toward a healthier world and the Triple Aim. I will share what I learn from reading, conversations and conferences through writing and opportunities to speak to individuals and groups. I will offer mentoring to anyone who requests it. I will endeavor to be open to the views and concerns of others, and by trying to understand the concerns of others, treat every statement of differing opinion with respect.

That’s my plan for hope. I am open to advise and ready for countermeasures if what follows my “if” is not a “then” of progress toward better health. I urge you to do the same.

We like to think we are good getting better. Last week’s letter and the companion SHC posting documented how poorly our country’s healthcare compares to other developed nations. The reality is that we are getting worse in the moment as judged by life expectancy at both birth and age sixty five. As always, men fare worse than women. This week David Blumenthal, President of the Commonwealth Fund, published a piece in Stat discussing the reality of our decline in an article entitled “Drop in U.S. life expectancy is an ‘indictment of the American health care system’. ” In the article he emphasizes, yet again, how our lack of universal coverage, our fragmented delivery system, our lack of progressive social programs, the behavior of our pharmaceutical industry, and who knows what other factors beyond the opioid crisis, are the cause of our deteriorating status in longevity. Do we need more notice as “A Reason For Action?”