The Oscar nominations for 2020 were presented yesterday. Did the nominations match up with the list of recent films and performances that you thought were most noteworthy? As I looked at the list, and thought about the movies that I have seen, I realized that I am quickly losing touch with pop culture. Don’t get me wrong. I love the movies, and as you might imagine, I was delighted to see that Tom Hanks got a nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for his interpretation of Mr. Rogers. Maybe someday I might see “Joker,” but I have higher priorities. I am sort of tired of action flicks, gangster movies, and whatever it is that Quinton Tarentino makes. “Ordinary People (1980),” Robert Redford’s movie of a family in distress and the performances of Dustin Hoffman and Meryl Streep in “Kramer vs. Kramer (1979)” are all the dysfunctional family relationships I need to view on film. I have little interest in “Marriage Story.” After a careful review of all the nominations and the subsequent controversies, I want to nominate Terrence Malick’s “A Hidden Life” in a new category, the Best Thought Provoking Movie of 2020. Read on as I explain why I want to add this postscript to the very flawed Oscar process.

I admit that my idea is a reaction to my disappointment that as best I can determine “A Hidden Life” was totally left out of the nominations. I did find one article that suggested that it was so beautifully filmed that it deserved a nomination for cinematography. Sure, Malick’s movies are an acquired taste, and I must admit that when I first read about the movie in Richard Brody’s New Yorker review, I bought into the idea that this one was even more strange than his usual offering. I was not motivated to run out and try to see it. In the end, I saw it more by accident than intent. I am glad that happened, and some reviews, like the one written by A. O. Scott wrote in the New York TImes, do hear and see some of the unique message that Malick offers in this remarkable story. If you are not familiar with the movie, it is the true story of an Austrian farmer who tried to be a conscientious objector and refused to swear allegiance to Hitler and serve in the Nazi army. Brody almost gives a good plot summary:

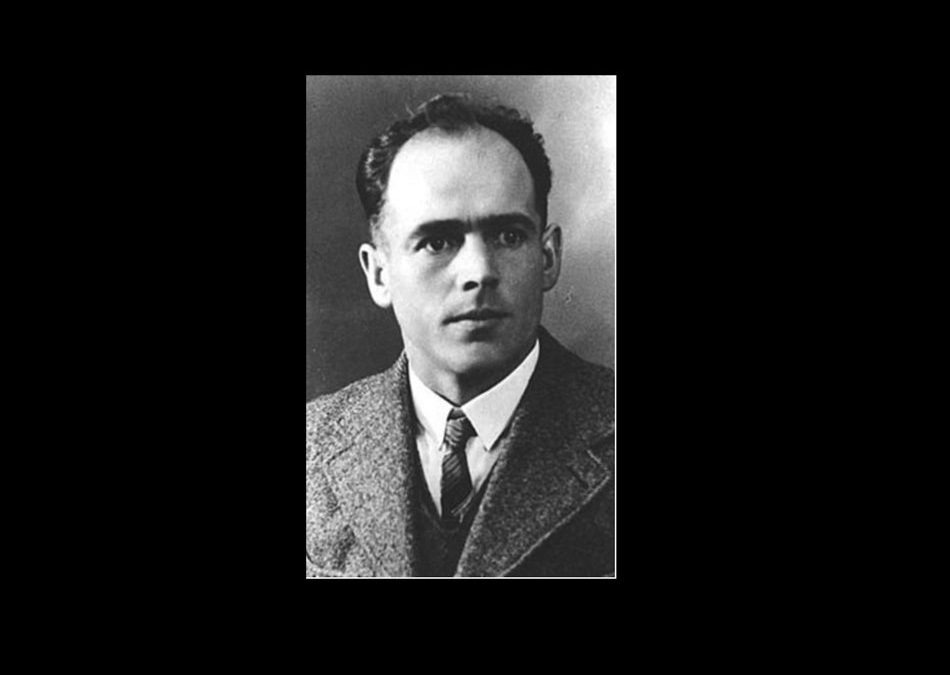

It’s based on the true story of Franz Jägerstätter (August Diehl), an Austrian farmer living peacefully in the rustic farm village of Radegund with his wife, Fani (Valerie Pachner), their three young daughters, her sister (Maria Simon), and his mother (Karin Neuhäuser). In 1940, he’s conscripted into the Army—at a time when Austrian soldiers, in the wake of the Anschluss, were forced to swear an oath of loyalty to Hitler. Franz doesn’t believe in the Nazi cause or agree with its racial hatreds. He thinks that Germany is waging an unjust war, and he doesn’t like Hitler. He shows up for military duty grudgingly but refuses to swear the oath, claiming conscientious-objector status, and is consequently arrested and imprisoned. Meanwhile, his outsider status—as other men in the village have gone off to fight and die—leads to Fani and their children being ostracized, apart from the secret support of a few friends who share Franz’s sympathies but not his resolve or courage.

Brody did not get the story line exactly right. Franz went through basic training and then went home for at least a year to await being called up for service. When he got the letter calling him to duty, he did report for duty with the slim hope of getting some alternative service as a conscientious objector. When he refused to take the oath of allegiance to Hitler he was arrested. The next three months were brutal. The depiction of his confinement was hard to witness even on film because you knew his horrible experience would end if he would just take the oath. We listen in agony to the letters between Franz and his wife that reveal his commitment to his principles, and his awareness that steadfastly defending his principles would cost him his life. In the end, he had a summary trial, was allowed to briefly see his wife, and then was beheaded.

That is where the movie ends, but not where the true life story ends. The letters between Franz and his wife were not lost. They became the source for a book, In Solitary Witness: The Life and Death of Franz Jägerstätter, written in 1964 by Gordon Zahn, a Catholic peace activist. Malick used the book and letters as references for his screenplay. Thomas Merton, the American Trappist monk who wrote one of the best selling books of the 1940s, The Seven Storey Mountain, promoted the story of Franz Jägerstätter by writing a chapter about him in one of his last books, Faith and Violence (1968). Ultimately Jägerstätter was named a martyr and beatified by Pope Benedict in 2007. Franziska Jägerstätter, his wife, who supported him in his difficult decision to stand on principle even when he was continuously advised that his sacrifice would make no difference, lived to be 100. She died in 2013.

I squirm during movies about real people trapped between what they believe is right and the cruelty of the world. Unfortunately there are many such stories. It’s an old, old plot line. Do you remember Daniel’s defiance that caused him to be thrown into the lion’s den? I managed my discomfort during the movie by trying to think about the deeper meaning of Jägerstätter’s decision, and whether or not there was a message for me in the story of his terrible dilemma, the choice between principles or death. My pain was intensified by the realization that the pain that would live on after his death, if he did not take the oath, in the sense of loss to be borne by his wife and daughters for as long as they lived. In the end he could not give up the feeling that it would be wrong for him to submit to the pressure of the Nazi war machine. He could not pledge allegiance, or even feign allegiance, for his life’s sake to what he considered to be a great evil, no matter what it cost him, and no matter that his sacrifice to principle would be known only to his family and to his neighbors, many of whom had already spat on him, and were sure that he was a fool.

As the film moved toward the relief that I anticipated when the drama would be finally over, I remembered the 1989 picture of the lone Chinese man, perhaps a student, standing in front of a tank in Tiananmen Square. I also thought about Nathan Hale, who professed to his hangman that his only sorrow was that he had but one life to give for his country. Franz, Daniel, the Chinese man, Nathan Hale, and numerous other patriots and martyrs have demonstrated that there have always been some among us who would stand on principle even when it might cost them their life and everything that the rest of us are so frightened that we might lose. I then began to think about my experience in medical practice, and I remembered the many individuals of all professional callings in healthcare that I have had the privilege of knowing who would, as a matter of principle, put their patients and their professional responsibilities ahead of almost everything else.

One of my greatest professional joys was our annual awards dinner. For many years I had the privilege of presiding over the event, although I never participated in deciding who would be nominated or chosen. I was always inspired by the stories that were told about the extraordinary acts of the individuals that we were honoring with awards. Almost every story was an example of circumstances that evolved in a way that required someone to make a choice between what was convenient or in their best interest or what was best for the patient or for our practice. True, no one ever sacrificed their life for what was best for the practice or that a patient might live, but there were many circumstances where the choice had a significant personal cost, and the acts were performed with no expectation of notice or reward.

I must admit that frequently I was embarrassed when I realized that the personal sacrifices we were honoring were necessitated by a variety of managerial or systems failures. On one occasion I facetiously suggested that we should call the evening the “Band-Aid” Awards because the events of professional commitment we were honoring had been necessitated as a bandage to compensate for those managerial or systems failures. Our professionals were willing to extend the strict interpretation of their “responsibilities” to cover needs that were caused by a failure that they had not caused that threatened the quality of the care we offered.

Franz was identified as a martyr. He was beatified by the Pope. Someday he may become a saint. I would suggest that those titles also belong to his wife, Franziska Jägerstätter, and perhaps also to his daughters. Franz’s pain was swiftly ended by the headsman. Franziska must have experienced some sense of pain and loss for the next seventy years of her very long life. His commitment cost his daughters the continuing presence and love of a father. Likewise, the sacrifices of the healthcare heroes we honored were also shared by their families and friends. They were often not home in time to see children before they went to bed, or were called away from long planned events, or had a weekend outing disrupted. No one is an island, and one person’s sacrifice often obligate others to an equal sacrifice or greater sacrifice that is rarely seen or acknowledged.

Some of the experts who have tried to provide understanding to the growing reality of professional burnout have pointed to the fact that in almost every healthcare organization we can identify people who are exhausted from being asked again and again to extend themselves because of a need that the system can’t quite cover. They see the extra patient who calls with a concern despite the fact that the schedule is “full.” They accept the responsibility of making an extra trip to the hospital to cover a colleague. They know the feeling of realizing that the appointment is not really over when as they start to leave the room the patient says that they have “one more question,” and they know that with the “one more question” the appointment really just started. The patient needed the previous half hour to work up the courage to ask “the real question.”

The demands that test character and commitment beyond reasonable expectations are not limited to the doctors and nurses in the office and the hospital. I know of IT professionals who have worked all night so that a system can “go live” when it was promised, or be “back on line” when the next day starts. I remember a thirty year veteran building maintenance man who decided to rise at 3 AM to come in to clear a parking lot of snow because he knew that we were short staffed because his colleague was out sick. I remember managerial staff working hard day and night to meet the deadline for an application for a federal program that was almost missed because of an error in communication. It is the rare person in healthcare in any position who can successfully avoid a call of duty that asks them to go the extra mile. At times it can feel like without professionals who are willing to be “Band-Aids” everything would collapse.

Perhaps it is a sacrilege to compare the commitment to principle that Franz Jägerstätter made to the acts of kindness and commitment that enables our flawed systems of care to try to make a difference for people who have sudden and unexpected needs that don’t occur during banker’s hours or that reveal a flaw in our system of care that must be rectified by a personal sacrifice. But, I think not. Malick added to my argument. When the screen faded to black to close the story, a quote from George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) appeared on the screen.

The growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

We owe a lot to people like Franz, but we also owe so much to those who rise to a challenge everyday that is often unobserved and frequently goes unnoticed. Those actions come from people of commitment and principle who put so much before what appears to be in their own best interest. Everyday healthcare professionals perform acts of unselfish “good” that we frequently take for granted or overlook, but yet we depend upon their generosity and commitment. Those “hidden” acts and sacrifices in ordinary or “hidden” lives still grow the good in the world everyday.