It is surprising that we have no good metrics to track our progress toward the Triple Aim. We have lagging numbers on what we spend as a nation and debatable public health indicators of gross population metrics. No one knows how many healthcare organizations have incorporated the Triple Aim into their strategic plans. We have very little to help us judge what organizations are accomplishing and no way of comparing their results to those who are still ignoring the philosophy. In 2008 Berwick, Nolan and Whittington were remarkably honest and blunt when they suggested that very few organizations were pursuing the Triple Aim.

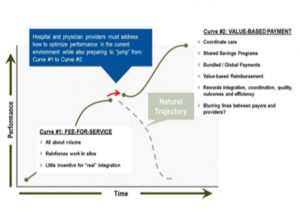

We don’t even know what percentage of healthcare organizations are striving to incorporate the six domain definition of quality from Crossing the Quality Chasm (2001) into their culture. It may seem harsh but my guess is that the large majority of healthcare is still focused on financial survival. As of April 2015 there were more than 500 ACOs in the country and there are surely more now. If all of them were aligned and making vigorous Triple Aim efforts it would still be a minority effort. That reasoning supports my impression that most organizations are still focused on finance and are “early on in their efforts” to make what has been called the transition from “Curve 1” to “Curve 2”.

“Curve 2” is consistent with the Triple Aim. The shift is necessary if we are to lower the cost of care but it is not the same as the Triple Aim. You can be on “Curve 2” and be focused on the transition to value-based reimbursement without embracing the responsibility of improving the health of the community or lowering the total cost of care.

The IHI continues to be the most beneficial source of insight for any organization that wants to be aligned with a Triple Aim vision. They have succinctly stated a strategic reason why every healthcare organization should be on a Triple Aim journey:

Importantly, stabilizing or reducing the per capita cost of care for populations will give businesses the opportunity to be more competitive, lessen the pressure on publicly funded health care budgets, and provide communities with more flexibility to invest in activities, such as schools and the lived environment, that increase the vitality and economic wellbeing of their inhabitants.

My concern is that there is an interdependence between assets in the community and the optimal health of the community that should require us to find the resources to make those investments now rather than after we have lowered the cost of care. What we see in the current world is the opposite. As our total infrastructure, public works, education, social services and cultural support further deteriorate, new medical concerns arise. Lead in the water of Flint, Michigan and the epidemic of opiate-related deaths are gross examples of deteriorating infrastructure adding avoidable tragedies to the cost of care.

Here is an interesting thought. Is healthcare less expensive in the other advanced economies because some of their success is related to the fact that they manage education, housing, employment, social services, and access to behavioral health resources better than we do? Could it be that their lower cost for higher quality care is a product of the fact that they are doing a better job of managing the social determinants of health?

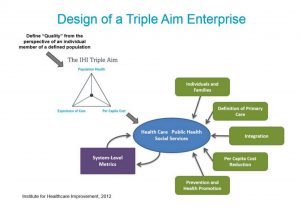

The diagram below was lifted from the IHI website and the article cited above. If you study the diagram you will see that concepts of quality as defined from the perspective of the individual as a part of a population is the starting point.

Unfortunately it seems that many of us only read the first part of this statement and that is where they are stuck. Do we see “Quality from the perspective of an individual…” and without noticing the last part of the statement: “individual member of a defined population?” Improving the care of the individual has always been like motherhood and apple pie but recognizing that every individual is a part of a population has not become the conceptual framework of the majority of providers and healthcare organizations.

Marc Hafer, CEO of Simpler Consulting (I am a Senior Advisor to Simpler) has suggested to me that for most people in healthcare the concept of “population” is not fully understood or appreciated. Processes of care that are efficient and effective for a defined population produce care that is more patient-centric, safe, timely, efficient, effective and equitable for every individual. It may seem paradoxical that if the population of which the individual patient is a member is better managed, the care of the individual improves. Most clinicians seem to see it the other way around. If they take very good care of individuals, they feel, the health of the population will improve, and they fear that if they focus on populations the care of the individual must decline.

Looking again at the diagram, in the blue oval we see Health Care, Public Health, and Social Services looking quite happy together. In the real world they are often three separate worlds that do not talk to one another. Within “Health Care” the fragmentation is even greater. The many silos within “Health Care” add complexity and compromise the care of populations.

I like the focus on system-level metrics suggested in the graphic, but to achieve the level of integration, quality improvement and the management of patients that impacts the achievement of the Triple Aim for everyone will also require metrics at the state and national levels. I was encouraged by the recent article by Porter and Lee in the NEJM that focuses on standardizing outcomes measurement. Nothing will facilitate the care of populations and the reduction of the total cost of care more than being able to compare real outcomes measurements and processes of care and the associated costs necessary to get the best outcomes.

After eight years of Triple Aim effort what was true in 2008 is still true in 2016. Our care is still the most expensive, least effective in overall quality, and has the poorest access of all the developed countries in the world. Ironically many Americans are convinced that their care is great and are threatened by any attempt to improve care for everyone. Most Americans have not heard of the Triple Aim.

The ACA has given millions access to healthcare, but with almost thirty million Americans still without care and tens of millions more who are “underinsured” with continuing costs that distort their economic security, we have a very tenuous hold on the first step to the Triple Aim. In Maine people are fond of saying, “You can’t get there from here!” Can we get to the Triple Aim from where we are now?

The one biggest thing that would enable the achievement of the Triple Aim would be to make access to equitable healthcare an “entitlement”. With a mandate you pay a fine if you do not acquire healthcare coverage. With an entitlement you can petition the courts if your healthcare coverage is inadequate. That is quite a difference.

National attention to the social determinants of health and to the resolution of “healthcare disparities” would be a great strategy. Until we make adequate investments in education, housing, support of cultural opportunities, and full employment, we will continue to swim against a strong current in our quest for the Triple Aim. Better measurement of outcomes would be a positive collective effort that would boost the Triple Aim.

Have you asked, “What part of the problem am I/are we?” Your part is the part you can quickly fix. Don Berwick advises us to think globally but act locally and internally where we can make a difference. At Atrius Health we realized that we could not change the world but we could advocate for change in our community and try to demonstrate that the Triple Aim was our strategy in pursuit of our mission. Our efforts were not as noteworthy as the efforts at Denver Health, Thedacare, Virginia Mason Medical Center, or Gundersen Health but we benefited from trying to mirror and learn from what we saw those organizations doing. Those organizations and others, many of which have become ACOs, are leading the way and are mapping their strategy from the principles of the Triple Aim.

In 2012 I attended an event in Washington sponsored by the IHI. The Triple Aim and the ACA were hot topics in the aftermath of the President’s decisive reelection and the judgement from the Supreme Court supporting all of the ACA except the Medicare expansion. One panel that day included Tom Nolan. He said that to improve healthcare in America three things were necessary: we must increase our efforts to adopt continuous improvement science, we must become masters of collaboration and the “commons”, and we must put what is best for our patients and our communities ahead of institutional and personal self interest.

As I look at the future and ask myself, “Will we ever get to the Triple Aim?” I want to answer, “Sure!”. But I am not sure. Earlier this year I wrote about the difference between optimism and hope. I am not optimistic about achieving the Triple Aim in the near future. There is just too much that still must change. I can hope that we are experiencing a “hockey stick evolution” and after a long period of preparing for change good things will suddenly occur at a geometric rate. Berwick, Nolan and Whittington told us in 2008 that the biggest barriers to the Triple Aim were the politics of the status quo and the difficulties of adaptive change.

My hope is sustained by the small numerator of organizations and committed healthcare professionals that I see who are make a difference in their communities and are providing examples of what “good looks like” for the rest of us. They are changing the status quo and are demonstrating that they can master change. I am hopeful because I know that no matter what percent of healthcare these Triple Aim organizations are, they are working hard and with urgency. I hope their efforts are moving us toward a tipping point. I am hopeful because many of these organizations have a Lean culture and know how to use Lean tools to manage “by process” across silos of self interest. I hear of innovations almost daily and some of these innovations may be a force of disintermediation that hastens the demise of the organizations that will never find the will or skill to survive.

One concrete reason I see for hope for the future is the growing dissatisfaction with the status quo demonstrated by millennials. Some or our older healthcare professionals are hoping to hang on a little longer and avoid change before they retire. If you are in healthcare and under forty, you should want changes that facilitates the Triple Aim sooner rather than later. Living and working in the last hours of one order is not nearly as exciting as living at the dawn of a new era.

The ideas and values of the Triple Aim will define the next era of healthcare. The alternative would be a dystopian reality that may sell movies and look exciting in video games but would be totally inconsistent with two thousand years of medical values that have always produced an urgency to look for better ways of providing care. The search continues in enough places that our knowledge of the destination is becoming clearer. It is not audacious to hope that one day we will have

Care better than we have ever seen, health better than we have ever known, cost we can all afford, …for every person, every time.